Reparations for climate damage, international climate finance, the energy crisis and the geopolitical snarls caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine are taking their place as central issues as the clock winds down to the launch of this year’s United Nations climate summit, COP 27, in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt.

Senior officials in the Biden administration revealed last week that the world’s biggest historical carbon polluter had “decided to support formal UN negotiations over possible compensation and assistance to countries that suffer devastation from storms, floods, and droughts made far worse by climate change,” Bloomberg writes. That decision closes some of the negotiating gap between at least one major emitter and the call from small island states for a “response fund” for vulnerable nations.

“But while the U.S. is supporting dialogue on the issue,” Bloomberg reports, the country’s negotiators at the COP “are discouraging any explicit push for new aid or funding in an agenda item framing the talks. That would put the U.S. at odds with a large group of vulnerable nations which will be led at the talks by Pakistan, where floods have left more than 1,700 dead and caused some $30 billion in losses.”

While Bloomberg says the devastation in Pakistan “has given the politics of loss and damage a new urgency,” the discussion has been going on for decades, with painfully little progress.

“After decades of insufficient action from big, powerful, and wealthy nations,” the “unfortunate reality of today is that loss and damage have become the paramount issue for climate policy,” said Saleemul Huq, an advisor to the 55-nation Climate Vulnerable Forum. “Loss and damage punishes above all the poor, the vulnerable, and those least responsible for—and least equipped to handle—the severe and mounting catastrophes brought about through the climate crisis.”

“It is more than 30 years since vulnerable nations first demanded support to address the losses and damages caused by fossil-fuelled storms, floods, and sea level rise,” Climate Home News writes. “Rich countries, wary of endless liabilities, pushed back. But with costs of extreme weather mounting, the issue has become unavoidable. It is set to dominate negotiations in Sharm el-Sheikh.”

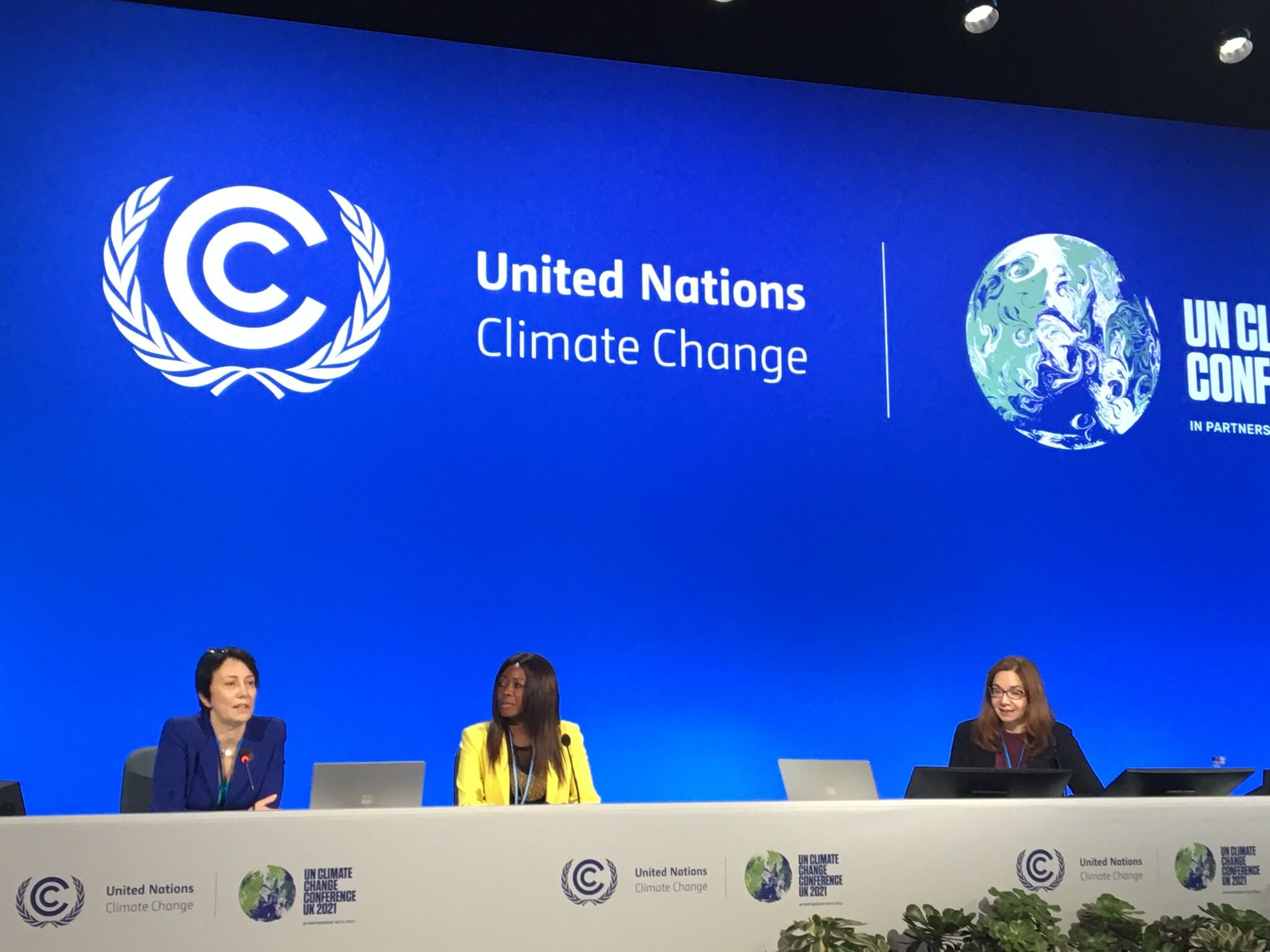

The plan put forward by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) for a Loss and Damage Response Fund “is an evolution of the ‘facility’ proposed by developing countries and opposed by wealthy ones at the COP 26 Glasgow summit last year,” Climate Home says. But “discussions on how to provide financial support to developing countries hammered by worsening climate impacts remain one of the most contested issues in the talks.”

Leading into the conference, the V20 bloc, representing the countries most vulnerable to climate impacts, is demanding a plan to fund the response to extreme weather, The Guardian reports. “The reason we are talking about loss and damage is that we have failed on adaptation finance for years,” said Maldives Environment Minister Shauna Aminath.

Funding shows what matters

Aminath put the world’s richest countries’ slow uptake on the climate emergency in stark contrast to their response to the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine.

“It’s very obvious that it’s not a lack of money, or a lack of technology, that is the problem,” she said. “The issue is the lack of political will and the refusal to see the climate crisis as an emergency.”

With that contrast front and centre at the third COP ever held in an African nation, “many observers believe it is possible that the developing countries will make a dramatic stand at the talks over how their plight has perpetually been placed on the back burner by their more powerful treaty partners,” Inside Climate News writes. “COP 27 could even end in no agreement, they warn, because of the rift between rich and poor nations.”

Aminath added that international financing must go beyond the immediate physical damage from a hurricane, flood, or heat wave to include impacts on health and education, particularly as climate response erodes vulnerable countries’ fiscal base and their ability to fund human services.

“These are the social issues that are left behind after the donors leave [in the aftermath of disaster],” she told The Guardian. “There is also internal displacement, and the resulting problems with social integration, which are very important.”

India will also be emphasizing climate finance during COP 27 negotiations, The Hindustan Times reports, beginning with the US$100 billion in international climate finance that wealthy countries promised in 2009 and have consistently failed to deliver. Last week, Germany increased its annual commitment to €5.3 billion, Clean Energy Wire writes.

A ‘geopolitical hurricane’

Quite apart from the urgent issues on the COP 27 table, delegates in Sharm el-Sheikh will have a “geopolitical hurricane” to navigate, Bloomberg Green reports.

“The last time world leaders got together for a climate summit, the backdrop was thoroughly menacing,” the news agency recalls. “A pandemic had decimated national budgets. Poor countries were up in arms over the hoarding of COVID-19 vaccines by the same wealthy nations whose fossil fuel consumption did most to warm the planet. Relations between the two largest emitters, the U.S. and China, had devolved into zero-sum skirmishes over everything from trade to Taiwan.”

And “those were the good old days,” write reporters Marc Champion and Salma El Wardany.

In the last year, “the geopolitical context that shapes all international diplomacy has gone from tense to precarious,” they explain. “The war in Ukraine has divided nations over what some saw as a fight between Russian and Western interests, and supercharged an energy crisis that risks shredding COP 26’s most concrete achievement: a global consensus to cut down on coal.”

A coal phasedown and an end to economically “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies were two of the main takeaways from last year’s climate negotiations. But now, “COP 27 is to be convened while the international community is facing a financial and debt crisis, an energy prices crisis, a food crisis, and on top of them the climate crises,” said Egyptian Foreign Affairs Minister and COP 27 President Sameh Shoukry.

“In light of the current geopolitical situation, it seems that transition will take longer than anticipated.”

COP 27 will also see the bizarre spectacle of Ukraine and Russia each trying to claim responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions—from a chemical plant in Armyansk, to diesel fuel burned during Russian military operations—in Crimea and other Ukrainian territory that Moscow currently occupies, The Washington Post reports.

“Ukrainian policy-makers say their goal is not to look as good they can on climate rankings,” the Post says. “Instead, they want UN discussions to reflect their legal claims over what the vast majority of the world continues to recognize as Ukrainian land, even if Russia is in possession of the territory.”

“It’s not about the climate arguments—it’s about our territory. Russia is trying to use all venues to legitimize the illegal annexation,” said Ukraine’s former deputy energy minister Alex Riabchyn, a member of the country’s COP negotiating team since 2015. “Every single document that doesn’t have footnotes, that doesn’t say Crimea is Ukrainian, is a hybrid diplomacy strategy of Russia to legitimize this.”

Egypt’s presidency under scrutiny

The Egyptian COP Presidency is also taking heat for key aspects of its communications strategy for the COP, after months of concern about tortuous conference registration rules, exorbitant hotel costs for cash-strapped delegates, and hostility toward civil society participation. On Friday, openDemocracy reported that Egypt has hired Hill+Knowlton, a PR giant whose clients include colossal fossils ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, and Saudi Aramco, to manage communications.

“The COP presidency should use a PR firm committed to achieving the goals of the Paris agreement,” said Kathy Mulvey, accountability campaign director at the Union of Concerned Scientists. “All bad actors involved in climate deception—including the PR industry—must be held accountable.”

Hill+Knowlton, she added, has a “shameful track record of spreading disinformation” on behalf of oil companies.

Last week, as well, Megatrends Afrika published a heavily-annotated exposé on the role of Egypt’s General Intelligence Service (GIS) in orchestrating the COP.

“Officially, the GIS will not play a role in the climate conference,” the news story states. “Behind the scenes, however, the GIS is pulling the strings. This is suggested by reports from various non-governmental organizations, which criticize the Egyptian government’s considerable harassment of their peers. Voices critical of the government were deliberately excluded from the conference,” and the conference centre where the COP will take place apparently belongs to the GIS.

Megatrends Afrika connects its concerns to recent media trends under the “authoritarian leadership” of President Abdel Fatah al-Sisi.

“In recent years, the GIS has successively taken control over various private media companies in the country and merged them under the holding company United Media Services (UMS),” Megatrends writes. “Through these outlets, the foreign intelligence service exerts significant influence over domestic reporting, also in the context of the climate conference. For example, in such media, human rights organizations including Human Rights Watch are denigrated as the mouthpieces of terrorists.”

The COP represents “a welcome opportunity for the GIS to further expand its media activities,” with financial support from Saudi Arabia, Megatrends states.

This article is republished from The Energy Mix. Read the original article.