It was a week that rocked Latin America and raised concerns over how the United States intends to throw its weight around the global playground. The U.S. military operation that extracted, or “kidnapped,” Venezuela’s authoritarian president, Nicolás Maduro, from Caracas has marked a profound shift in geopolitics that extends far beyond the South American nation’s borders.

In the aftermath, demonstrations both in favour of and against the U.S. action have cropped up around the world.

Glinelide Aponte was sandwiched among thousands of Venezuelans in Argentina’s capital of Buenos Aires on January 3, celebrating the ouster of a man they blamed for forcing them out of their homeland. Some eight million Venezuelans, or one-quarter of the population, are estimated to have fled their country since 2014, according to UNHCR, the United Nations Refugee Agency, fanning across the world in search of a better life and upending regional immigration politics.

Aponte, 28, left seven years ago. She first took a bus to Lima with friends, then travelled on to Buenos Aires, where she has built a life, working and in a relationship. Her decision to leave was largely based on chronic shortages that made it impossible to plan for the future. “There was nothing, from basic supplies, food, even transport to be able to go to university,” Aponte says. The news of Maduro’s removal was “one of the happiest days of my life,” even if she admits to confusion over what could happen next. “We were in a very difficult position,” she says, one that “can’t get worse.”

While the legitimacy and legality of the U.S. stealth attack on Venezuela in the early-morning hours of January 3 are deeply contested, the possible ripple effects extend far beyond the courts. The United States appears to have abandoned any nominal respect for sovereignty, particularly where its energy ambitions lie, and unlike with previous regime changes in Latin America, its intentions have been crystal clear. “We are going to run the country until such time that we can do a safe, proper and judicious transition,” President Donald Trump said in the hours after the attack. Maduro and his wife, Cilia Flores, are being held in New York City and have been formally charged in a narco-terrorism conspiracy that includes the importation of cocaine to the United States. They have both declared their innocence.

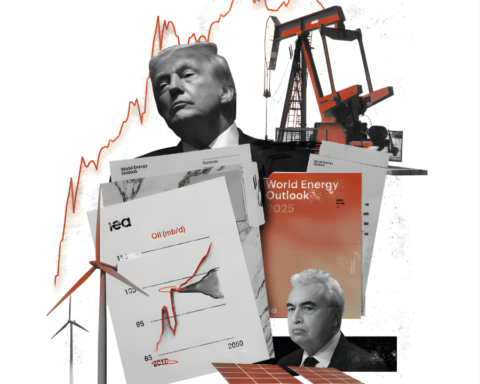

Indeed, beyond the shock and awe, U.S. imperialism has, arguably, never been so transparent. Trump has already taken steps to claim what he declared was a prime motivation: Venezuelan oil, which had suffered a severe decline in recent years, because of mismanagement and also U.S. sanctions that crippled Venezuela’s petroleum-dependent economy.

Trump’s administration has elected to keep the rest of the regime established by Maduro’s predecessor, the populist socialist Hugo Chávez, in place and work with Maduro’s vice president, Delcy Rodríguez, who has been sworn in as interim president. On Monday, Trump declared himself the “acting president of Venezuela” in a post on his social media site Truth Social. The Trump administration made the surprising choice of backing Rodríguez as interim leader, rather than María Corina Machado, the leader of the right-wing opposition whose party is widely seen as having won the 2024 elections in Venezuela and who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to return democracy to her home country. Last week, Machado said she would share her Nobel Prize with Trump, something the committee that awards the prize says she is not able to do.

Legal experts around the world have condemned the U.S. intervention. “I remain deeply concerned that rules of international law have not been respected with regard to the 3 January military action,” UN Secretary-General António Guterres said before a meeting of the Security Council last week. “The [UN] Charter enshrines the prohibition of the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”

The response from the international community has been divided, with countries in Latin America such as Brazil, Colombia and Mexico roundly criticizing the unilateral move, along with Russia and China. But other powers, including the European Union and Canada, refrained from explicitly saying the United States went too far, focusing instead on their long-time refusal to recognize Maduro as Venezuela’s legitimate leader following electoral fraud and well-documented human rights abuses.

“The European Union calls for calm and restraint by all actors, to avoid escalation and to ensure a peaceful solution to the crisis,” a statement signed by 26 EU member states, not including Hungary, declared.

But the U.S. action is about more than a dictator. It is the starkest evidence of a new era in foreign policy that reactivates the Monroe Doctrine, an 1823 declaration by the United States that sought to assert dominance in the Western Hemisphere. The reinterpretation has been dubbed the “Donroe” doctrine, and Trump has since made controversial insinuations of possible interventions in Colombia and Mexico. Denmark’s Arctic territory of Greenland is once again in his crosshairs. “One way or another, we’re going to have Greenland,” he said over the weekend. “If we don’t take Greenland, Russia or China will.”

The geopolitical chess board is shaky. What the U.S. intervention in Venezuela means for energy policy is still unclear. U.S. forces have intercepted five oil tankers since Maduro was removed, and Trump has said that Venezuela will be “turning over” up to 50 million barrels of oil to the United States. It stands to reason that Canada, as a primary exporter of oil to the United States, will bear some impact, although the timeline for ramping up production in Venezuela is unclear, with analysts suggesting it could take years.

But there are other signals of important changes, namely the release of more than 100 political prisoners, which by some estimates represents about 10% of those incarcerated under Maduro’s regime.

The Weekly Roundup

Get all our stories in one place, every Wednesday at noon EST.