It’s raining cats and dogs on Gillian Flies’s 100-acre vegetable farm, two hours north of Toronto, the week that this season’s farm workers arrive for a mandatory two-week quarantine. The certified organic acreage in the crest of the Niagara Escarpment will soon be bustling, growing salad greens for Toronto’s pandemic-strained restaurants and grocers. But right now, Flies is giving a Zoom slide show on the power of healthy soil.

“When we are facing climate chaos and these big storms come through, we can suck it in,” says Flies, referring to her soil’s ability to miraculously absorb inches of rain that turn neighbouring fields into a mud bath. A decade into working the land organically, she and her husband, like millions of farmers around the globe, were facing hotter summers, more violent storms and more erratic harvests. The former international election observers–turned farmers were looking for solutions to make their property – The New Farm – more resilient to the impacts of the changing climate. That’s when they came across a farming philosophy that turned them into soil evangelists.

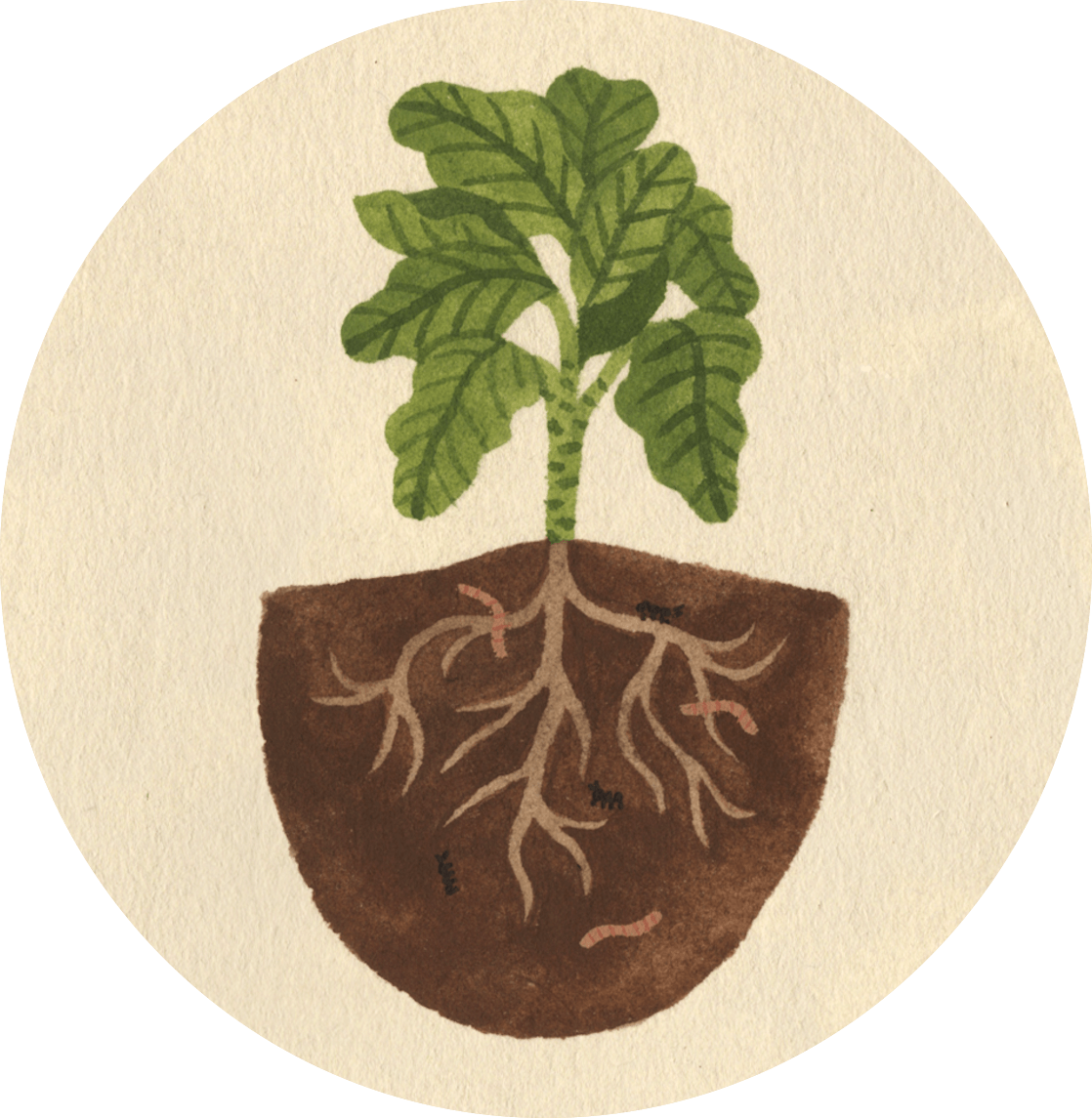

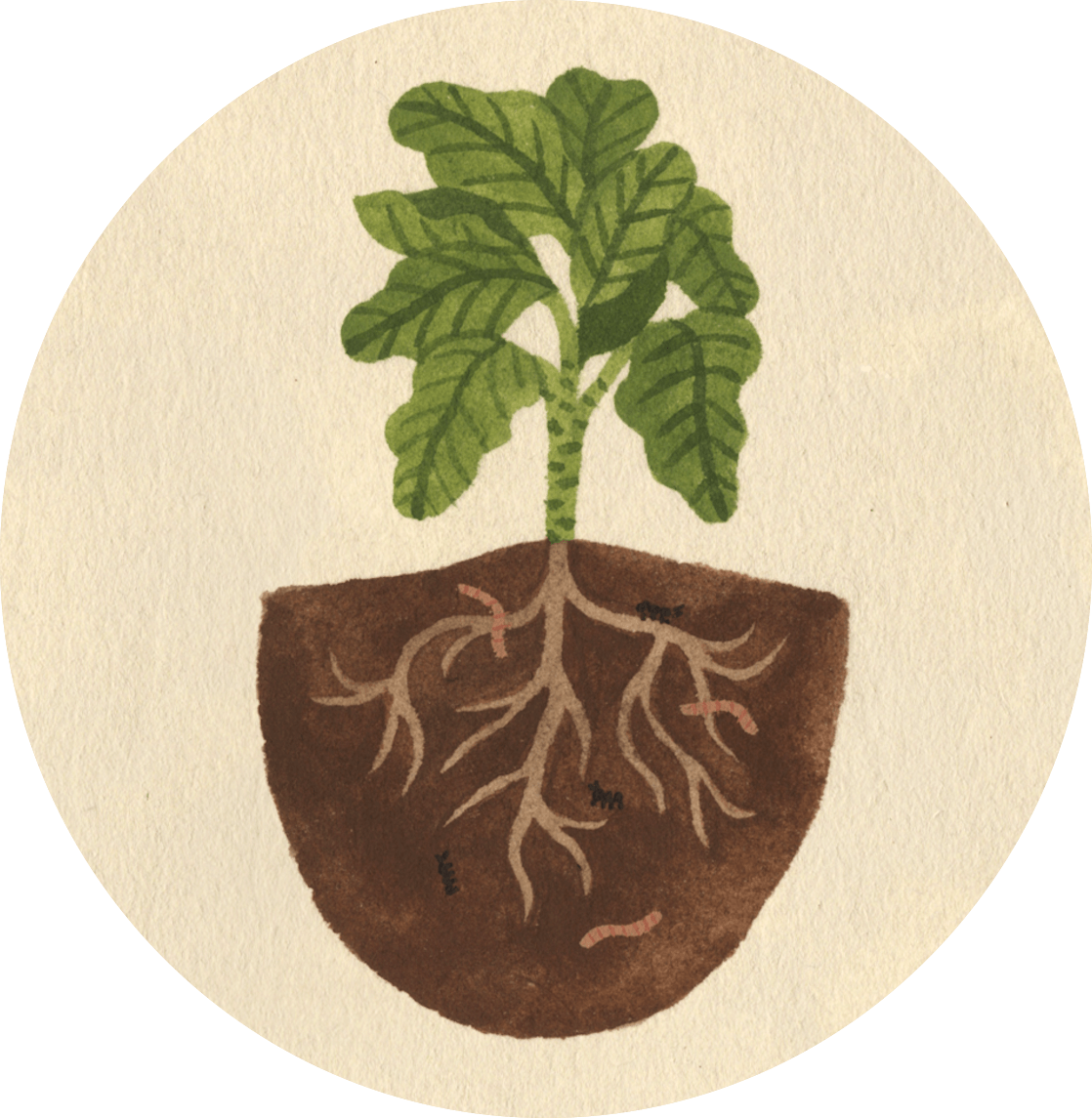

The New York Times has called it the yoga of farming. The phrase “regenerative agriculture” was coined in the 1980s but has its roots in Indigenous and small-scale farming traditions around the world. Instead of tilled rows of monoculture crops on depleted soil, regenerative farms follow a few basic tenets: disturb the earth as little as possible (that means putting down tillers and minimizing synthetic pesticides and fertilizers), never leave the soil bare (farmers plant cover crops like clover and legumes between rows) and embrace biodiversity, both aboveground and below. Proponents say that diverse crops and, optionally, carefully rotated grazing livestock help fuel microscopic soil biodiversity, which, combined synergistically with other regenerative practices, increases soil’s water and carbon absorption power. That makes farmsteads like The New Farm notably more flood- and drought-resistant, and potentially more greenhouse gas–absorbent, too.

Now the concepts are spreading like wildfire. You’ll see the term “regenerative agriculture” cropping up in news feeds, on the back of cereal boxes and in celebrity-studded Netflix docs. Big Food players like General Mills, Danone, Unilever and Nestlé are ramping up regenerative pilots around the globe. Apparel brands like Patagonia, Gucci and Timberland are preaching the powers of regenerative farm-to-closet fashion. This past Earth Day, PepsiCo announced it would be implementing regenerative practices across its entire ecological footprint. The new Pepsi challenge? Convert all seven million acres of its ingredient supply by 2030, starting with 500,000 acres by year’s end. The move, it said, would eliminate three million tons of greenhouse gas emissions by the end of the decade. “Today, we’re accelerating our Positive Agriculture agenda, because we know we have to do even more to create truly systemic change,” said Jim Andrew, PepsiCo’s Chief Sustainability Officer.

Whether you buy the sincerity of their press releases or don’t, there’s no denying climate change is threatening the world’s food supply. Illycaffè’s chair, Andrea Illy, has been vocal about the looming reality that by 2050, “about three-fourths of the land used to grow Arabica coffee will not be suitable.” Similar stats threaten a number of global commodities. Food companies are betting on regenerative practices as a win-win to help them future-proof the food sector: the climate-resilient crops stabilize long-term swings in food supplies while helping companies meet net-zero emissions pledges and keep climate-risk-averse investors happy. And farmers – big and small, organic and conventional – who try regenerative on for size say they’re boosting yields and increasing profits, all while healing the planet.

LEAVE NO SOIL UNTURNED

Until she happened upon France’s Ministry of Agriculture initiative on the role of soil in combatting climate change, Flies had no idea she had unwittingly been wrecking her soil’s natural structure through an age-old practice. It turns out tilling the land destroys complex fungal and microbial networks that make up the earth’s life-sustaining microbiome – all while releasing valuable moisture into the air and quietly unleashing billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere.

Flies ended up doing farmer-led research trials on their tilled versus untilled fields with the Ecological Farmers Association of Ontario. “What we were finding was we could get on untilled fields a month earlier, [our salad greens] would germinate almost a week faster, [untilled fields] would retain more water in the soil, and our yield was higher,” she says. “We couldn’t believe it.”

Tilling is just one of a number of farming methods that have diminished the soil’s capacity to lock in carbon. Rattan Lal, a professor of soil science at Ohio State University, estimates that agricultural practices have released 135 billion tons of carbon into the atmosphere since the start of the Industrial Age – emissions that remain there to this day.

The infamous Dust Bowl of the 1930s transformed the American and Canadian Great Plains into “black blizzards” of eroded topsoil after settlers plowed under millions of acres of native grasslands (grasslands that are now one of the most endangered ecosystems on the planet) to plant water-intensive cash crops. After years of drought and over-plowing, farm dreams turned to dust and accelerated farming’s great carbon release.

While Prairie farmers of the era were eventually encouraged to plant “a great wall of trees” and set up irrigation systems to restore their soil and put an end to the Dust Bowl, destructive farming practices persist. In the last 30 years alone, one-third of the world’s usable land has been severely degraded, according to the United Nations. Another 75 billion tons of fertile topsoil is lost every year.

An Oxford University–led study published in the journal Science last fall noted that “even if fossil fuel emissions were eliminated immediately, emissions from the global food system alone would make it impossible to limit warming to 1.5°C and difficult even to realize the 2°C target.”

As the researchers concluded, “major changes in how food is produced are needed if we want to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement.”

FEDS INVEST IN CLIMATE-SMART FARMING

Federal estimates reckon that Canada’s crop and livestock farms are responsible for 10% to 12% of Canada’s overall carbon footprint. Part of that comes from fossil-fuel-run farm equipment; another chunk comes from methane produced by cows and liquid manure (used on intensive livestock farms); a large portion comes from petrochemical-based inputs, especially nitrogen fertilizer, which releases nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas that’s 300 times more potent than Co2.

The task at hand is to turn those farm fields back into carbon sinks. A coalition of 20,000 conventional and organic farmers asked the feds to invest $300 million in the 2021 budget to help farmers embrace climate-friendly practices, such as planting cover crops, reducing nitrogen fertilizer and rotating grazing. “We calculated that with a 15% uptake of these practices on farms across Canada we could mitigate 10 million tonnes of carbon,” says Flies, one of the co-founders of the Farmers for Climate Solutions (FCS) coalition. “All of us recognize that for farmers’ sakes, we need more profitable and resilient farms, and for the climate’s sake, we need to reduce our emissions and be part of the solution.”

“All of us recognize that for farmers’ sakes, we need more profitable and resilient farms, and for the climate’s sake, we need to reduce our emissions and be part of the solution.”

–Gillian Flies, Farmers for Climate Solutions

In the spring, Marie-Claude Bibeau, Minister of Agriculture and Agri-Food, signalled that the ministry was on board, announcing that Canada would plow $185 million over the next decade into a new Agricultural Climate Solutions program.

In March, the Trudeau government unveiled draft regulations for its Greenhouse Gas Offset System, specifying that “farmers who reduce or remove GHG emissions through regenerative agriculture practices … may be able to generate offset credits which can then be sold, providing a financial incentive.”

It’s all part of Canada’s $350-million investment over 10 years to help the country’s agri-food sector “meet our emission targets and capture new opportunities in the green economy,” including $165 million in the Agricultural Clean Technology Program, $10 million to get farmers off diesel, and $60 million to protect existing trees and wetlands on farms in the latest federal budget. There’s also a proposed national – albeit so-far voluntary – target to reduce synthetic fertilizer use by 30% below 2020 levels.

All these moves should incentivize more farmers to implement regenerative practices, says Gabrielle Bastien, founder of Quebec-based Regeneration Canada: “The federal budget announcement is great news for the regenerative movement.”

Canada isn’t alone. France has taken a leadership role in using soil to combat climate change since hosting COP21 in Paris in 2015. Recently, the Biden administration signalled its support for regenerative agriculture as part of its response to the climate crisis. Across the pond, Prince Charles backed the movement in an op-ed for The Guardian in May, saying, “We must ensure that Britain’s family farmers have the tools and the confidence to meet the rapid transition to regenerative farming systems that our planet demands.

GROWING REGENERATIVE IN THE WILD WEST OF CARBON CREDITS

There’s no hard data on exactly how many regenerative farms exist in Canada or globally, but what’s certain is that there currently aren’t enough of them to meet corporate pledges. Companies like Wrangler, Kering and others are posting global call-outs to farmers, issuing grants to those who want to participate in regenerative pilot programs. PepsiCo says it’s investing US$10 for every acre that farmers convert to regenerative.

The challenge now is getting everyone to agree on what qualifies as regenerative, particularly in the wild west of carbon credits and net-zero pledges. At this point, there’s no universal standard for regenerative agriculture, though food policy guru Wayne Roberts told Corporate Knights before he died earlier this year that’s part of what he appreciated about regenerative agriculture: its “open-endedness, its lack of clear, binding and dogmatic definitions, its openness to what good people can do as they try to accomplish what’s possible.” He added, “It avoids the problem of turning the perfect into the enemy of the very good, which has been the bane of social change movements for a century.”

A wide array of farm movements currently unite under regenerative agriculture’s banner – including tree-hugger favourites like permaculture and moon-cycle-aligned biodynamic farms that are free of chemical inputs, and, increasingly, large conventional farms experimenting with “regen” basics like no-till and cover crops.

More than a third of U.S. cropland is now considered no-till, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics, with a small but growing number of farmers trying their hands at planting cover crops, which keep carbon from escaping from bare soil while pulling atmospheric nitrogen into the earth, where it acts as a natural fertilizer.

Trey Hill, a third-generation corn and soy farmer on Maryland’s Chesapeake Bay, thought it was all a bunch of “environmental BS” but decided to take up the state of Maryland’s offer to pay farmers to plant cover crops on bare fields two decades ago.

“I thought it was greenwashing,” he said during a webinar on soil carbon sequestration, organized by the U.S.-based Business Climate Leaders, in May. Until he saw a dramatic difference between two fields. That spring, his business-as-usual fields were unplantable, while the ones green with cover crops left him stunned – they were ready for planting far earlier. “We realized everything we had been taught … was having to be rethought.”

“We realized everything we had been taught … was having to be rethought.”

–Trey Hill, a third-generation corn and soy farmer

Hill now grows a variety of clover, rye, lentils, radishes and turnips in his cornfields as sequestration and regeneration agents. Fast forward to early 2020, when Hill became the first American farmer to participate in a national carbon credit system set up by a Seattle start-up called Nori. Last year, Hill was paid US$115,000 for practices that had sequestered more than 8,000 tons of carbon in the soil over five years. If he can demonstrate that his 10,000 acres are able to store an additional ton of carbon per acre each year, he could pocket another $150,000 annually. Nori’s not alone. Another agri-tech start-up, Indigo Ag, has stated that it hopes to pay regenerative farmers to capture a trillion tons of carbon dioxide from the air, selling offsets to companies like Maple Leaf Foods.

Questions remain about the efficacy of carbon offsets in the climate fight. Can regenerative farms legitimately sequester trillions of tons of carbon dioxide? Are carbon markets for farmers worth the gold rush – both for farmers and investors? Or will buying farm offsets essentially provide cover for heavy-emitting companies to keep polluting? There’s a great deal of scientific debate – and ongoing research in field labs – around just how much carbon soil can sequester, with a growing number of scientists cautioning that regenerative advocates may be overselling soil’s ability to absorb the world’s carbon pollution and effectively reverse climate change.

Sitting on his old family farm half an hour south of Saskatoon one morning in May, Darrin Qualman, director of climate crisis policy at the National Farmers Union (NFU), emphasizes that regenerative farming is “fantastic” at revitalizing soil health and increasing biodiversity and notes that “if we farm better, including regenerative, we can put most of that carbon that farming has released since we plowed the Prairies back in the soil.” That said, he adds, “some suggest you could use soils to suck all of the CO2 from industry, transport, coal and oil out of the atmosphere in decades, and that’s fanciful at best.” It’s a miscalculation that he calls “a potential civilizational error.

DITCHING THE CHEMICAL TREADMILL

Beyond the carbon debate, internal discussions remain over whether chemical pesticides and synthetic fertilizers should be permitted by regenerative farmers. On his Maryland farm, Hill, like many conventional regenerative farmers, uses chemical herbicides to “terminate cover crops” before planting, but he tells the webinar audience that he’s managed to lower his herbicide rates. One poll found that 92% of no-till farmers planned to use the chemical herbicide glyphosate to keep weeds in check and tamp down cover crops without uprooting them. Which helps explain why agrochemical giants like Bayer (owner of Monsanto) and Syngenta are chatting up the benefits of climate-smart regenerative techniques. Bayer says that while it’s paying U.S. farmers to try no-till and cover crops to sequester carbon, farmers aren’t required to purchase Bayer’s “industry leading crop protection” products to participate in the Bayer Carbon Program. Nonetheless, no-till is undeniably good for business.

“Some suggest you could use soils to suck all of the CO2 from industry, transport, coal and oil out of the atmosphere in decades, and that’s fanciful at best. [It’s] a potential civilizational error.”

–Darrin Qualman, director of climate crisis policy at the National Farmers Union

Regenerative practitioners, however, say that if farmers continue to incorporate a wide variety of regenerative techniques, they should be able to cut back naturally on their chemical inputs. That’s one reason why regenerative agriculture is said to save farmers money. One study published in 2018 looked at 20 corn farmers and found that nearly a third of conventional farmers’ gross income went toward external inputs, compared to 12% in regenerative fields.

The NFU and FCS, as well as the feds and others, seem to agree that the most critical factor is getting farmers to reduce their nitrogen use. “The big piece that’s driving up farm emissions is not farm fuel use or cattle or anything else. It’s nitrogen,” says Qualman, pointing out that the energy needed to create, transport and apply one tonne of natural-gas-derived nitrogen fertilizer is nearly equal to two tonnes of gasoline. Canadian farms have tripled its use since 1980. Qualman’s 2019 climate report for NFU outlines how farmers have been pushed to adopt a maximum-output, maximum-input production model contingent on pumping degraded soils full of increasingly pricy fossil-fuel-derived fertilizers and pesticides. “Two things happen when farmers become overdependent on purchased inputs: emissions go up and net incomes go down.”

Qualman says he’ll gauge just how serious companies are about both their regenerative and climate commitments by whether they’re driving absolute reductions in nitrogen use

IT’S A HONEY OF AN O

In March 2019, General Mills launched its first regenerative agriculture pilot as part of a pioneering pledge to make one million acres (or 20% to 25% of its ingredient sourcing supply) regenerative by decade’s end. It’s now in its third summer of a three-year pilot consisting of 45 conventional and organic oat growers in the Northern Plains of North Dakota, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

“We’re doing baseline soil measurements in those fields, sampling organic matter in the soil, as well as measurements around insect and bird diversity and water infiltration [in addition to] soil measurements for carbon sequestration,” says Tom Rabaey, a senior agronomist overseeing the pilots for General Mills. They’re also working with researchers at the University of Manitoba and Saskatchewan who are measuring the GHG-sequestering potential of cover crops.

Rabaey explains how General Mills had been focused largely on carbon footprint analysis and efficiency gains until it started talking to The Nature Conservancy and the Soil Health Institute about the importance of soil health in building resilience in the face of climate change. “Regenerative agriculture is really the lever to help us meet our GHG goal, but [it’s] also a way for us to maintain our supply chain resiliency where we buy our ingredients,” including oats from the Canadian Prairies that go into products like Cheerios, Nature Valley, Annie’s and Cascadian Farm Organic.

“Times were really tough, and farmers were throwing all their income on more inputs, more fertilizer, more pesticides, more efficiency gains, more output per acre.”

–Tom Rabaey, a senior agronomist, regenerative agriculture pilots, General Mills

“Times were really tough, and farmers were throwing all their income on more inputs, more fertilizer, more pesticides, more efficiency gains, more output per acre. We were hearing that,” Rabaey says.

General Mills isn’t point-blank asking farmers to reduce nitrogen and pesticide use, but Rabaey says many farmers in the pilot are doing so on their own. “Usually after the second, third or fourth year, we’re finding that growers start to make those cuts themselves.”

Whether their approach will get nitrogen use down by 30% in line with proposed federal targets is still up in the air. The official figures will be released after this season of data collecting.

BEYOND ORGANIC

While researchers across the continent refine their soil carbon measurement techniques, a handful of certifications have cropped up offering verifiable standards for regenerative farmers. The Soil Carbon Initiative (SCI) cites Danone and Ben & Jerry’s as partners. On the organic side, Dr. Bronner’s, the Rodale Institute, Nature’s Path Organic and Patagonia helped launch a regenerative organic certification (ROC) last fall. The ROC seal takes organic as a baseline but adds clear standards for a living wage and grazing livestock welfare in addition to a whole host of soil-building requirements.

Among their first products on shelves: certified organic regenerative oatmeal by B.C.-headquartered Nature’s Path. “As demand increases, our plan is to transition more products to ROC certification,” says Samantha Falk, director of communications for the cereal company.

Back in Creemore, Flies is working on making The New Farm the first certified regenerative organic vegetable farm in Canada. After that? “We want to train 10,000 farmers as leaders.”

“My dream is we can support farmers to be a part of the solution to climate change,” Flies says. “We have a huge opportunity here to improve livelihoods of our farmers, improve the quality of our food and sequester carbon all at once, if we do it right.”

COMPANIES COMMITTING TO GOING REGENERATIVE

Patagonia: The green pioneers have been spearheading a certified Regenerative Organic seal with the Regenerative Organic Alliance and using certified ingredients to make cotton T-shirts and the like.

Timberland, Vans and NorthFace (VF Corp. companies): All main materials are to be recycled, regenerative or renewable by 2025. Timberland is currently piloting a regenerative rubber supply.

PepsiCo: The company says all seven million acres of PepsiCo’s farm footprint will be regenerative by 2030, more than 500,000 acres in 2021.

General Mills: In 2019, General Mills announced its goal of having one million acres be regenerative by 2030.

Kering: Gucci’s parent company is funding the transition of one million hectares of land to regenerative practices with Conservation International, as well as one million in protected habitat “outside of its direct supply chain.”

Nestlé: The Swiss giant that purchases 1% of the world’s agricultural output expects to source more than 14 million tons of its ingredients through regenerative agriculture by 2030.

Danone: Its North American regenerative soil health pilot, now in its third year, has 82,000 acres enrolled, with a goal of reaching 100,000 acres by 2022.

Wrangler: The clothing manufacturer is launching a Retro Premium “Regenerative Jean.” It has invited farmers from around the world to submit documented evidence of improved soil health to be considered for inclusion in the special collection.

Cargill: The food giant is supporting farmer-led efforts to adopt regenerative practices on 10 million acres of cropland in North America.

Illycaffè: The Italian company is transitioning its entire network of coffee farmers to “virtuous” regenerative agriculture by 2033, its 100th anniversary.

Adria Vasil is the managing editor of Corporate Knights and the bestselling author of the Ecoholic book series.

From Corporate Knights Summer Issue, in print June 30, 2021.