It is quiet and lonely on the mountainous range of Argentina’s Catamarca Province, where llama-like vicuña graze and stocky shrubs steel themselves against the windswept altitude of the grassland known as the puna.

But do not be fooled: geopolitical tectonic shifts are happening here, on the axis of the so-called lithium triangle, where roughly 60% of the green energy transition’s most coveted resource is stored.

Lithium has never been more in demand. The precious metal that powers batteries – everything from cellphones and laptops to solar panels and electric vehicles – is now woven into the tapestry of moves and countermoves by the world’s largest powers, as they acquire supplies and set up production lines.

By some estimates, global demand for lithium will grow 40-fold by 2040, mostly for EVs and renewable-energy storage. As a result, the world’s eyes are fixed on the protagonists of the lithium triangle: Argentina, Chile and Bolivia, whose high-altitude salt-flat brines are estimated to contain 52 million tonnes of lithium.

China, where most of the raw materials for batteries are processed, has already staked a dominant claim in all three countries, investing US$2.7 billion in Argentina alone, where it will produce more than a quarter of that country’s lithium by 2030. Western companies are also playing a growing role, while the United States’ historic climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act, is sure to spur more action.

As the “white gold” rush ramps up, each lithium-triangle country offers a case study in how, and perhaps how not, to regulate a coveted mineral critical to the green transition, with high stakes all around.

“In theory, we’re doing this for a better environment and a better world, and – in theory – the whole value chain should have that goal in mind,” says Patricia Vásquez, an energy expert and global fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. “That’s what the energy transition is all about.”

And yet, growing resistance on the ground warns of a clean energy transition that is masking neocolonial practices of extraction and leaving local communities by the wayside.

Lithium, three ways

As far as supply is concerned, there is lots of it. But not all lithium is created equal. The highest quality comes from hard rock, brine or clay. Until now, Australia has been the top lithium producer through its vast hard-rock deposits, followed by Chile, China and Argentina. The lithium in the lithium triangle is found in brine, while Mexico has clay deposits that have not yet been commercially developed. A note about terminology: resources are stockpiles of lithium that have not yet been certified for their viability, while reserves are those that are considered to be market ready.

Within the lithium triangle, Chile has the largest reserves, at 9.2-million tonnes, buried in the Atacama Desert, a mystical place in the north of the country about the size of the state of Colorado. Bolivia has the largest amount of untapped resources.

Bolivia: Playing catch-up

Between the mid-1500s and the early 1800s, a Bolivian mining town nestled into an eroded volcano was the source of 20% of the world’s silver. The precious metals from Cerro Rico – “rich mountain” – gilded Europe and bankrolled Spanish conquests but left scores of Andean people dead or destitute.

In this century, Bolivia has attempted to prevent a repeat of that foreign plundering. Under Evo Morales, a socialist who was the country’s first Indigenous president, a national lithium firm was established in 2017 to control every aspect of the value chain, including extraction, refinement, battery production and electric vehicles. Foreign companies could take part in projects, but the government would call the shots.

Vásquez says that the end result of Bolivia’s state-controlled policy is that “they have produced very little lithium, even though they have the largest resources in the world.” Large collaborations with foreign partners have faltered, and there have been technical challenges. The brine found in Bolivian salt flats has low concentrations of lithium and relatively high impurities such as magnesium, which makes it less profitable and carries other environmental costs.

But the government has stepped up its search for international partners, with President Luis Arce declaring earlier this year the “era of industrialization of Bolivian lithium” in full swing. He signed a US$1-billion agreement with three Chinese companies that will build two lithium-extraction facilities in the Uyuni and Oruro salt flats, in the country’s southwest, with a combined production capacity of 200,000 tonnes per year. In June, the government also inked agreements with a Russian state firm and another Chinese company, Citic Guoan Group.

Argentina: Open for business

Of the three countries, Argentina has been the most eager to get moving on lithium with outside investors. With tax incentives and low royalties, it is promoting an “open for business” stance that is touted by politicians at every level, and private investment has flooded in.

There are a total of 38 lithium projects in Argentina: three are operating as mines, six are under construction, and the remaining 29 are at various stages of exploration. Since 2020, lithium projects in Argentina have generated US$4.2 billion in investments, according to a report from the Wilson Center.

And while Argentina is known for its economic instability, the fact that lithium falls under the jurisdiction of provincial governments has given it the ability to create financial conditions that promise to insulate investors from some of the volatility. Argentina is expected to overtake Chile as the largest lithium producer in the region by 2030.

Chile: A new national plan

Chile is the top global producer of high-quality lithium from brines. In 2022, it accounted for 30% of all the world’s lithium production. But it’s been losing market share, generating anticipation about how it would continue to unlock this mineral resource.

Against this backdrop, Chile’s leftist president, Gabriel Boric, announced a plan this year to do mining differently, creating a new state-owned company to steer the development of lithium, a resource that has been deemed strategic since the 1970s and largely under the control of the government. Until now, Chile has granted permission to only two private lithium projects. Royalty and export prices have been on the higher end of the scale, with a small percentage – as much as 3.5% – set aside as revenue transfer to local Indigenous communities.

Under the new scheme, all new lithium contracts in Chile will be public–private partnerships under state control, and new less-contentious, water-conserving mining techniques will be favoured. While the goal is to increase lithium production by authorizing new licences, the government says it will create a protected area of salt flats that amounts to 30% of their surface area.

“We want Chile to become the world’s leading producer of lithium while protecting the biodiversity of the salt flats,” Boric said at the announcement. “This is the best chance we have at transitioning to a sustainable and developed economy.”

Troubled waters

The conventional method of getting lithium out of the salt flats involves drilling into the crust of the earth and pumping out brine into evaporation pools that are then treated with chemicals. It’s this process that is often depicted in aerial photos of giant phosphorescent squares dotting the desert landscapes of South America. The process was once promoted as inherently more sustainable than the mining of other minerals in the region, but evidence has been mounting around drained water levels in wells, rivers and wetlands, harming wildlife and local communities in a region where water is already scarce.

Mining companies have downplayed the impact of their water extraction because they say that the salty brine is not fit for human or fauna consumption and that their extraction of freshwater is minimal, but local communities that consider themselves guardians of an arid and fragile ecosystem continue to sound alarms.

“In Chile, the big critique is that there have never been proper hydrological studies to map the impact it has had on the water table, because it is so intensive on water use,” says Kirsten Francescone, assistant professor in the International Development Studies program at Trent University and former Latin America program coordinator for MiningWatch Canada.

In Argentina’s Catamarca Province, for example, small Indigenous communities in Antofagasta de la Sierra, where American mining giant Livent has been running its Fenix lithium mine for more than two decades, say a river has dried up because of overuse of water, and sheep and llamas have perished. Livent announced this year that it would expand its lithium plant, tripling production to 60,000 tonnes by 2025.

It’s often Indigenous communities that bear the brunt of the local impact because the mining occurs in territory where they live, eking out a meagre existence as farmers. Those same communities are at the forefront of protests, road blockades, lawsuits and investigations that seek to thwart lithium projects in all three countries on environmental or economic grounds.

In Bolivia in 2019, authorities cancelled a German lithium project by ACI Systems Alemania that would have secured the mineral for Germany’s electric car industry following weeks of demonstrations by residents of Potosí, who said there wasn’t enough local benefit in the deal. In Chile, Indigenous communities such as the Coyo and the Atacameña de Camar managed to block lithium mining contracts after a court ruled last year that they were not properly consulted, as is required by law. And in Argentina, a caravan of Indigenous land defenders set up camp in a plaza in front of the country’s Supreme Court, in Buenos Aires, after a violent crackdown against demonstrators opposing a law that restricted their right to protest in the northern province of Jujuy.

“We should be in the mountains with our sheep,” said Salustriana Geronimo, a grandmother, sitting inside the small makeshift hut she had crafted out of tarp. “We’re not going to allow them to just do what they want.”

Although mining companies tout the local benefits they bring to communities that are often lacking in basic infrastructure, and governments trumpet more jobs, the feeling on the ground for many is that they remain impoverished as others become wealthy. So far, being part of the green energy transition has yet to meaningfully change that.

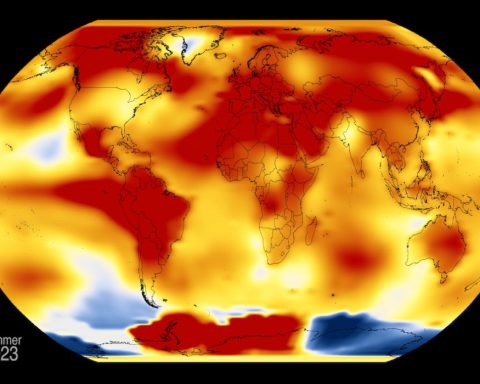

“Mining always produces winners and losers, and mining companies feed off of those divisions,” says Francescone, who doesn’t see the fundamentals of how the industry operates changing under the lithium paradigm. “What’s different about lithium mining is the buzz and the almost false hope,” she adds. “It’s very easy to tell a story that makes people feel good about it because of what the metal does. But unfortunately, we are in a moment where more mining in general, because of the climate crisis, is going to make the ecological pressures on mining regions even more salient.”

But others insist there are ways to mitigate the damage and push toward a more equitable lithium industry. A 2022 report from the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) laid out more than half a dozen recommendations it said “could help heal the ‘exhausted’ Puna de Atacama region without impeding the transition to a cleaner future for the planet.” In addition to strengthening environmental standards, boosting metal recycling and bringing in a moratorium on brine evaporation, it called on governments to go beyond revenue-sharing models with local and Indigenous communities: “While the existing benefit-sharing agreements in this region may offer a foundation for industry partnerships with communities, these agreements have thus far formalized conflict.” Advocates say that obtaining free, prior and informed consent for the use of land territory and resources from Indigenous Peoples (as Bolivia, Chile and Argentina all committed to doing when they ratified the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples) is essential for governments and companies wanting to operate sustainably and equitably – and run into less resistance.

Chile’s new lithium strategy calls for more dialogue with Indigenous communities. The Chilean government also says it will favour projects that use a new technology that extracts lithium without relying on the traditional – and environmentally contentious – evaporation process, thus reducing the amount of water that is required in an area as arid as the Atacama Desert.

“Direct lithium extraction,” using adsorption, ion exchange and other electrochemical processes, can remove lithium ions from brine water in hours, rather than months. “It reduces the times and tightens the production, like a clock, giving you a different predictability in terms of the output,” says Victor Delbuono, an economist who specializes in natural resources with Argentine NGO Fundar. Since it may rely on solar panels, rather than the sun, in the extraction process, it also requires an additional investment in renewables, he notes.

The technology will be used by some of the new Bolivian projects and has already been incorporated into one stage of Livent’s process in Argentina. The NRDC also points to the extraction of lithium from brines at geothermal power plants, a method being developed in California, Germany and England, which proponents suggest could be more sustainable.

The efforts by the Chilean government to overhaul its approach to lithium were welcomed by a wide swath of local communities, activists, environmentalists and NGOs, who nonetheless voiced several concerns, in particular that they were not consulted about the new strategy and that some of the processes appear to emulate those used by the mining industry. A statement signed by 173 individuals, organizations and Indigenous communities also described the pursuit of EVs as a “false solution to climate change that benefits the most contaminating economies on the planet, reproducing highly demanding modes of consumption to the detriment of serious climate commitments.”

Can these countries use the green revolution to break free of a pattern that dates to colonial times – that of foreign interests extracting riches and leaving little behind? Or will the green revolution further entrench it?

Whatever the approach from each country, Delbuono, the Argentine economist, says the region’s central role will not last forever.

“We’re already working on sodium batteries,” he says. “The window is small for technology.”

Natalie Alcoba is a Buenos Aires–based journalist and associate editor at Corporate Knights