The world needs to double down on clean energy investments, not back away.

That is the conclusion of a report released in June by the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA), which, after three decades of being a fossil-fuel booster, has in recent years become a more vocal advocate for climate-friendly energy sources.

If there’s any chance of keeping the average rise in global temperatures to below 2°C, spending on clean energy development and deployment has to rise dramatically this decade, it argues.

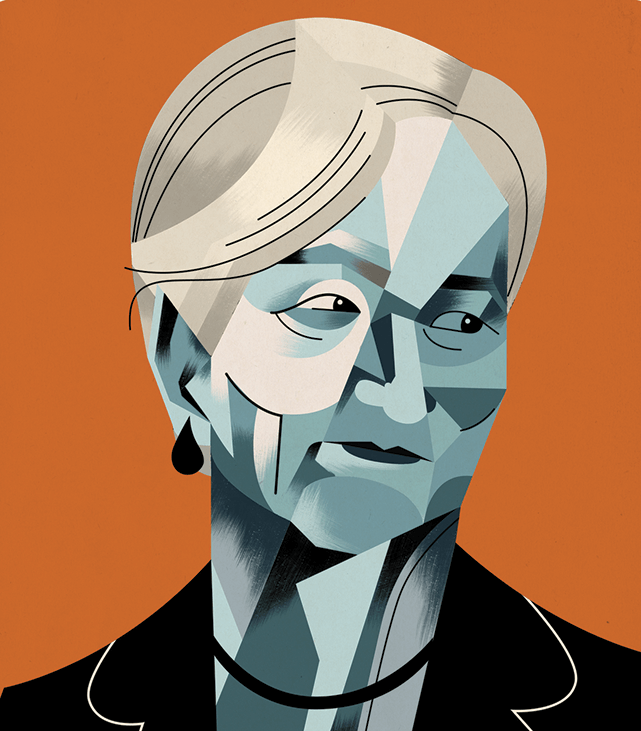

Between now and 2050, the agency figures $100 trillion (U.S.) will be needed just to keep the global energy system in working order. On top of that, $36 trillion needs to be spent on low-carbon technologies and energy efficiency. But Maria van der Hoeven, executive director of the IEA, has emphasized that the investment will pay off. Every dollar invested has the potential to generate three dollars in future savings, she says.

It may be a hard sell coming from an agency historically viewed as being in the pockets of the oil industry, but the IEA – precisely because of its conservative tradition – also brings credibility to the discussion. That the agency is now a champion of carbon pricing, the elimination of subsidies on fossil fuels and the responsible use of natural gas to displace coal, and is calling for a must faster transition to renewables, is a testament to the climate crisis we face.

Van der Hoeven, a Dutch politician, took over from previous executive director Nobuo Tanaka in September 2011. Corporate Knights had a chance to sit down with the former Dutch minister of economic affairs during a multi-stop visit to North America. Below are some edited highlights from that chat:

CK: You and many others have called natural gas an important bridge to renewables. Are you concerned how abundant, low-cost natural gas, thanks to innovations around shale gas development, is extending the length of that bridge and threatening investment in and deployment of renewables?

VAN DER HOEVEN: In two or three decades there will be nine billion people (worldwide) and that shows that the demand for energy will be growing, even with energy efficiency. We’ll need everything. To see to it that we go to a cleaner future, to renewables, we have to find that bridge, and that bridge is natural gas. Then we can phase out coal. The question is, how can we see to it that there will be a market for renewables? That’s exactly why I emphasize investments in clean energy technology, while also seeing to it that feed-in tariffs act to promote a more mature market for renewables. But there is something else endangering the whole thing. People are opposing the wind farms. They are opposing hydro. They are opposing geothermal. They are opposing solar. If you oppose that, and you oppose gas, what do you think the solution will be to provide these nine billion people with energy?

CK: Obviously, we’ll end up turning to coal. But are you saying our NIMBYism around renewables is partly to blame for how much we depend on natural gas?

VAN DER HOEVEN: It was mentioned to me, in this (northeast) region, that the lakes are a huge source of renewable energy. But the moment that people are opposed to using it, then the bridge we were talking about just now, about natural gas, will only be lengthened. So the answer to your question is a little bit complicated – it’s not only about gas, it’s about people’s acceptance of the generation of renewable energy on a larger scale than just panels on their rooftops.

CK: Do you think the transition to clean energy will be different in developing and developed countries? Will strategies vary in regions experiencing different paces of development?

VAN DER HOEVEN: I don’t know. Wind is coming of age in South America, for instance, and solar is being used on a large scale in a number of African countries. They are using these new technologies already in quite a professional way. Of course, when we talk about energy poverty, we are talking about those countries trying to catch up with already developed countries. What we also see is that the largest amount of energy demand will be exactly in these emerging countries, with China ahead of everybody.

CK: After a report the IEA released earlier this year, you called the current investment level in clean technologies insufficient. Isn’t it fair to say we’ve also experienced strong growth – indeed, record levels of investment over the past few years?

VAN DER HOEVEN: I agree. This is a very important conclusion. There are quite a number of people saying, “Oh, it’s not growing at all.” But it’s growing at a rapid pace. It’s just not enough.

CK: So what’s the solution? How can we tap into the capital required to make it enough? Is the IEA working on ways to tap into or unlock that private-sector capital?

VAN DER HOEVEN: The most important thing is for countries to develop a predictable and stable investment climate. That is up to them. We are not an investment agency, we are not a bank, and we are not the World Bank. We are policy advisors to our government members. But I think this is the most important thing they can do, because if there is not a stable long-term investment climate in a country, investment will not happen. People want a certain return on investment.

CK: Do you have concerns about the ability to move toward a low-carbon economy, given the economic issues we’re seeing in Europe and the United States? There are some economists who suggest spikes in oil prices are tied to recession and that every time we climb out of recession and get into a growth phase, it drives up oil prices and we get caught in this cycle of little recessions and growth spurts.

VAN DER HOEVEN: I don’t know if that’s the case, since the past few years we were in a recession and prices still went up, up, up.

CK: Isn’t the fear that they will go up even further if we see rapid economic growth, and that this will thrust economies back into recession?

VAN DER HOEVEN: Yes, but at this moment we don’t see rapid growth, we predict growth at 3.5 per cent a year. When we translate that into oil terms, we get 0.8 million (more) barrels a day. We are not going to translate that into prices. That is always unpredictable. But we can see at the moment that all prices are high, and that there is more interest in renewable energy. There are also some examples of countries that have invested in renewable energy and come out of the economic crisis better than others. That has to do with the employment. So it pays off.

CK: The IEA, a traditionally conservative agency born in the 1970s to protect global oil supply, has been noticeably more vocal on climate change issues over the past few years. Indeed, your chief economist has made several strong statements about the need to transition away from fossil fuels, or else. What’s behind that noticeable change in posture?

VAN DER HOEVEN: The reason we were brought to life in 1974 was energy security. And in those days, it was all about oil. But energy security in 2012 is about sustainability, affordability and accessibility. And that brings climate into the story. It’s important that an organization like IEA realizes there is a strong link between economy, environment and energy. They really influence each other. And the moment that you forget about that, I think you’re not doing the right job.

CK: But it is an evolution of the agency’s position, yes? Environment was never previously a key pillar of concern.

VAN DER HOEVEN: Energy security is the key pillar, of course, but there are other pillars underneath and one of the pillars is technology and one of the pillars is the influence on climate. Of course, there is an influence of energy on climate because of carbon dioxide emissions, but we also have to look at how climate influences energy security. What about Hurricane Katrina, for instance? Or droughts? This is something on our minds. That is why our mission statement is affordable, accessible, sustainable energy security – for all.