On a cold and blustery day in March 2011, a massive, 80-metre-tall wind turbine at Iberdrola’s 149megawatt Rugby Wind Power Project in North Dakota suffered a catastrophic mechanical failure. Some bolts let go and the entire rotor assembly, along with all three blades, crashed to the ground. No one was hurt; there was no contamination, no cascading grid impacts and no lasting effect on the local economy. The other 70 turbines were shut down immediately; technicians inspected each of their roughly 3,360 critical bolts, replaced just seven bolts on four machines as a precaution, and had the full wind farm back in service within a week. The accident cost a few million dollars, an amount judged immaterial to the Iberdrola Group, whose diversified portfolio of generating assets dominated by renewables turned in a net profit of about US$4 billion that year.

At almost the same time, thousands of kilometres away, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear station failed in ways that still reverberate. Safety systems that were supposed to be independent failed together, leading to fuel melting and hydrogen explosions that destroyed four reactor units and released radioactivity to the air and ocean. It took months to stabilize the damaged reactors and bring them to a cold shutdown, and site remediation will continue for decades. The cascading consequences crippled Japan’s nuclear sector and generated economic, social and environmental damage far beyond the plant fence line. The cost of the accident is incalculable but runs into the hundreds of billions of dollars. It ruined the Tokyo Electric Power Company.

The contrast is not just about two technologies; it is about two ways of structuring risk. The Rugby turbine failure remained a localized engineering incident, largely managed internally by the project owner and manufacturer. Fukushima produced losses at least five orders of magnitude larger than a single windturbine crash, and it did so in a way that pushed financial burdens across the Japanese state, its taxpayers and future generations.

Energy systems like the one in Fukushima, built around a small number of very large, colocated units, running near full output with critical safety functions sharing common failure modes, and overseen by a regulatory culture that discounts lowprobability, highimpact events, is not just vulnerable. It is a catastrophe waiting to happen.

Biomimicry – the practice of learning from and emulating nature’s strategies – offers a vocabulary for understanding why. Nature has had billions of years to experiment under uncertainty. Complex living systems endure not because they avoid shocks, but because they are built to absorb them. In healthy ecosystems, risk is not eliminated; it is distributed, diversified, buffered and constantly managed. Redundancy, modularity, diversity, continuous feedback and slack capacity are not poetic metaphors but survival rules. Those same rules can be applied directly to how energy systems are planned, financed and operated.

Nature has had billions of years to experiment under uncertainty. Complex living systems endure not because they avoid shocks, but because they are built to absorb them.

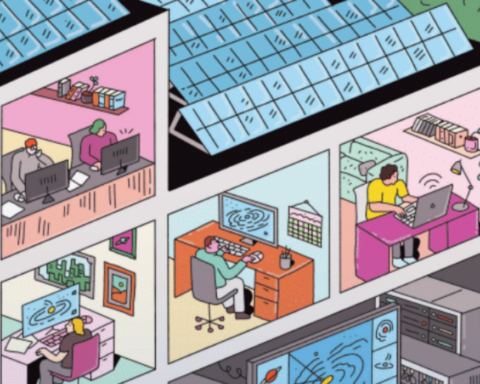

For a decarbonized power system, this means grids and portfolios that can lose parts without losing the whole; that can reconfigure under stress; that favour many small, distributed investments over a few gigantic, centralized bets; and that can learn and adapt quickly from minor failures rather than waiting for rare, systemwide disasters. It also means staying within biophysical boundaries – emissions budgets, land and water limits, ecological constraints – that make life and prosperity possible in the first place. In that sense, the distinction between nuclear and renewables is not just about carbon intensity or levellized cost; it is about whether a technology encourages risk to be concentrated or distributed.

Nuclear power, by virtue of its scale, complexity, slow learning curves, security requirements and tailrisk profile (or rare disasters), tends naturally to become centralized. It also has a very low tolerance for failure. Wind and solar, with their modular hardware, high unit counts and rapid learning cycles, tend to embed values of decentralization, resilience and acceptance of small, noncatastrophic failures as a price of innovation.

If the goal is resilience and affordability in an era of climate chaos, then energy systems can no longer be imagined as just a string of independent megaprojects. Nature shows us how to structure risk so that failures are local, bounded and recoverable. Yet our most sophisticated infrastructures still concentrate risk in a handful of giant nodes. Energy technologies can be more or less safe, but the deeper question is whether the systems we build behave more like living ecosystems or more like brittle machines.

A living system is diversified, adaptive, repairable and resilient. That is the kind of grid we need now, and it is the one that becomes possible when engineers, planners, regulators and investors start taking their cues from nature.

Ralph Torrie is director of research at Corporate Knights.

The Weekly Roundup

Get all our stories in one place, every Wednesday at noon EST.