In the constellation of renewable-energy technologies that the United States has sought to deploy in order to battle climate change, offshore wind has had perhaps the rockiest path in recent years. In 2023, high interest rates and the global supply chain shocks brought a slew of developments across the country to an end. Even without these macroeconomic obstacles, offshore wind is a mammoth undertaking. It’s difficult to overstate the sheer scale of the endeavour that is the construction of an offshore wind farm. The largest turbines are the length of football fields and require specially built ships to transport them.

If offshore wind can take off anywhere, it’s New England, whose waters provide the highest wind-capacity factor (the amount of energy a turbine can produce over time) in the continental United States. In October 2023, three states – Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts – signed a first-of-its-kind multistate procurement agreement to collectively share the costs and benefits of adding new offshore wind generation. The vision behind the plan was to reduce the cost per megawatt of the electricity generated. So far, the results of this deal have been uneven: two of the states have selected developers for new projects, but Connecticut has not.

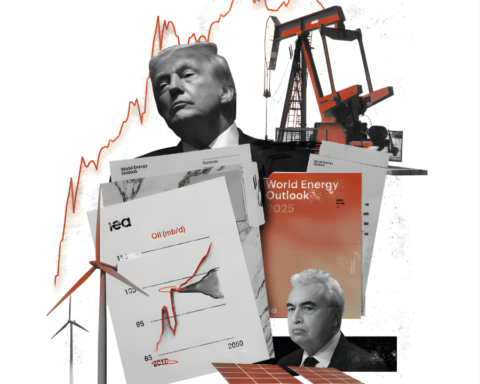

But the election of Donald Trump could arrest the region’s momentum before it has had a genuine chance to take off. Trump has made a point of demonizing the technology (“I hate wind,” he is reported to have bluntly told oil and gas executives at a fundraiser) and has repeatedly made false claims about its impact on wildlife. At a campaign rally in May, Trump pledged to ensure that offshore wind projects come to a halt “on day one” of his second term. That could have been mere campaign-trail bluster, but of the clean energy technologies that the Inflation Reduction Act flooded money into, offshore wind is perhaps the most vulnerable to an unfriendly president.

In addition to the political calculations, the question of whether this coalition of states can build and deploy the offshore wind projects amounts to a test of U.S. industrial capacity. To bolster the case to state governments for doubling down, there is growing support in the region from a somewhat unlikely corner: New England’s industrial unions, a group of whom published a report last week, in partnership with the Climate Jobs National Resource Center, outlining an ambitious vision for supplying the region with not only offshore wind turbines but a locally based industrial manufacturing base to support it.

“This entire industry that we’re trying to get launched has thousands and thousands of job opportunities, whether you’re talking about port construction or port renovations to make sure that offshore wind can be developed at a larger scale, whether you’re talking about component manufacturing, whether you’re talking about vessel manufacturing – all of these things are going to be critically important,” said Patrick Crowley, the president of the Rhode Island AFL-CIO. “We’re not talking about just individual energy projects. We’re talking about developing an entire energy industry and everything that goes into it.”

At a launch event for the report on Tuesday, Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey said the unions’ proposal “supports the region’s continued progress building a robust, worker-centred offshore wind industry. This is an incredible opportunity to lower costs and create good jobs for working people in our region while achieving energy independence, cleaner air and a climate-resilient future.”

There are just three operational wind farms in the country. According to Timothy Fox, managing director of ClearView Energy Partners, a Washington research firm, those power stations generate only about 200 megawatts of electricity – a fraction of the 50 gigawatts (50,000 megawatts) that states have committed to building, if their renewable-energy targets are tallied together. The federal government has approved leases for wind projects that would generate 15 gigawatts of energy, and the onus now is on states to build the turbines – and to require their utility companies to buy electricity from it.

The unions’ report calls for building nine gigawatts of offshore wind energy in the waters off Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts by 2030 – scaling up to 30 gigawatts by 2040 and 60 gigawatts by 2050.

To meet these goals, the report suggests that states employ “a climate and jobs strategy, built around new investments, active government facilitation of industry growth, and reliance on a skilled union workforce.” It argues that offshore wind’s success will depend on a combination of investment in the region’s ports, regionally based component manufacturing, domestically built installation vessels, coordinated transmission planning between the states involved, and strong labour standards.

To maximize the benefits of offshore wind, the three states will need to coordinate their efforts on a range of tasks, from building transmission lines (which often requires tricky interstate negotiations) to collective procurement – and that’s one area where, Crowley argued, unions are uniquely positioned to help, by leveraging the power of their mass membership across state borders and political influence in Democratic state governments.

“There isn’t another organization except the labour movement that has a presence in all of these states in such a way that, if my counterpart in New York, Vinny Alvarez, calls up and says, ‘Patrick, there’s a hearing at the Rhode Island Coastal Resource Management Council about a transmission line for a project that we’re doing. Can you get a couple of people to go testify?’ – ‘Absolutely.’ And we’re there within hours,” Crowley said.

As an example of this leadership in action, Crowley cited the tri-state procurement agreement, which he described as “a paradigm shift in thinking that I don’t think would be possible except for the labour movement pushing this agenda.” He cast the agreement as a departure from the standard practice by which states attract investment and industry: “All of these states compete with each other when it comes to the economic marketplace,” Crowley said.

“We’re dealing with something right here in Rhode Island,” he continued. “One of our major employers, Hasbro Toys, is being courted by Massachusetts to move up from Providence up to Cambridge to move their headquarters there; we might lose a thousand jobs and Massachusetts will gain them. We’re not going to stop that kind of competition. But when we can eliminate it from the beginning, at the beginning of this industry – oh my god. This is a total economic paradigm shift that I don’t think folks have fully digested yet.”

But to get the unions’ vision past the finish line, especially against the headwinds of an unfriendly federal government, will be no easy feat – and crucially depends on private investment. This is also somewhere that Crowley believes unions can play a role. “The labour movement, through our pension funds, has access to a vast amount of investable capital,” he said. “And maybe what we’ve got to do is be creative about how we can leverage the funds that are in our pension systems, both private and public sector, to be a funding mechanism for developing this industry.”

Jeff Plaisted, an electrician in Massachusetts, worked on the crew that laid six miles of cable from the Vineyard Wind wind farm off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard to a power substation on Cape Cod, passing under the streets of the town of Hyannis. “Since the Vineyard Wind project broke ground, and that project really got off the ground,” Plaisted said, “we had full employment in Local 223” – the southeastern Massachusetts branch of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, of which Plaisted is now the business agent and organizer of membership development.

The project brought an unusual amount of work to the region. “We had travellers from other jurisdictions coming and signing our book to work in our jurisdiction because we needed the manpower from outside what we had to offer just to fill the job calls,” Plaisted said. “That substation in Hyannis had 70 to 80 electricians on, and we very rarely see jobs in our jurisdiction that require that kind of manpower.”

RELATED:

Wind and solar energy surge past fossil fuels for first time in Europe

Clean energy will draw in $2 trillion in investments this year, setting new records

As bombs drop, Ukraine energy company opens a new wind farm

When Plaisted began working on the Vineyard Wind project, “what surprised me personally is the magnitude, the size of the turbines themselves,” he said. The job itself was a far cry from the normal work of a union electrician. “You’re not just stripping wires. The splicing operations, everything involved with it is highly skilled and very technical. The guys that are offshore, they’re taking a boat to work, five-plus hours offshore.”

Plaisted is part of a growing number of union leaders who have spent the Biden years making the case that organized labour will need to play a starring role in the nationwide transition away from fossil fuels – not just in offshore wind, but in the vast landscape of industrial work, from electric vehicles to transmission buildout, that the transition will require.

Plaisted said that trade unions are reckoning with the fact that “climate change, it’s not a theory. It’s an actual thing; it’s not a belief system. It’s an issue that we’re going to have to deal with. If the goal is to get off fossil fuels, then everything should be brought to the table – solar, wind, battery. And union labour is the way to make those things happen,” he said.

Their efforts were bolstered in some respects by Biden’s attachment of labour-friendly requirements to many of the grants for clean energy, as well as an unusually friendly National Labor Relations Board. But unions now face a set of strategic decisions around how to engage with a Republican administration expected to be far less friendly to organized labour. “We’re at a crossroads,” said Keith Brothers, business manager of the Connecticut Laborers’ District Council.

Under a new Trump administration, unions’ efforts may be directed more locally. “We’ll fight in Congress and in the halls of agencies,” said Jason Walsh, executive director of the Bluegreen Alliance, a coalition of unions and environmental organizations, in an interview before the election. “But I would expect our members and the members of our partners to be in the streets more, in the fullest sense of that term, and on the shop floor, and working much more in state capitals, while not taking our eyes off of all the dangerous actions that a Trump administration would pursue.”

This article originally appeared in Grist. It has been edited to conform with Corporate Knights style. Grist is a non-profit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at grist.org.