According to some mainstream media reports, America will soon be “awash in oil.” Natural gas, meanwhile, seems to be pouring out of cracks in the ground across North America. Energy crisis? What energy crisis?

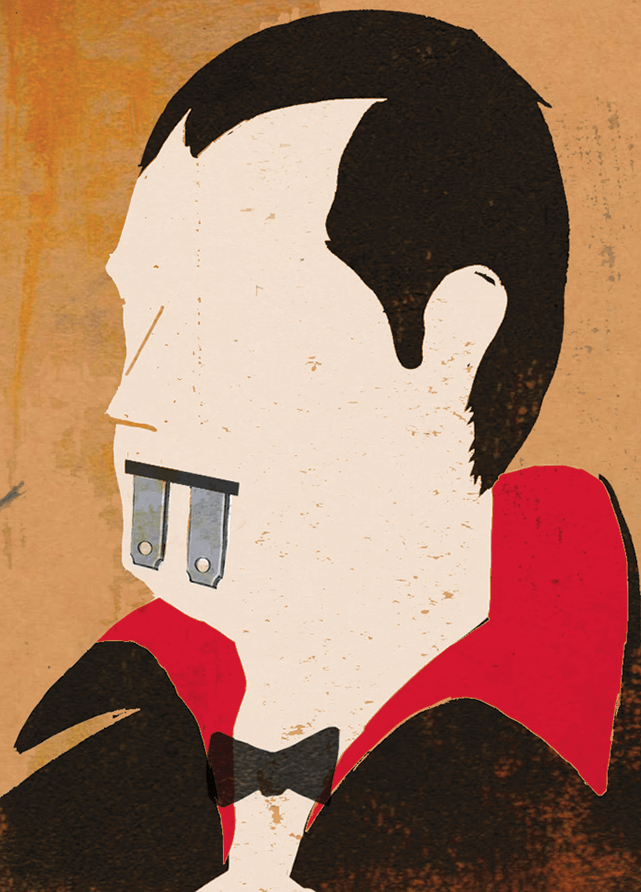

In his new book Green Illusions, Ozzie Zehner, visiting scholar at the University of California, Berkeley, writes that there never really was an energy crisis. What we have, he argues, is a consumption crisis that is being compounded by all the gizmo-green technologies we are throwing at it. Zehner subtitles his book “The dirty secrets of clean energy and the future of environmentalism,” and he devotes the first half of his work to a “colonoscopy” of clean-energy technologies.

Zehner questions the cleanliness of solar-panel manufacturing and the long-term effectiveness of the panels, and claims that even if they were free, the costs of installing, connecting, maintaining, cleaning, insuring and eventually disposing of photovoltaics make them uncompetitive.

Many have disputed his position. But you cannot dispute his questioning the logic of slapping solar panels on the roofs of suburban homes to “supplement the power for the wine chillers, air conditioners and clothes dryers of the nation” instead of designing and insulating those houses properly in the first place.

Similarly, Zehner has been criticized for his claim that electric and hybrid cars are really running on coal, nuclear power and lithium mines and that overall, they have no real environmental benefits. However, one cannot dispute his comments that the electric or hybrid car does little to deal with the larger ecological impacts of sprawl, and that “a car’s odometer may be more environmentally telling than its fuel gauge.”

Zehner attacks every alternative energy source with glee, from easier targets like hydrogen and biofuels to weightier sources like nuclear and wind; sometimes with too much glee and perhaps too little research. I was surprised that he doesn’t appear to know the difference between a ground-source heat pump, inaccurately called geothermal by American salespeople, and real geothermal from lava and hot springs.

This is all a great shame because it distracts readers from the real value of the book, in which Zehner asks the question: “Why do the options of wind, solar, and biofuels flow from our minds so freely as solutions to our various energy dilemmas, while conservation and walkable neighborhoods do not? Why do we seem to have a predisposition for preferring production over energy reduction?”

Zehner’s provocative suggestions will make any Republican candidate choke. He starts with women’s rights and population control. Given the average carbon footprint of an American born today, he calculates that “just lowering American teen births alone to European levels would prevent the need to generate over 30 billion kilowatt-hours of energy annually, the equivalent of $500 billion in solar panels per year.”

His other suggestions are only slightly less radical. Zehner urges us to reduce conspicuous consumption, arguing that we suffer as a society from “affluenza” – a disease inculcated from an early age through advertising. He suggests the banning of all marketing to children as a first step in the right direction.

Energy efficiency should also be a top priority. “America has plenty of energy, more than twice as much as it needs,” he writes. “We just waste most of it.” The key, in his view, is to improve our buildings’ insulation, design and technology so that they consume energy much more efficiently.

He also puts much weight on transportation and planning. “The fact that communities hold bake sales to finance bike racks and safe thruways for students while the fetishized solar-cell industry bathes itself in billions in public funds is an inglorious national embarrassment,” he opines, suggesting that walkable, bikeable, denser communities be given priority over car culture.

Finally, and perhaps most controversially, he calls for creation of an energy tax on all forms of energy, rather than just carbon-based energy sources, to encourage the embrace of energy efficiency and stifle the rebound effects that sometimes result.

Do that, he writes, and “Future environmentalists will drop solar, wind, biofuels, nuclear, hydrogen and hybrids and focus instead on women’s rights, consumer culture, walkable neighborhoods, military spending, zoning, health care, wealth disparities, citizens’ governance, economic reform and democratic institutions.”

A quick Google search shows that Green Illusions has been cherry-picked by climate skeptics and right-wing websites who would choke on the meat of it if they actually read the whole book. Bashing investment in solar and electric cars is popular in certain political circles right now; Zehner has given them plenty of ammunition, mostly duds.

It would have been a less popular but much better and more accurate book if he had stuck to his positive proposals for change, found in the second half of the book, instead of spending the first half feeding the fury of anti-clean energy trolls on the Internet.