(Yesterday, we looked at how the oil sands evolved from a money-losing proposition to a lure for international investment and a reason to expand the Keystone pipeline. Today, we look at how that success sparked an unprecedented amount of well-organized environmental opposition.)

In a way, Alberta Premier Ralph Klein was blindsided.

There was no doubt that Klein’s salesmanship was pivotal to igniting the imagination of the global investment community. What he didn’t expect was how it would capture the attention of environmental non-governmental organizations (eNGOs) around the world.f

These environmental advocates saw the oil sands as “Canada’s single largest contribution to global warming.” Seeing the mine truck parked so close to the White House during the 2006 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in D.C. set off alarm bells. For these advocates, it was a clear indication that both the U.S. and Canada were doubling down on what they viewed as among the dirtiest types of oil.

Oil sands are megaprojects in a democracy. Their footprint and financials can be viewed by anyone with access to the Internet. Their enormous size, and the geographic proximity of one project to the next, makes them uniquely un-photogenic. And when it comes to public trust, oil companies rank low survey after survey.

Initially – and understandably – environmentalists focused their protest campaigns on well-know oil companies and their iconic megaprojects. They did this by drawing attention to the scale of development in the oil sands and its potential impact on local First Nations communities and global climate change. The aim here was to raise legitimate concerns about the pace and scale of development and how it affected host communities, with the objective of closing gaps in regulation that were demonstrably subsidizing oil sands development. They also wanted to call out the increasingly blatant inconsistency between Canada’s international carbon reduction commitments and the rapid growth in emissions from this one sector.

Tactics included tallying up carbon emissions, benchmarking the dirtiness of crudes from around the globe against those from Northern Alberta, and forecasting the total expected footprint of oil sands on globally significant watersheds and migratory birds. Environmental groups began drawing attention to the ever-growing risks posed by seepage from or the complete failure of tailings ponds, which are held in place by some of the largest earthworks dams in the world.

These groups intervened in regulatory review processes on a project-by-project basis. As part of these interventions, they would try to widen the set of environmental aspects under consideration and force assessment of the cumulative effects of development. They would also work to ratchet up environmental performance obligations in the operating permits sought by companies. This led to costly delays for project proponents.

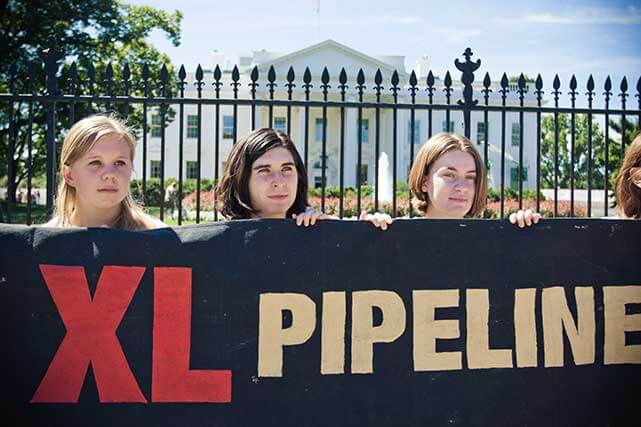

Other groups targeted national and global public opinion. They engaged in street-level protests, including media-friendly direct actions like street theatre and costumed sit-ins. Some conducted commando-like raids into the oil sands projects themselves, where activists scaled oilsands infrastructure to unfurl massive banners for aerial photographers.

These efforts kept the environmental risks posed by oil sands projects in the public spotlight, but offered only modest returns. Public reviews, for example, did not result in a single project being denied permission to proceed. Groups continued to engage diligently with the scientific community, forecasting that cumulative environmental impacts would surpass regional statutory limits and accelerate the decline of ‘at-risk’ species. But these findings were insufficient to drive rejection of individual projects. Yes, intervenors could delay projects, dent economics, and ratchet up regulations over time, but they were unable to curb the appetite for new oil sands projects as crude prices continued to climb.

The coming tide of bitumen meant that a vast network of oil sands export pipelines, including Keystone XL, and a significant retooling of the U.S. refinery fleet would be needed. This set off alarms. The price tag for this enabling infrastructure was estimated to be a staggering $379 billion (U.S.). Environmental groups and their advisors became increasingly concerned that, once built, this huge capital outlay would lock North America into a high-carbon trajectory for generations to come.

This is when activists began to innovate: Rather than target the heart, go after the veins and arteries that keep it pumping.

Increasingly, environmental groups began to target the various paths the oil sands relied on to access markets and capital. An example was opposition to BP’s planned retooling of the Whiting Refinery in Illinois. Due in part to sustained campaign pressure, the project was caught up in three years of regulatory reviews and incurred a reported $1 billion (U.S.) in additional costs. Advocacy groups also supported a set of legislative measures in the U.S. and EU aimed at establishing lifecycle-based fuel standards. The standards would penalize crude imports with a disproportionate upstream carbon footprint, making lower-emission alternatives more favoured in the marketplace.

On the financial side, environmental groups began to publicly link banks and other investors directly to the oil sands and their associated environmental and social impacts. The goal was to increase the cost of capital for oil sands and related pipeline projects, by elevating the reputational risks to the banks, and by forcing these financial supporters to scrutinize risks with more vigour. In one famous example, activists unfurled a two-storey banner in front of RBC Financial Group’s head office and urged the wife of RBC’s chief executive to talk to her husband about the bank’s oil sands investments.

In 2010, the U.S. Senate killed the national carbon cap-and-trade bill, which had been the focus of the U.S. environmental community. With cap-and-trade all but dead in the U.S., environmentalists started looking for a winnable fight. Emerging analysis suggested that it would be necessary to keep 80 per cent of the known reserves of oil, gas and coal in the ground to stop dangerous climate change. It was this “terrifying new math,” as described by journalist and activist Bill McKibbin in the pages of Rolling Stone magazine, that motivated him to convene what has since become the largest series of popular environmental protests to date, starting with a mass rally and arrest in DC targeting the State Department’s Keystone XL review in 2011.

Pinpointing pipelines

When it comes to pipelines, there are many distinct entry points for determined monkey wrenchers. Because pipelines impact many landowners, each with potentially diverging concerns regarding safety, environment and commercial arrangements, a pipeline like Keystone XL offers multiple avenues for opposition.

The specific battle over the Keystone XL pipeline would be fought in at least four distinct domains:

A first battleground was over risks to the safety and local environment of those landowners and communities that would have a pipeline put in their backyard. By 2011, a plague of well-publicized pipeline spills and leaks had undermined U.S. public trust in pipelines, and in particular in Canadian pipeline companies trafficking in oil sands. TransCanada’s peer, Enbridge, was the owner of the pipeline which in 2010 released bitumen into the Kalamazoo River, becoming infamous for the most expensive onshore spill in U.S. history and what an independent review labelled a “Keystone Kops” response. While it is perfectly true that pipeline safety and integrity is a high priority for oil transporters, and that 99.9995 per cent of liquid hydrocarbons transported by pipeline have been delivered safely over the last decade, no landowner or community on the route wants to be one of the .0005 per cent.

As a consequence, TransCanada found itself stymied by an unlikely alliance of conservative libertarians, local and national environmental activists in Nebraska. Together, they gummed up TransCanada’s efforts to secure a right of way through Nebraska’s Sand Hills region and over the sensitive Ogallala aquifer.

A second battleground was over the extent and allocation of economic benefits from the pipeline. Most oil projects, pipelines included, take massive manpower to build and little labour to actually to run. Keystone XL is forecast to create 1,950 construction jobs. Once complete, only 35 permanent American jobs will exist, according to TransCanada. Jobs not only factor into the economic wellbeing of a country, but they figure strongly in a time when economic disparities are the subject of elections.

As for the wider economic dividends, the oil transported to the Gulf Coast would be refined there. Much would be consumed in the U.S., which could lower the U.S. consumer prices at the pumps – somewhat. Outside of property tax paid by TransCanada, the economic activity, taxes and jobs associated with the operation of the pipeline would be localized to refineries on the Gulf Coast. But the lion’s share of the benefits would arguably go to the oil sands producers back in Alberta.

As President Obama would say in late 2014: “I think there has been this tendency to really hype this thing as some magic formula to what ails the U.S. economy and it is hard to see on paper where they are getting that information from. It’s very good for Canadian oil companies, and it’s good for the Canadian oil industry but … it’s not even going to be a nominal benefit to U.S. consumers.”

A third battleground is politics. For Republicans, Keystone is a ‘wedge’ issue that pits organized labour against environmentalists, thus weakening the Democrats. The Republican position is that the pipeline as an engine of economic growth (tweeting about the #KeystoneXLJobs bill, for example) and, by opposing it, the Obama Administration is opposing job creation at a time of high unemployment. On the other side, Democrats use the threat of approval of the pipeline by Republicans to mobilize pro-climate voters.

The final battleground is environmental. Keystone’s direct environmental impacts, assuming no spills or leaks, are pretty similar to that of the thousands of kilometres of other large pipelines running throughout North America. So when advocates against Keystone talk about the environment they are actually drawing attention to the full lifecycle of a barrel of oil, from the decline of Caribou in Alberta’s boreal forests to the greenhouse gases associated with driving a car.

This position has been criticized loudly and repeatedly. Win or lose, Keystone XL proponents argue, the pipeline won’t in itself materially change global carbon emissions. On this front they paint protesters as being misguided. Yet this criticism may betray a misunderstanding of the catalyzing power of the oil sands and its relationship to this pipeline. As a senior journalist from Time magazine put it, questioning activists in their choice of Keystone XL as a target is like telling Rosa Parks that it was wrong to go after the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system in the larger fight against racial segregation .

It’s a position Bill McKibben also holds. “This pipeline,” McKibben has said, “won’t by itself kill the climate.” Rather, the goal is to send a clear message that it’s time to stop exploitation of unconventional fossil fuels. “This is the clearest place to make the fight,” he said.

(Click here for part three. In the final story of this three-part series, we ask whether reports of Keystone XL’s death have been greatly exaggerated, and consider the potential of Alberta’s oil sands to become a laboratory for transformational change, in Canada and around the globe.)