North America’s electricity sector is in the throes of dramatic transformation, and this is creating a bounty of opportunity for Aboriginal communities across Canada looking to tap the country’s renewable energy potential.

Three mega-forces are driving the change. Antiquated power plants, many built in the 1970s or earlier, are past their prime and must be mothballed. The environmental impacts of coal-based generation have also prompted regulatory changes that place greater value on cleaner sources of energy. And finally, a rising proportion of power authorities—not to mention industrial, commercial and residential consumers—are prepared to pay a higher price for non-polluting power.

The result is that a new electricity playing field has emerged and new players are entering the game. Canada’s First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities are among them, and it’s a game they’re poised to play well—and potentially dominate.

They have one advantage others don’t have. A high percentage of potential green power development is located on Crown lands, owned by the federal, provincial or territorial governments. Much of it is land that has been used by Canada’s indigenous people for generations to support their traditional way of life.

Supreme Court rulings, government policy and public expectation have reinforced the principle that resource development on traditional territory requires a duty to consult with local stakeholders. First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities are understandably protecting their turf, making strong claims that the development of renewable energy on their territory can only be possible through Aboriginal participation and ownership.

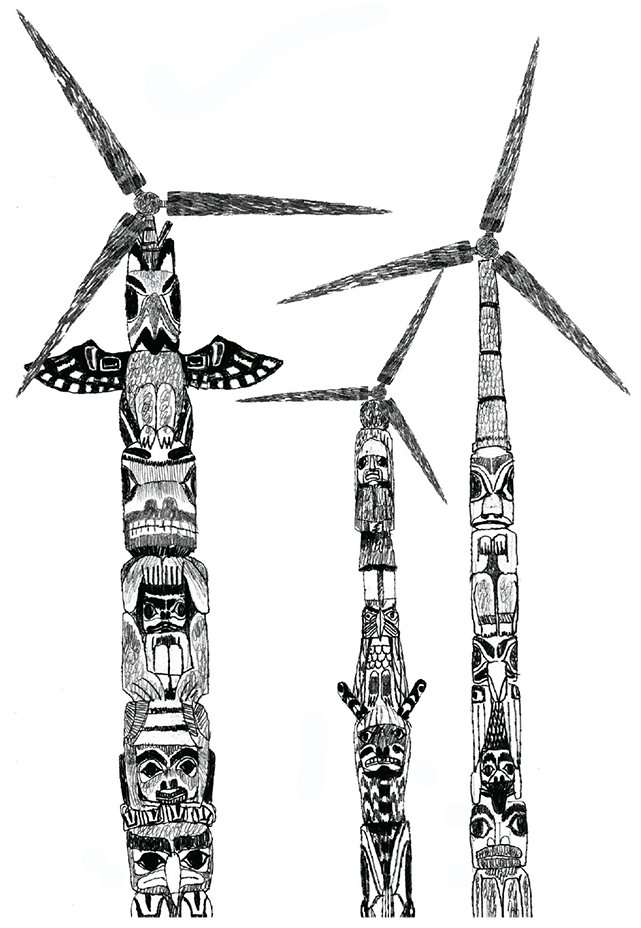

This should not come as a surprise. Native peoples have historically embraced renewable energy business opportunities. The notion of using the gifts of Mother Earth as a source of power is deeply woven into the cultures of the First Peoples of Canada. Simply put, hydro, solar, biomass, earth or wind power are cultural “fits” with Aboriginal communities seeking to build a sustainable and prosperous future. Not to suggest they want to pursue this opportunity alone. There is a squad of strong businesses ready to team up, and already we’re seeing utilities such as Ontario Power Generation and power development firms such as Alterra Power Corp. becoming willing development and financial partners with First Nations and Métis communities.

The score is rising fast. At the beginning of 2010, some 20 Aboriginal communities across the country owned a portion of clean energy facilities. By the end of that year an additional 24 Aboriginal clean energy projects had been approved. These projects are located mostly in Ontario and British Columbia, but action is Canada-wide and the trend is gathering momentum.

The Dokis First Nation, for example, has developed the Okikendawt Hydroelectric Project on Ontario’s French River with partner Hydromega of Québec. The 10-megawatt small hydro facility is a smart sustainability venture using existing infrastructure, and it avoids the use of new dams. About to begin construction, the project has been widely praised for its inclusion of heritage factors, such as the re-building of the historical Chaudiere portage trail, and environmental species protection. Okikendawt Hydro is among over a hundred small- and medium-sized Aboriginal clean energy projects in the pipeline from coast to coast.

The real game changer, however, is the roughly 20 large-scale hydro and wind power projects on the play list. All of these projects are either slated for development by their respective provincial government or under active consideration. These are huge initiatives, requiring tens of billions of dollars of investment. All are on traditional Aboriginal territory and will require the agreement of First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities to proceed.

One of those communities is the James Smith First Nation in Saskatchewan. Working with partners Brookfield Renewable Power and Peter Kiewit Sons, it is seeking to develop the 200-megawatt Pehonan hydroelectric project on the Saskatchewan River, east of Prince Albert. The project requires provincial and federal approval, and Crown utility SaskPower plays a major decision-making role.

Wind projects on the docket include Henvey Inlet in Ontario and the NaiKun project in Haida Gwaii, B.C. Ideal sites for both wind and hydro development on a large scale dot the Canadian landscape. My firm Lumos Energy estimates that the total installed capacity from the top 20 large hydro and wind projects to be developed will amount to an additional 13,000 megawatts and require an investment of $50-$60 billion. That’s roughly equal to about a third of Ontario’s current peak electricity demand.

Will all these large hydro and wind projects be fully realized? It’s highly unlikely, though most of them are on track. They just need to overcome major hurdles, such as obtaining all necessary environmental permits and getting access to and building new high-voltage transmission corridors. Another major challenge will be to ensure deals are structured so that Aboriginal communities, as project partners, get fair and equitable terms.

The economic upside is huge when considering the required infrastructure investment, job creation potential and cost-competitive power this will bring over the long term. There are also the environmental benefits of adding more renewable power to the electricity system.

Of crucial importance to the Canadian economy is that a large proportion of power to be generated from these large hydro and wind projects is targeted for export to the United States. Indeed, provinces like Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick, Québec, Manitoba and B.C. plan to build part of their future economic foundation on clean energy exports to New England and the West Coast States. Even Ontario envisions a more robust power-exporting future as larger projects come online.

It is power the U.S. will inevitably need. Power utilities and consumers there face stark choices. One; they can refurbish older coal plants with large capital investments, including expensive emissions control systems. Two; they can build new co-generation infrastructure which, while a viable option given the current low price and abundance of natural gas, is environmentally dodgy if it depends heavily on the development of shale-gas resources. Three; they can adopt a more diversified approach to meeting future electricity demand by blending capital investment in modern generating capacity with longterm contracts to import renewable electricity from Canada.

The third option may have the strongest appeal. It lessens capital investment demands and reduces risk exposure that comes with an overreliance on volatile fossil fuel prices. Moreover, large-scale renewable energy projects, especially major hydro sites, have proven to be an effective means of keeping electricity prices low over the long term. Provinces with the highest percentage of large hydro in their electricity mix, notably Québec, Manitoba and B.C., have the lowest retail electricity prices in North America. In addition, these imports will help states comply with increasingly strict airpollution regulations and future caps on carbon emissions. For this reason, power authorities across Canada are exploring ways to increase electricity exports to the U.S. based on large renewable energy projects developed in partnership with Aboriginal communities.

The role Aboriginal communities are poised to play in the future of clean energy development in Canada is undeniable, and it will become increasingly visible. For all involved, it represents a win-win-win proposition—for Canada’s First Peoples, for the economy and for the environment.