IRON MOUNTAIN, Michigan – Wherever Jim Peters goes, a contingent from the Committee to Ban Fracking in Michigan follows. The operations manager at NorthStar Energy LLC and representative for the Michigan Oil and Gas Producers Education Foundation admires their perseverance, but says they’re not there to have a discussion. “They just poison the atmosphere for everyone else,” he complains to a group of journalists gathered on the shores of Lake Antoine. The fracking wars have touched down in “the Wolverine State.”

Hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is a process wherein rock is fractured by a pressurized liquid. Popularized by the discovery of horizontal drilling in the late 1990s, it has led to the natural gas and tight oil boom currently powering the ongoing energy revolution in North America. Thirty-one states now contain potentially viable shale gas plays, including Michigan.

Few issues cause as much political heartburn as the expansion of fracking in the United States. The International Energy Agency estimates that U.S. gas output will continue to increase for the next five years, on top of the sixfold increase that has occurred since 2007. Proponents such as John Griffin, a spokesman for the American Petroleum Institute in Michigan, believe that the continued expansion of natural gas is a necessity. “It’s strengthening America’s energy security, and creating jobs at home,” says Griffin, “all while reducing overall emissions.”

Opponents of fracking are convinced that industry is glossing over the environmental consequences. From fears about fresh water depletion, methane emissions and earthquakes, community opposition to new wells has been fierce. But the greatest concern remains groundwater contamination. To dislodge oil and gas from within rock formations, a mixture of sand and chemicals is added to water during the fracking process. Local residents are apprehensive about these chemicals infiltrating local water supplies. Further complications arise during the treatment process, as wastewater needs to be stored before being treated or reused.

There has been some evidence of groundwater being affected around drill sites, including a recently published study by researchers at the University of Texas that found higher levels of heavy metals, including arsenic, in groundwater around fracking sites in the Barnett Shale deposit. Another study released this year found elevated radium levels in wastewater discharged from a Pennsylvania treatment plant. Other research, however, has found no such link. An ongoing U.S. Department of Energy study in Pennsylvania tagged tracers with unique markers. Described as the first independent look at the movement of toxic chemicals during drilling operations, a year in it has showed no evidence of chemical contamination of drinking water.

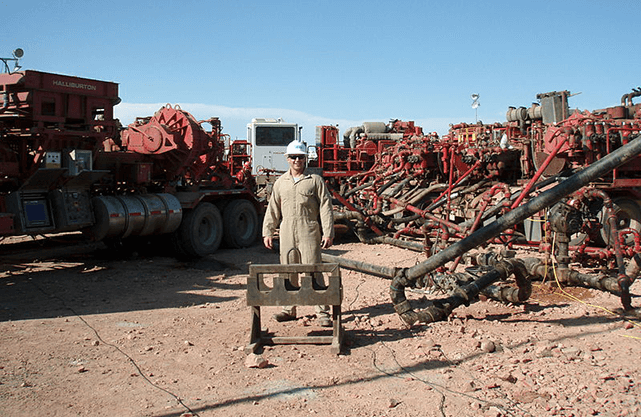

Little federal regulation currently exists on fracking, largely due to the original passage of the Energy Policy Act of 2005. Language within the bill, known as the “Halliburton loophole,” exempted drilling companies from complying with the Clean Water Act. Subsequent bills in Congress aimed at defining hydraulic fracturing as a federally regulated activity under the Safe Drinking Water Act have gone nowhere, which has forced individual states to establish their own guidelines.

Wyoming was the first state to require disclosure of fracking fluids to the public in September 2010, followed by Arkansas, Pennsylvania and Michigan. Fifteen states now have laws on the books, with legislation pending in an additional seven states. Some regulatory structures only require confidential disclosure of fluids to regulators, none of which are released to the public. Even in states that require public disclosure, according to Jennifer McKay, a policy specialist for the Michigan-based Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council, a “trade secret” exemption allows companies to omit information to protect intellectual property.

At a recent State Senate hearing in Texas, Marc Edwards, Halliburton’s senior vice-president of completion and production, defended the necessity of trade secrets. “Halliburton has the only frack fluid that is sourced entirely from the food industry,” he told committee members. “Without proprietary protection, it would not have invested in its development.” Lawsuits are underway in several states challenging the use of trade secret exemptions, including one suit currently pending before the Wyoming Supreme Court.

Twelve states have made the submission of chemicals to the website clearinghouse FracFocus a disclosure requirement. The online registry for chemicals, with 45,000 records from more than 400 companies, is managed jointly by the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission. Amy Mall, a senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council, testified at the same hearing as Halliburton about the problems with the system. “The problem with FracFocus is that it’s not a government website with specific requirements and a legitimate process to determine what actually is a trade secret,” she explained. A Harvard Law School study in April showed some companies claiming a chemical as proprietary in one state while disclosing it in another.

Some companies, like Canadian natural gas giant Encana, have developed their own internal rules for screening chemicals with the potential to impact human health. The Calgary, Alberta-based company, which has extensive shale gas plays across the U.S., launched the Responsible Products Program in conjunction with a third-party toxicologist. “To give you a scope of the program,” says Spencer Forgo, a communications advisor for the company, “over the course of 2012 we assessed in excess of 350 fluid system products across our operations.” Fluids containing arsenic, cadmium, chromium and other metals have been banned by Encana already, and the company is pushing to adopt the practice across the industry in North America.

Fracking remains in its infancy in Michigan, with only 19 new wells having been drilled since 2010. That pales in comparison to the 13,540 wells drilled in Texas alone in 2012. It’s for this reason that proactive regulations should be put in place to ensure the growth of a well-regulated industry, says McKay. “Our top priorities remain the full disclosure of chemicals, paired with baseline testing,” she said. Companies are not required to release information on fracking cocktails until 60 days after fracking occurs, making testing for specific fracking fluids all the more difficult. Some companies, such as Encana, offer free tests to homeowners who live near wells, but homeowners are often wary to accept these offers. “Some residents just don’t trust companies to remain objective,” says Emily Whittaker, a policy specialist at Freshwater Future. In August, the environmental NGO began offering its own testing program for any Michigan citizen with concerns.

With many fracking cocktails proprietary and likely to remain so in the future, those conducting tests often don’t know what they’re looking for. Scientists have been looking for alternative ways around this, including the idea of putting tracers in the fracking fluid. Using a similar method as the Department of Energy study, competing companies that began at Rice University and Duke University are racing to bring trace fracking fluids to market. A field test is currently underway at a well site in Texas. The appeal of this technology is that it would allow companies to continue to guard trade secrets, while adding definitive traceability into the process.

Lawmakers have already put forth bills in the Texas legislature to mandate the use of tracers, but industry remains non-committal on the subject. “If companies want to adopt this on a voluntary basis they should go right ahead, but in my opinion adding another layer of regulation for companies is not necessary,” says Barclay Nicholson, an energy and commercial litigation attorney at Norton Rose Fulbright’s Houston office.

For some, hydraulic fracturing will never be safe enough to accept. Activists are currently circulating a petition to place a Michigan fracking ban on the 2014 state-wide ballot. LuAnne Kozma, the spokesperson for Ban Michigan Fracking, explained her reasoning when announcing the creation of the group. “We know enough now to demand a ban,” she declared in a press release.

This article was made possible with the generous support of the Institutes for Journalism and Natural Resources.