In Pakistan, solar panels are worth their weight in gold.

Traditionally, Pakistani women have accumulated jewellery, particularly gold jewellery, as an investment – ornate accoutrements that double as savings accounts for families and may be passed on to future generations. Lately, as an electricity revolution takes hold, women are trading some of that jewellery for a different kind of bling, using the proceeds to finance rooftop solar panels.

“People are understanding it is a very good investment,” says entrepreneur Waqas Moosa, a member of the Pakistan Solar Association.

It’s one sign of the solar boom that is happening in the fifth-most populous country in the world. Across industry and class, solar has planted seeds and is flourishing on Pakistan’s rooftops. Turnkey homes now include solar panels as if they were fridges. Young people save up for photovoltaic kits before they buy cars. There are hundreds of solar importers and thousands of installers. Charitable organizations that run orphanages and schools now also provide loans for small solar solutions.

We’ve almost doubled our business every two to three years. It’s been very fast growth.

Waqas Moosa, CEO, Hadron Solar

The speed and scale of Pakistan’s solar incursion is, as many observers put it, the result of a perfect storm of factors, including a society already used to fending for itself on energy as a result of an unreliable power grid that was prone to brownouts; International Monetary Fund–driven austerity measures that, along with the Russian invasion of Ukraine, pushed up the price of conventional electricity; and a glut of cheap solar panels available from its industrious neighbour, China.

“Sometimes when the markets align and people decide that they want to go a certain route, things can happen,” says Muhammad Mustafa Amjad, program director at Renewables First, a Pakistan-based think tank.

A thriving new energy economy

Solar uptick is happening fast across significant parts of the Global South. Nations that face a similar set of circumstances, such as poor access to energy and suffocating electricity prices, are being enticed by the economics of increasingly affordable Chinese solar panels and free access to the sun.

A recent report by energy think tank Ember found evidence of a nascent solar boom in Africa. Imports from China rose 60% over 12 months, with 20 countries in Africa posting record panel imports, led by Nigeria, which imported 1,500 megawatts in the 12 months preceding June 2025. But that is dwarfed by the growth in Pakistan, which imported more solar panels than all of Africa during the same time period, despite having one-sixth of the population.

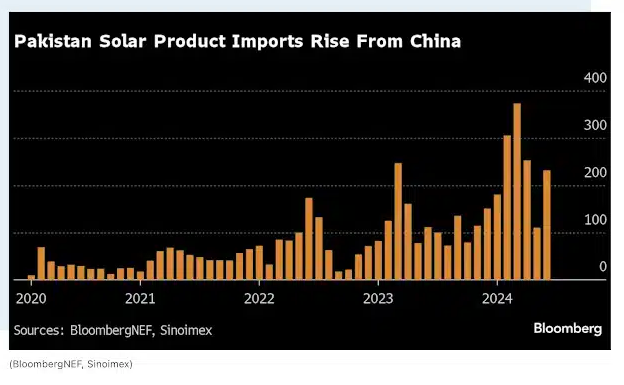

Over the span of four years, Pakistan bought US$4.1 billion worth of solar panels, according to Bloomberg. In 2024 alone, the nation doubled the gigawatts of panels it brought in. The statistics underscore a fundamental shift. The energy transition in this country is very much people-led, Amjad says. He co-founded Renewables First in 2021 as a way to help understand the energy transition from a Global South perspective. “A lot of policies are often dictated by the IMF and the World Bank, and they do not necessarily result in good things on the ground,” he says.

The availability of Chinese-made solar panels has been key to fast adoption. In 2024, the average price of a solar panel plummeted from 32 cents per watt to 17 cents, according to an analysis conducted by Renewables First. The solar-panel market turned into a lucrative money-making venture for traders, middle players and investors, which shifted economic activity from the struggling real estate sector to renewables, the think tank observed.

“We’ve almost doubled our business every two to three years; it’s been very fast growth,” Moosa says on a phone call from Lahore, where the company that he co-founded in 2014, Hadron Solar, has benefited from Pakistan’s solar surge. Some of the rapid growth has been spurred on by government incentives, such as tax breaks and more affordable financing loans for residential buyers.

The Pakistan Solar Association has between 400 and 500 members, Moosa says, which are mid- to large-sized companies that are typically in the import and distribution business. He estimates that there are tens of thousands of other people who are in the installation business.

Hadron mainly sells directly to users, whether they be residential, commercial or rural. More recently, it began selling component parts to smaller providers and installers, a sign of the pyramidal growth of solar, which started with those with the disposable income to install large units on their roofs and has now spread across a wider income strata. In villages or less affluent communities, you may find smaller kits on balconies.

A fundamental shift in the energy user – from a consumer to a “prosumer,” which is what the industry calls someone who buys higher-quality electronic products – has helped drive this explosive solar growth. A 2015 change to the national regulations allowed users to install small-scale renewable-energy systems such as solar and made it easier for people to generate their own energy without having to jump through bureaucratic hoops. As solar-panel prices plummeted around the world – by 42% in 2023 alone – the cost of grid electricity soared in Pakistan. Now, typical solar installations can break even in two to four years.

But it’s not just residential users who are turning to solar: the business and farming sectors are also making the shift. Agriculture accounts for one-quarter of Pakistan’s gross domestic product, and half of its labour force. It relies heavily on tube wells to irrigate predominantly dry land. Various initiatives from the federal and provincial governments aim to solarize swaths of the tube wells, spurred on by both a jump in diesel prices and spikes in electricity tariffs, making solar energy “not just an environmentally friendly option, but an economic necessity for many farmers,” researchers from Renewables First note.

“The Stone Age did not finish because we ran out of stone, the Iron Age did not finish because we ran out of iron, and the oil age is not going to finish because we ran out of oil or fossil fuels,” Moosa says. “It basically ends when the new technology is ready to take the throne. And today, renewables are in the right place.”

Lessons for the Global South

The sheer speed of change has meant that Pakistan has had to transition “on the go,” which is “a characteristic that is present in a lot of Global South countries,” Moosa notes.

Along the way, difficulties have cropped up. Chief among them is the tug-of-war between the centralized energy company and the decentralized push to democratize access to energy. The traditional dynamic of energy distribution in which there is one provider and multiple buyers has changed, as people gain the ability to generate their own. This is especially relevant in countries of the Global South that already grappled with energy insecurity, such as Nigeria, where large chunks of the country did not have access to reliable power.

RELATED

Novel project in California has solar panels stretching across water canals

Solar energy is good for the planet, but it could be bad for birds

The rooftop solar revolution is accelerating — and all eyes are on Asia

Rising energy rates have created a feedback loop in Pakistan: in recent years, thousands of people have taken to the streets to protest ballooning utility bills, leading some to turn to solar as an alternative, in turn destabilizing the already shaky finances of the central distributor. The impact is disproportionately felt by people who still cannot afford the upfront costs of solar panels, despite the various mechanisms available to lower the price.

Pakistan is also seeing the effects of the “duck curve,” the name given to the graph that shows the rise and fall of electricity supply and demand fuelled by solar energy. In the middle of the day, energy demand on the grid slumps because people turn to their own supply of solar, and then it soars in the afternoon and evening as that supply drops.

While the solar boom in Pakistan is happening both off- and on-grid – meaning that some users have been selling power back to the central system – the sheer number of people turning to solar and then needing to jump on the grid when the sun sets has presented a whole set of problems that strains the grid’s capacity.

“Obviously there is a problem,” Moosa says. “I think the battery is going to play a very big role, and where the battery falls – either ahead of the meter or behind the meter – is going to have a big impact on how the grid of the future is going to look.” Meaning, will the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) continue to incentivize consumers to sell their power to the central grid, and store it in community battery packs, or will it alienate them and push them to buy personal battery packs, or off-grid battery solutions?

Currently, NEPRA is revising its net metering system and has proposed reducing the rate at which it buys power back from consumers. “We anticipate that a lot of consumers will start choosing to go for batteries,” Moosa says, which could have profound implications for the relevance and sustainability of the central grid.

“I think that is where Pakistan is going to add value,” Moosa says, for the rest of the world, “because we’ve already reached the point where we have to make decisions.”

Natalie Alcoba is a Buenos Aires–based journalist and senior editor at Corporate Knights.

The Weekly Roundup

Get all our stories in one place, every Wednesday at noon EST.