True story: upon returning home from a grocery store in Nelson, British Columbia, a customer noticed a considerable discrepancy on his bill. He immediately called to alert the store that he was charged only $12.69 for the jumbo 3.75-kilogram tub of yogurt priced at $23.99.

There was an unmistakable pause on the other end of the phone.

As the customer noted, a pricing error like this gone unchecked may have racked up thousands in lost revenues for the grocer.

At a time when trust and respect for grocers might be at an all-time low, this was a window into an alternate reality. This customer genuinely cared about the business because he’s one of 16,000 customers who own it.

Known as “food co-ops,” these consumer-owned grocery stores number in the hundreds across the United States and Canada, with many commanding generous market share in the communities in which they operate. Nelson’s Kootenay Co-op,* where this story unfolds, competes successfully with supermarkets owned by Western Canada’s “Big Three”: Jim Pattison Group, Sobeys and Loblaw. With revenues of $26 million, Kootenay Co-op is the third largest private employer in the city of 11,000. The head office? Inside the store. The CEO? Sitting around the corner from the teenaged dishwasher. The board of directors? One-hundred percent local.

Most food co-ops share similar origin stories. At some point, people became fed up with the grocery stores they relied on, and, rather than continue finger-pointing, they chose a more empowered position and built their own. Co-ops often arise as the “new growth” that follows the metaphoric wildfires of war, greed, oppression, economic inequality or collapse, and they’re a product of social revolution – a vision for a new way of living. Whatever the cause, co-ops often materialize when people are ready for change.

We seem to be at another one of those junctures. With tempers flared over food prices and trust eroded by price-fixing scandals, it is safe to say consumers are fed up with Big Grocery. But are they fed up enough?

This might be the most opportune time in the last 50 years to question our deepest assumptions about how we buy our food.

Privatization, prices and profits

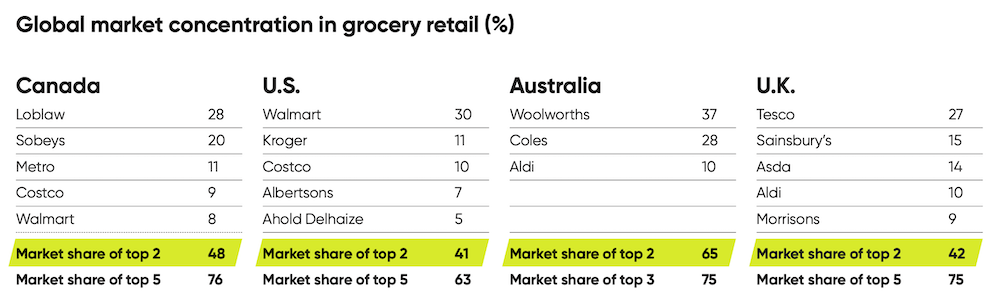

Imagine a world where nearly 80% of the sale of and access to drinking water is handled by five corporations. That is Canada’s grocery landscape – how we access food. And with the pending merger of two of the U.S.’s largest grocers – Kroger and Albertsons – concentration in that country’s grocery sector may become quite similar.

With less competition comes higher prices. Look no further than Canada’s mobile phone market – where infamously high cellphone bills have become a red flag to consumers worldwide regarding the risks of market concentration. Canadians were hopeful when Wind Mobile entered the market in 2008, but the “Big Three” telecom companies fought hard to keep it out. Canada’s telecommunications regulator found that Wind was charged “many times more” to roam on the Rogers network than the price the telecom giant offered its customers or other mobile carriers. Wind struggled until it was eventually acquired by another telecom giant, Shaw, in 2016.

Should we expect any different from Big Grocery?

For decades, grocery giants have placed entire neighbourhoods at the mercy of property controls – used to keep other grocery stores from being constructed nearby. When a vacant 2.26-acre site in Dundas, Ontario, was put on the market in 2021, residents learned of a restrictive covenant registered on the land by grocery giant Metro Inc. The restriction prevents any grocer from competing with Metro’s nearby store, a 12-minute walk away, and it protects Metro’s monopoly position as the only full-service grocery store in Dundas. Similar restrictions appear on deeds across Canada and the U.S. Grocery giants are in the business of selling food – and restricting access to it.

But behaviours like these can easily take a back seat to prices. Price has always been the dominant lens through which consumers engage with grocers. Not surprisingly, recent grocery grievances have zeroed in on profits – and for good reason: two-thirds of shoppers are feeling pinched by rising grocery bills, and media reports have focused considerable attention on surging profits and alleged greed among the giants.

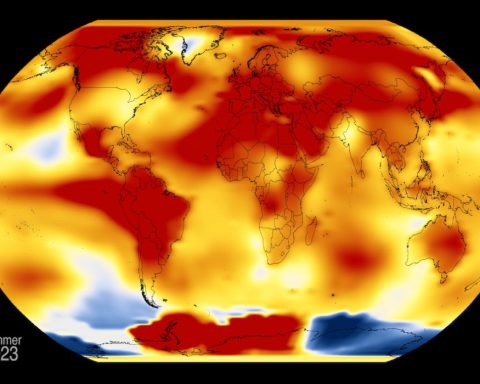

Yet, grocer profits offer a murky field of view into the complexity of food prices, particularly the challenge of parsing out the origin of profit margins at these more-than-just-food mammoths. Add in geopolitical instability, supply chain disruptions, record-smashing droughts and floods, labour shortages and currency fluctuations, and it becomes clear that even if greed is in the mix, it is but a thin slice of influence on recent price increases.

More meaningful would be to use the dramatic rise in food prices for a wider inquiry into the privatization of food access, grocer accountability and how lack of competition affects prices and innovation throughout the food supply chain.

To what degree have recent breakdowns of supply chains been a burst bubble on the promise of a low-cost globally dependent food system? Has 100 years of demanding low-priced food pushed the food system to hit the food-price floor? Is “lower” sensible, given the externalized costs of cheap food on consumer health, worker welfare and the environment? And if not, might our focus turn to boosting the capacity of people to pay for food – living wages, housing affordability – and protecting any gains from being extracted in the marketplace? By increasing consumers’ capacity to pay for food, we put a stop to the possibility that the race to the bottom on price has perverted our sense of what food is actually worth. We also protect the possibility of a viable alternative: the independent grocers, the small- to mid-scale food producers, who would no longer be at the mercy of consumers’ distorted food-price expectations.

The shadow of restraint

The common assumption is that the best way out of overly concentrated markets is through intervention.

In May, Australia’s Competition & Consumer Commission blocked Woolworths’ proposed acquisition of a single independent grocer in a Canberra suburb. With Australia’s whopping grocery duopoly commanding 65% of the market, the blocking of this acquisition is notable. It does, however, demand deeper reflection on how industries respond to regulatory restraint.

In the U.S, post-Depression-era restraints – which limited price increases, protected wages and required suppliers to offer independent grocers the same pricing offered to the chains – compelled American grocers to form the National Association of Food Chains and the Super Market Institute. The lobbying and public relations efforts of the two groups helped shape the modern grocery industry; they eventually merged to become what today is FMI – a powerful food-industry trade association influencing public policy and setting industry standards.

Strengthening the regulatory environment has often strengthened the industry being regulated – forming deeper coordination among the dominant players.

In Canada, market dominance in grocery may already be beyond a “tipping point.” A Competition Bureau report released in June suggested attracting new international players to increase choice and ultimately lower food prices. But it’s a rather fanciful proposition to any grocer not already a member of the inner circle. Five years after Canada’s bread price-fixing scandal erupted, no charges have been laid against any grocer, and Loblaw was granted immunity for its cooperation in the Competition Bureau’s investigation. As industry expert Sylvain Charlebois told Global News, “Why would you go into a market where there are suspicions of collusion when you are not part of the family?”

Greed-free grocery

Embedded in politicians’ and consumers’ recent rebuking of Big Grocery is an expectation that grocers should act in the best interests of customers, workers, suppliers, communities and planet. While that’s an ideal behind stakeholder capitalism, where businesses serve the interests of all their stakeholders, not just shareholders, it has yet to materialize among the grocery giants. But a grocery store akin to a non-profit that uses its bottom line to achieve these “best interests” is no dream.

In April, the Sacramento Natural Foods Co-op returned US$200,000 of its profits to more than 9,000 of its customers as store credit. Each customer’s portion was determined by their annual purchases. It was as if the grocer was apologizing for charging its customers too much. But this is business as usual at food co-ops.

The remainder of the grocer’s profits remained within the store, benefiting customers, workers and community – effectively making this grocer a for-profit non-profit. With transparency like this, customers can trust that prices are the best the grocer can sell at. Otherwise, the customer directly receives or benefits from the excess.

Power is evenly distributed in other ways, with the thousands of owners at a food co-op empowered to vote annually for their grocery store’s board of directors. Unlike corporate shareholders, a food co-op shareholder is entitled to only one vote.

Co-ops are price competitive, too. Notwithstanding the efforts of food co-ops to pay their suppliers well, particularly on local and traceable products, Kootenay Co-op’s pricing of national brands is on par with Loblaw – Canada’s grocery Goliath – according to research conducted in 2020. Community Food Co-op in Bellingham, Washington, compared thousands of products with nearby Fred Meyer (Kroger), Whole Foods (Amazon) and Haggen (Albertsons) and found its pricing on par with or lower than all three.

To support its lower-income customers, the Sacramento co-op offers a daily 15% storewide discount.

While Canada’s Competition Bureau failed to mention co-operative grocers as an alternative in its report, food co-ops are serious players on both sides of the border. Combined sales of the 320 food co-ops in the U.S. tops an estimated US$3 billion.

Today, the success of the more seasoned American co-ops is directly supporting what has become the most significant wave of new food co-op development since the 1970s. Many of the stores in development are targeting low-income neighbourhoods with little or no access to grocery stores or healthy food – with some looking to reverse decades of structural racism.

Meanwhile, in Western Canada, the largest food co-ops – operating under the brand “Co-op” and with hundreds of locations – own their own wholesale distribution system that also services a network of Inuit- and Dene-owned co-ops in Canada’s North.

While a co-operative grocer can fail like any other business, no food co-op has ever been sold to private interests. Such a move would require a vote by its thousands of customer-owners who depend on the store. This makes co-operatives a seriously durable model to protect the neighbourhood grocer.

Whatever it is that prompts the development of a co-operative, the common denominator is a shared belief that people, not government or private interests, are most capable of stewarding that which is most important to them.

If a grocery store being held accountable by its customers sounds radical, perhaps it shouldn’t. The climate emergency, corporate concentration in food and rising costs of living are nothing short of dramatic. Maybe the response should be too.

Jon Steinman is the author of Grocery Story: The Promise of Food Co-ops in the Age of Grocery Giants. He lives in Nelson, B.C.