“Running bitcoin,” tweeted cryptocurrency pioneer Hal Finney in January 2009. A few days later, he received the first 10 Bitcoins ever traded. Finney loved the idea of a secure, anonymous digital token free of national controls. But two weeks later he returned to Twitter to warn of a bug in the system: “Thinking about how to reduce CO2 emissions from a widespread Bitcoin implementation.”

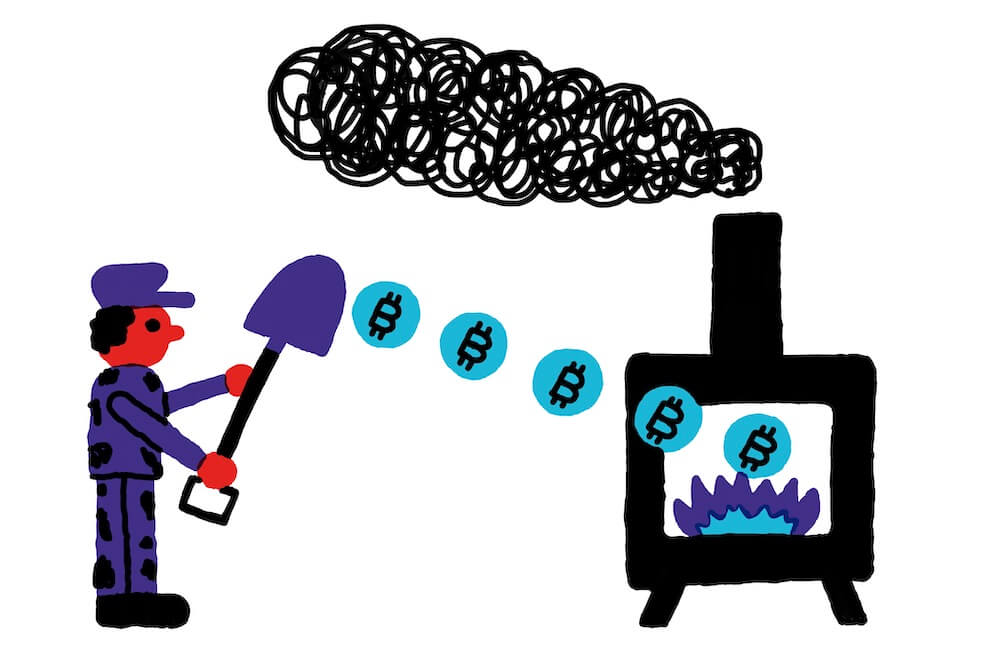

Twelve years later, the world is coming to grips with the eco-disaster that is Bitcoin. The currency backstops an alternative global payment system, with the value of a single Bitcoin hitting $79,000 in mid-April, up from $10,000 in January 2020. But Bitcoins are intangible units of value created by networks of supercomputers, and the environmental impact of running these machines equals the carbon footprint of a mid-range industrialized country.

Many of these server farms are located in colder countries to save energy, and some, as in Iceland, Norway and Quebec, use renewable thermal and hydro power. But according to the University of Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), two-thirds of Bitcoin power is generated from fossil fuels. About 75% of Bitcoin mining occurs in China, which derives 65% of its electricity from coal. (In May, ironically, China banned the country’s payment companies from handling Bitcoin transactions; its central bank dismissed virtual currency as “not a real currency.”)

Real or not, Bitcoin eats electricity. This became clear in mid-April when a coal mine flooded in Xinjiang territory, in China’s remote northwest. When the mine closed for safety inspections, the disruption to regional power plants briefly shut down a full third of Bitcoin’s global computing power. Suddenly, Bitcoin’s yearlong price run-up came to an end.

The CCAF estimates Bitcoin production will consume about 130 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity this year – about the same as Argentina, the Netherlands or the province of Ontario. That’s a big jump from 2019, when the CCAF calculated that Bitcoin production burned 45 TWh.

And demand is expected to grow. As more miners set their caps for Bitcoin, the algorithms required to earn a Bitcoin become more complex, requiring ever more computing power.

The backlash has begun. In a bid to reduce its carbon emissions, China’s Inner Mongolia region is trying to shut down unauthorized Bitcoin miners. In May, Tesla founder Elon Musk tweeted that while he supports the notion of cryptocurrency, Bitcoin’s “energy usage trend over past [sic] few months is insane.” He said Tesla would stop accepting Bitcoin payments until the industry “transitions to more sustainable energy.” Analysts claimed Musk’s decision would send a strong signal to other firms.

Some Bitcoin miners are fighting back. They’ve signed a “Crypto Climate Accord” that proposes to decarbonize the crypto industry by making it 100% renewably powered by 2025. But that may not be enough to prevent Bitcoin from becoming a stranded asset – like existing coal mines and oil fields that society can no longer afford to operate.

Ben Ashby, a partner with London-based Good Governance Capital, says Bitcoin’s dependence on computer processing makes it a fossil itself. In addition, he says, Bitcoin’s decentralized nature defies ESG investors’ attempts to conduct environmental audits. Ashby believes investors will increasingly shun Bitcoin in favour of more sustainable solutions: “There is no intrinsic reason why this mining activity has to happen.”

With governments developing their own digital currencies, Ashby says Bitcoin’s fate may be to go down in history with MySpace and Betamax – as experiments that seemed like a good idea at the time.