Two and a half years of pandemic living has left the planet with a major plastic hangover. Much of the eight million tonnes of COVID-related trash churned out globally in the first two years of the pandemic was medical waste, but in the sweatpants-clad blur of back-to-back lockdowns, there was also a sharp rise in the single-use plastics involved in getting burrito bowls, groceries and all-things-Amazon delivered to our front doors.

Even before the pandemic, 805 million takeout containers were dished out in Canada in 2019, as were 5.8 billion straws and 15.5 billion plastic grocery bags. Now Canada’s federal government is giving businesses until the end of 2023 to stop selling six hard-to-recycle single-use plastic items, including polystyrene and black plastic takeout containers, cutlery, grocery bags and straws. It’s an important first step that should eliminate more than 1.3 million tonnes of plastic waste, but environmental advocates point out a troubling fact: the ban is aimed at just roughly 5% of Canada’s swelling plastic stream. What about the rest of it?

As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) noted in its latest global plastic report, released in June, “Plastic waste is projected to almost triple by 2060, with half of all plastic waste still being landfilled and less than a fifth recycled.”

“Less than a fifth” may be a generous estimate. In late April, California Attorney General Rob Bonta announced a first-of-its-kind investigation into the recycling claims made by Big Oil. “For more than half a century,” Bonta said in a statement, “the plastics industry has engaged in an aggressive campaign to deceive the public, perpetuating a myth that recycling can solve the plastics crisis.”

The reality, he added, is that the vast majority of plastic cannot be recycled. The bombshell investigation was announced on the heels of a damning report released by the U.S. Department of Energy a few days earlier, which concluded that only 5% of plastic has actually been getting a second life through recycling. That’s particularly bad news considering the United States generates more plastic waste than any other country. But the whole world is having a tough time figuring out what to do with its plastic.

For more than half a century, the plastics industry has engaged in an aggressive campaign to deceive the public, perpetuating a myth that recycling can solve the plastics crisis.

–California Attorney General Rob Bonta

Fortunately, there’s also been a surge in grassroots reuse-and-refill businesses around the globe. While the refillable mugs and reusable bags of the zero-waste movement were vilified in the early days of the pandemic, they’re back on the upswing. Independent start-ups like Suppli in Toronto and DeliverZero in New York have been tackling the takeout waste crisis by offering reusable container services to local restaurants.

Now some major fast-food chains are promising to get in on the action.

In a partnership with TerraCycle’s circular packaging service, Loop, refillable takeout containers may be coming to a Burger King near you. At least if you live in the United Kingdom or New Jersey, where BK outlets will be trialling deposit return systems for refillable burger “clamshell” packaging, soda cups and more. In Canada, BK’s parent company, Restaurant Brands International (RBI), partnered with Loop and Tupperware Brands to pilot reusable food packaging containers for the Tim Hortons chain late last year.

RBI isn’t the only corporation scrambling to meet public commitments to shift to fully recyclable, reusable or compostable packaging by 2025. Similar pledges have been made by more than 1,000 organizations. In May, Body Shop announced that it’s reviving plans to roll out refill stations across the U.S., and Dove is now offering deodorant in slick refillable containers. Earlier this year, Coca-Cola promised to make a quarter of its beverage containers “refillable/returnable glass or plastic bottles” by 2030.

Whether corporate efforts to introduce refillable containers go beyond novelty or pilot projects remains to be seen. On World Refill Day, June 16, more than 400 organizations released an open letter to the CEOs of five of the biggest consumer goods companies (Coca-Cola, Nestlé, PepsiCo, Unilever and Procter and Gamble), urging them to support “transparent, ambitious and accountable reuse and refill systems.”

In Canada, dozens of environmental groups and zero-waste businesses are calling for increased government support for reuse-and-refill initiatives. Sarah King, Greenpeace Canada’s head of oceans and plastics campaign, says that the federal government has been “stalling on fully embracing refill and reuse funding.”

King says, “Canada will only meet its zero plastic waste by 2030 goal if it acts now to cut production of all non-essential plastics and creates a strategy to scale reuse and refill infrastructure nation-wide to accelerate a transition to truly zero waste, low carbon systems.”

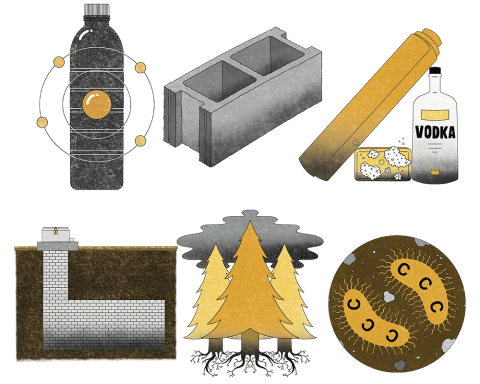

The OECD agrees that bans on a “tiny share” of plastic waste will get us only so far. Its earlier February report on plastic concluded that “bans and taxes on single-use plastics exist in more than 120 countries but are not doing enough to reduce overall pollution.” The OECD is calling for “greater use of instruments such as Extended Producer Responsibility schemes for packaging and durables, landfill taxes, deposit-refund and Pay-as-You-Throw systems.”

Bans and taxes on single-use plastics exist in more than 120 countries but are not doing enough to reduce overall pollution.

–OECD

While announcing Canada’s new plastic ban June 20, Environment and Climate Change Canada didn’t mention any of the above, but the ministry did note that “moving toward a more circular economy for plastics could reduce carbon emissions by 1.8 megatonnes annually, generate billions of dollars in revenue, and create approximately 42,000 jobs by 2030.”

In a sea of despair over rising plastic pollution, some hopeful signs are floating to the top. As of July 1, India is banning a long list of single-use plastics, including plastic wrap, cutlery and plastic sticks. Austria is mandating that 25% of beverage bottles be refillable by 2025, while Chile is mandating a 30% quota.

Back in California, ExxonMobil put out a statement denying the attorney general’s charges that it’s been misleading the public on the recyclability of plastics: “We are focused on solutions and meritless allegations like these distract from the important collaborative work that is underway to enhance waste management and improve circularity.”

Of course, Exxon has also denied that it’s known about climate change for 40 years while spending millions on funding climate-change-denying think tanks.

Judith Enck, president of the environmental group Beyond Plastics and a former Environmental Protection Agency regional administrator, told Inside Climate News that California’s investigation is “very significant.”

“[It has] the potential to finally hold plastic producers accountable for the immense environmental damage caused by plastics.”

A version of this article appears in the summer issue of Corporate Knights magazine.