For decades, an 11-acre parcel of land outside Antigonish, Nova Scotia, served as the collection point for municipal garbage. After it shuttered in the 1970s, the plot, located on a quiet, wooded road near the town, languished.

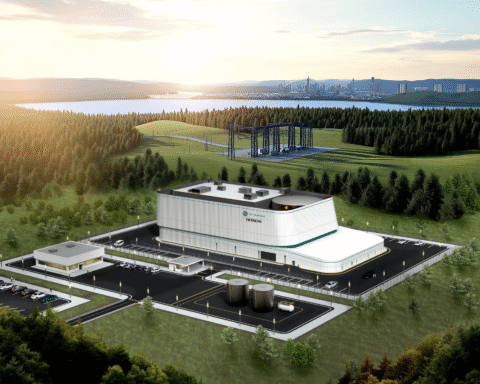

Then, an unexpected opportunity to reclaim the land presented itself. In 2020, the municipally owned company that runs Antigonish’s utility and those of two other Nova Scotia towns set out to develop three community solar projects for each of the three towns it manages. The residents of Antigonish hope to make their town one of Canada’s first net-zero communities, including with community solar. But to get the project off the ground, they needed space – and the idea of a solar farm offered the chance to give the former landfill new life.

Since January, the Antigonish Community Solar Garden has been producing 1.65 megawatts of power for residents and businesses, providing roughly 4% of the town’s energy needs (another 40% comes from wind). It’s just one of dozens of projects across Canada that are using brownfield sites – land contaminated by past commercial or industry use, such as landfills, oil refineries and gas stations – to host solar farms.

In a net-zero world, vast amounts of power will need to come from wind and sun. But real estate is a bottleneck: to phase out oil and gas, panels and turbines need somewhere to go. Ideally, this land needs to be located near existing roads, communities and grid infrastructure – exactly the kind of land that’s in demand for other uses.

European non-profit the Renewables Grid Initiative estimates that to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050, the EU will need to allocate roughly 100,000 square kilometres to renewable-energy generation and grid expansion – an area roughly the size of Iceland. A 2021 paper published in Nature Scientific Reports estimated that to provide 25% to 80% of the electricity mix in some parts of the globe, solar energy would need 0.5% to 5% of total land in those areas. And that has communities like Antigonish going to the old dump for spare land.

Such projects hold the promise of repurposing lands that meet many of the requirements for renewable power generation, while not being suitable for any other purpose. But as the Antigonish experience shows, they can also be unexpectedly complex, with issues ranging from unstable footing to unhappy residents. “It’s like buying an old house that you’re going to renovate . . . You open the floor and you’ve found that, you’ve found this,” says Antigonish Mayor Sean Cameron. “That’s the kind of the thing we fell into with this one.”

These are the kind of complexities that have turned brownfields into an albatross around the neck of many communities, as governments struggle to deal with the toxic legacy of contaminated sites; in Canada alone, there are tens of thousands of brownfield sites, and the cost of cleaning them up can exceed the value of the land. But with land at an increasing premium and the deadline to shift off fossil fuels approaching, interest in repurposing those sites for renewable energy is growing. Has a brighter future for brownfields arrived?

A tailor-made solution

The concept of “brightfields” – as brownfields used to generate renewable power are known – originates in the United States. In 1999, the U.S. Department of Energy launched the Brightfields Initiative, aimed at helping communities turn former toxic sites into solar energy producers. By 2010, a seminal study in Michigan found that existing brownfield sites could provide 43% of the state’s residential electricity consumption. “They said, for sites that are either heavily contaminated or the market can’t address them, why don’t we put solar panels on them as an interim use or permanent use,” says Christopher de Sousa, professor in the School of Urban and Regional Planning at Toronto Metropolitan University and head of a research lab looking at brownfield reclamation.

De Sousa says these early initiatives established a blueprint, and not just through large-scale efforts; small projects, such as the 3.7-acre, 425-kilowatt solar garden built at the site of a former gas works in Brockton, Massachusetts, also helped set a new paradigm. Nearly every closed landfill in Massachusetts is now a brightfield, and there are more than 600 brightfield projects scattered across the United States. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency continues to run a program called RE-Powering America’s Land, promoting the redevelopment of brownfields for renewable energy.

Solar is one of the most approachable uses for brownfields; unlike wind turbines, panels don’t require digging deep into the ground, which could disturb hazardous material. Solar farms also don’t expose people to contaminants the way that residential developments or parks would, de Sousa says.

But while Canada has a federal strategy for contaminated sites, the repurposing of brownfield sites for renewable energy has lagged behind other jurisdictions. A 2016 paper by de Sousa estimated that there were only about 30 brightfields in the country.

Meggen Janes, executive director of the Canadian Brownfields Network, says that’s changed in the last five years, as the conversation about converting brownfields to brightfield projects has accelerated, putting sites that can’t easily be developed for housing or parkland to use.

This includes an initiative in Alberta, where a company called RenuWell Energy Solutions has conducted a pilot project to turn abandoned wells and oil and gas infrastructure on farmland in the southern half of the province into a 1.45-megawatt solar project across two sites. Because the approach uses existing roads and power lines, it can offer power from small-scale solar at close to the cost of very large sites. Meanwhile, it addresses an existing environmental liability by mitigating the expensive process of closing down old wells; much of the expense of remediating a well site is from removing access roads and revegetating the area, neither of which are required if it’s used for solar.

This significantly reduced the cleanup bill facing the Orphan Well Association (whose coffers are significantly short of the money needed for well cleanups): costs were 80% less than they would otherwise have been, says Keith Hirsche, founder and president of RenuWell. Hirsche says using brownfields for solar is not only cost-effective; it also reduces carbon emissions. “You’re basically [removing] both the energy that it would take to clean that stuff completely up, and then also the energy it would take to put new stuff down . . . across the board, I think it’s a helpful solution.”

RenuWell is now looking to scale up, including with provincial support to build a 20-site grid-scale pilot for solar plus storage, though the company is facing inertia caused by political divides and entrenched interests, including the legacy energy sector. Still, with abandoned oil and gas infrastructure covering at least 340,000 acres in the province, Hirsche says there’s significant room to grow. “This only can impact 10% of [sites] maybe, but . . . if you converted 10% of these abandoned gas sites, you meet almost the projected growth of power demand for the next 10 years in Alberta.”

Solar energy is good for the planet, but it could be bad for birds

No smooth sailing

In Antigonish, the goal for brownfields is more modest.

Unlike most communities in the province, Antigonish owns its own electrical utility. This allows the community more autonomy in setting clean energy targets, and the town has the ambitious goal of producing 80% of its electricity from renewable sources by 2030. To help with this, the town’s plan was initially to build a 2.1-megawatt solar garden that would expand access to solar for the town’s residents, including those without the means for their own rooftop solar.

But landfills are among the most challenging types of brownfield sites to develop, and that proved true in Antigonish’s case as well. Because the site was a former landfill, it didn’t provide stable footing, which meant less of the available area was suitable for panels than planned. The town then had to clear some forest to create more space, causing runoff and increasing tensions with some residents. Grid connection was also pricey. The dumpsite was outside of the town, so the municipality had to pay to run power lines to the site, which cost around half a million dollars. “There was a bunch of issues that kind of snowballed,” Mayor Cameron says.

In the end, the solar garden took two years and $2 million more than anticipated – but Cameron says he would still consider brightfield projects in the future, especially on a less complicated site. “If we get more funding, I would certainly explore another solar garden.”

Remediation and reparation

These kinds of issues can drive developers away from brownfield sites. But brightfield projects have an additional benefit working in their favour: righting wrongs done to marginalized communities.

In 2019, the Tŝilhqot’in Nation celebrated the opening of a 1.5-gigawatt solar farm at the site of a former sawmill. It is the first 100% Indigenous-owned solar farm in Canada, on the first such timber mill to be redeveloped as a solar farm.

Since then, other Indigenous communities have seized similar opportunities, including in the Northwest Territories, where an Indigenous-owned business has developed a one-megawatt solar farm on a former brownfield site in Inuvik, and in Nova Scotia, where two Mi’kmaq Nations have partnered with a local municipality to develop a seven-megawatt solar garden at the site of a capped landfill.

Christopher de Sousa says that because of the legacy of environmental racism, where polluting activities were located near marginalized communities, many brownfield sites are now located on Indigenous land. In some parts of the country, Indigenous communities are also more reliant on diesel and other forms of fuel, making renewable energy on brownfields especially appealing.

For these communities, de Sousa says, brightfields offer the possibility of remediating contaminated sites, switching to cleaner energy and creating jobs and revenue – projects that have the potential to be “win-win-win.”

Incentives incoming

Across the country, advocates say the primary barrier to accessing these wins is financial. “You know, why am I going to invest time and effort into developing a site that might take . . . a million dollars to clean up,” de Sousa says, “when right next door I have a clean one?”

This is less an issue for large centres, where land is at enough of a premium that developing a brownfield is worth the cost and risk. Meggen Janes says that small communities, by contrast, often struggle to find the resources to deal with brownfield sites. “I’ve talked with many mayors across the country, and they’re trying to find programs . . . that would support their initiatives.”

Still, local governments can also be leaders; in Calgary, where two solar farms recently opened on contaminated sites that had been used by a fertilizer company, the city has created a program to incentivize brownfield redevelopment for wind and solar with a reduction in municipal taxes. And in Nova Scotia, a new provincial program that aims to create 100 megawatts of community solar is prioritizing projects located on brownfields.

Ultimately, Janes says, the potential of brownfield sites is vast. In Europe and North America, there are an estimated 3.5 million brownfield sites, making a significant source of developable land.

In this respect, crises can serve a useful function. The affordable-housing crisis has prompted some Canadian municipalities to focus on brownfield sites for affordable housing. After another summer of droughts, fires and floods, the climate crisis may serve as the motivator to turn polluted sites into the engines of a more sustainable future.

Moira Donovan is an independent journalist based in Nova Scotia, specializing in the environment and climate change.