On November 27, Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney signed a memorandum of understanding with Alberta Premier Danielle Smith to try to get a pipeline built from the oil sands to the coast of British Columbia. The “grand bargain,” as Smith dubbed it, introduces two sets of promises: Ottawa commits to opening every door it can to pump heavy diluted bitumen to tidewater, so long as a private backer and Indigenous partners get on board; and oil companies will spend billions to reduce upstream greenhouse gas emissions and earn their barrels the moniker “low carbon” – something climate experts say is little more than a pipe dream.

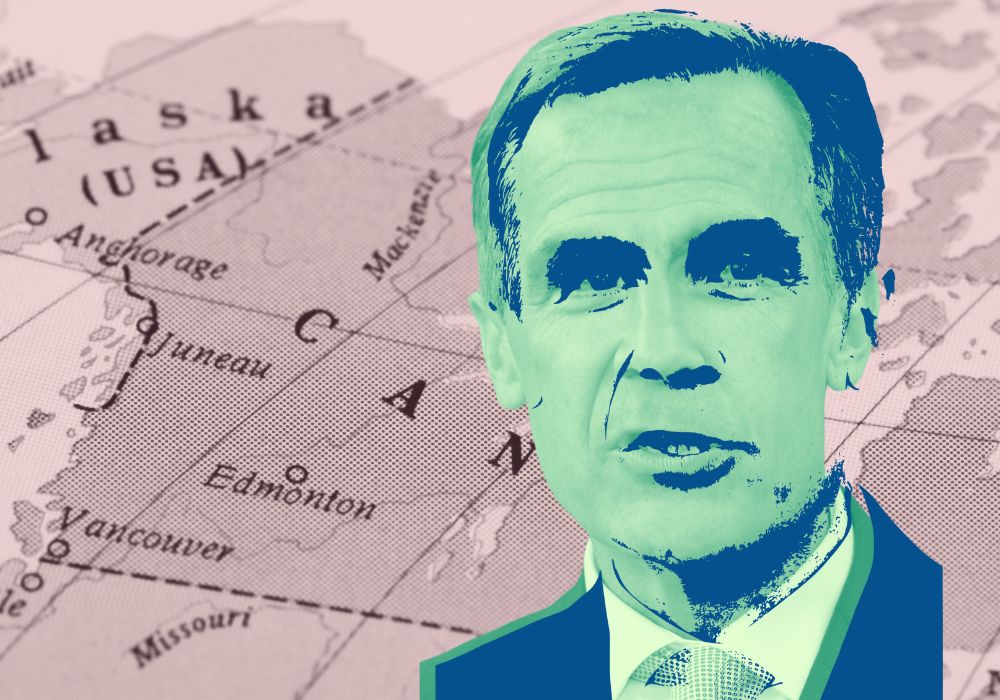

One year earlier almost to the day, then-UN Special Envoy on Climate Action Mark Carney gave the keynote address at the Sustainable Finance Forum in Ottawa, in a speech titled “Transformational Leadership.” At the time, Carney’s reputation as a climate leader was gold-plated. Regarded as one of the architects of modern sustainable finance, his Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net-Zero had corralled hundreds of major banks, insurers and asset managers to pledge funds for the energy transition. To add to his veneer, he was already being chased by reporters about his prospects for Canada’s top office.

A lot has happened in a year. Carney and his central bank bona fides soon became the hottest commodity on the Canadian political map, for an electorate that was suddenly feeling under siege by a Donald Trump White House. He won the Liberal leadership, then eked out a come-from-behind win in the federal election, upending what had looked to be the dawn of a new Conservative era in Canada.

Now, these two moments – the finance summit and the pipeline deal – mark a full turning for Carney, from climate hero to, in the eyes of some, climate villain. Even so, Carney stated his convictions clearly back at the Ottawa event in 2024. Asked if the federal government should invest in decarbonization in high-emitting industries, Carney said, “I’m suggesting we should run towards that, because that, in the end, is going to have the highest impact on the climate.”

As promised, Carney has now stamped his approval, and his reputation, on so-called decarbonized oil and the infrastructure to move it. It’s a high-stakes gamble, at a different inflection point in the climate battle than the showdowns over the Keystone XL and Trans Mountain pipeline projects. The politics are shifting, as evidenced by the shuttering of Carney’s net-zero banking alliance in October.

The myth of low-carbon oil

So-called decarbonized oil hinges on the deployment of expensive technology to snatch carbon from smokestacks and pump it underground, known as carbon capture and storage, or CCS. While there are many CCS projects already operating around the world, albeit mostly for methane gas processing rather than oil, the technology has not been proven at scale as a reliable climate solution. Critics point out that it is costly, inefficient and unlikely to ever exist independently of government subsidies.

Whether CCS turns out to make sense economically, the marketing belies the fact that oil cannot be decarbonized. It is made of carbon, and you still need to burn it to use it, which is when most of the pollution is released. The word “decarbonization” exists to set the widest possible frame around what reducing carbon dioxide emissions can mean. In this case, it means roughly 10% to 20% of the full life-cycle emissions of a barrel, and those reductions come at such a high price that any market for it is conjectural at best.

The Pathways Plus system agreed to in the new MOU, billed as “the world’s largest carbon capture, utilization, and storage project,” will cost approximately $16.5 billion to deploy in the oil sands, and that’s just for the underlying infrastructure to move the CO2 around and store it. The participating companies still need to buy their own carbon-capture units and install them at their extraction and upgrading plants.

RELATED STORIES

Few in the world of net-zero finance are buying it. Carney is “legitimizing doublespeak,” says Kyra Bell-Pasht, director of research and policy at Investors for Paris Compliance. “By using greenwashing terms like ‘decarbonized oil’ on his pulpit, he is setting a standard of misinformation at the highest level,” she writes in an email.

Carney has already paid a high political cost for backing the oil and gas industry’s plan to increase production in the era of climate consequences. Just hours after the deal was signed, former environment minister Steven Guilbeault quit his new cabinet post as minister of Canadian culture, saying that he could not have looked himself in the mirror if he’d gone along with the prime minister. Two core members of the Net-Zero Advisory Body, which gives guidance to the government on reducing emissions, also stepped down over the pipeline deal: Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, and Simon Donner, the group’s co-chair. The Assembly of First Nations chiefs passed a unanimous emergency resolution echoing coastal leaders who say the project “will never happen,” while B.C. Premier David Eby was more tepid but still dismissed the deal as a “distraction.”

Premier Smith, too, paid a price for collaborating with Ottawa, which Alberta premiers can little afford to be seen doing. She was loudly booed at her party’s annual general meeting just a few days after signing the MOU.

More than half of Canadians still support the proposed pipeline, but any push by Carney would surely be a long, bruising effort, and the prize at the end looks very much in doubt. At the Sustainable Finance Forum in 2024, he told the crowd, “We may be the first generation that understands the risks associated with climate change. We’ll also be the last generation that can do anything about it.” Building an oil pipeline is not something most people in that room would have picked for a next step.

Mark Mann is the managing editor at Corporate Knights. He is based in Montreal.

The Weekly Roundup

Get all our stories in one place, every Wednesday at noon EST.