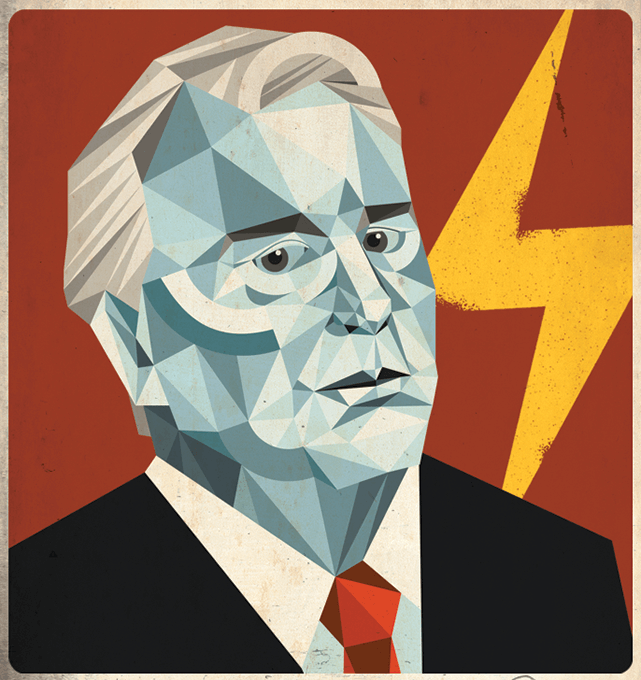

Duke Energy is among the biggest electric power companies in the United States and one of the largest emitters of greenhouse-gas emissions in the world. It serves four million electricity customers, boasts 18,250 employees and controls about $63 billion in assets that together generate $12 billion in annual revenues. The chief executive heading up this company is James Rogers, described by many as “silver-tongued” for his ability to convince many of his industry peers that climate legislation makes sense. Rogers, who oversees about 36,000 megawatts of coal-heavy generating capacity in the Carolinas and Midwest, supports the idea of cap-and-trade legislation. More than that, after years of battling unknowns he wants greater certainty for his industry.

Corporate Knights caught up with Rogers at the biennial GLOBE Conference in Vancouver, British Columbia, in March. Here is an edited excerpt from that wide-ranging discussion, which touched on everything from the importance of collaborating with China to the job-creation benefits of emissions regulation:

CK: You said during your talk that you forecast a dramatic change in U.S. energy sources over the next five years. Can you explain?

ROGERS: I was looking at a macro trend. I believe that the use of coal in the United States is going to decline steadily. We’ve just put $7 billion down to build two advanced coal plants – a super-critical plant and a coal gasification plant. As a consequence of building this new capacity of 2,600 megawatts, we’re going to shut down 3,700 megawatts of old, high-emitting coal plants. There’s going to be about 50,000 to 100,000 megawatts of these (older coal plants) retired over the next 10 years. The use of coal is going to fall, and producers in the U.S. have already got that message and have begun exporting coal to China.

CK: Your comment about the importance of collaboration with China was interesting. Do you get any pushback on that, given that in certain circles of U.S. politics there is a lot of anti-Chinese sentiment?

ROGERS: The differentiation is this: we’re working on infrastructure. If we can do it more affordably by working with the Chinese, all of our customers benefit, whether they are commercial, industrial or residential. For instance, take the Westinghouse AP1000 nuclear plant (being built in China). If they’ve built one or two of these, and we’re collaborating with them on building ours, we’re going to build it cheaper. You know, it’s like the old West Texas expression: the pioneers get the arrows, and the settlers get the land. It’s going to be smart for us. Already there’s a Chinese company that’s focused on the CAP1400, which is the next generation of the AP1000. So that’s one of many examples of where working together works, because if we can improve our infrastructure in this country, make it cleaner, maintain our level of reliability, and make it more affordable than a traditional build-out, then our people benefit.

CK: And the China bashing?

ROGERS: I understand the China bashing, but it’s not a smart way to think about the future. We’re better off in the U.S. to collaborate with the Chinese and work with them. If you go back to 1880, when the U.S. was having its wave of growth, if smart French, British and German companies had invested in the U.S., there would have been great opportunities. In the same way, we need to take advantage of China’s intellectual property of scaling, and their significant greenfield advantage. They can do things so much faster, scale better, and that can easily translate into lower cost.

CK: Clean Air Act amendments that came into force in December targeting mercury and smog-causing emissions have created quite a stir in the industry. What was Duke Energy’s position on these regulations?

ROGERS: Well, we didn’t oppose them. We have this modernization program that is allowing us to shut down 37,000 megawatts, which is going to reduce, rather dramatically, our cost of compliance and our ability to comply. Our industry has known for a decade that new sulfur and nitrogen oxides and mercury regulations were on the way. That’s why we started in 2005, 2006 building new generation to retire these old coal plants.

CK: Some call the regulations job killers. Others call them job creators. What do you think?

ROGERS: It’s a job creator, because if you have to retrofit your units it creates jobs. If you retire plants, and build new plants, it creates jobs. So in an interesting sense, yes, it increases (electricity) rates, but rates are going to go up anyway, and for 50 years the real price of electricity has been flat. So I do think these new regulations create more jobs than they destroy. What it really does is start the process of modernizing our generation fleet, which we’re going to have to modernize by 2050 anyway. This just gets us on that road.

CK: You mentioned rates are going up anyway. Presumably that’s a message customers don’t like to hear.

ROGERS: As the unit price goes up, you try to mitigate the bill. We can help our ratepayers along the way with our conservation efforts. An interesting thing is if you ask the average American what they pay per kilowatt-hour, they don’t have a clue. However, if you ask them what they pay for gasoline, everyone can rattle that off. This, despite the fact that people pay more per month for electricity than they do on gasoline! Again, the regulation was expected, and that is going to accelerate our modernization. If we really invest in energy efficiency we can mitigate the cost impact, and all while creating jobs.

CK: Controversial plans to build out oil and natural gas pipeline infrastructure seem to dominate the headlines these days. Are you surprised that we spend so much time focused on pipelines and so little time focused on transmission lines?

ROGERS: Let’s be real. All the guys in Congress who are telling me they’re for renewables, they won’t vote for eminent domain to build transmission. The provision in the Cheney bill (National Interest Electric Transmission Corridors) is not forceful enough to allow rapid transmission line construction. Gas pipelines basically have eminent domain, so you can just build them. You don’t have to get a corridor, and then go through years of litigation, and so no one has really faced up to it.

CK: Do you have a position on the Keystone XL pipeline controversy?

ROGERS: I’m very supportive of the president, but the (original) decision not to support the Keystone pipeline was a mistake. The network of underground pipelines that we currently have in the United States moves everything from natural gas to refined products to jet fuel. They could have deviated around Nebraska, if that was the big issue, but look at all the pipelines that currently go through Nebraska. I think that it’s a job-killing decision and a mistake for our country.

CK: The obsession remains bringing oil and gas from Canada, but what about electricity? We have $70 billion in oil crossing the border, but only $4 billion in electricity.

ROGERS: If you can do the math, and build the transmission, then that’s a good solution, but you’re not going to be able to build it all the way up to North Carolina. But you could go to New York, and you could go to the Midwest. The bottom line is that until politicians vote for eminent domain, it’s not going to happen.

CK: But are people lobbying hard, in the same way that they are lobbying for the pipeline?

ROGERS: I think they are, but the math doesn’t add up. Look at the cost of renewables, the cost of the transmission, the need to back it up with a gas unit so that you can make the economics of the transmission line work. We need to keep our product affordable. We’ve built 1,800 megawatts of wind and solar, but we have sold it to people who are close to where the wind is blowing. We are looking at building a transmission line that will bring power into California, but we think of that as a 10-year project, and a very difficult one. We’re investing a little bit, while recognizing that it’s going to take a change in the law to allow this to happen in an expeditious and profitable way.

CK: You talk about natural gas as a transition fuel to new low-carbon technologies, but doesn’t its low cost and abundance make it harder to transition to renewables?

ROGERS: The current price makes it very difficult. But I think you still have renewable portfolio standards (RPSs), which require the building of renewables in those areas. So I do not think it (cheap natural gas) slows it down, because of these RPSs. We’ve seen the demand fall in recent years, but we’ve also seen a rebound this year. We’re building 800 megawatts of wind and solar this year, and we didn’t expect to build so much in 2012, but there was this huge rush before the end of 2012 to take advantage of the tax credit.

CK: You also mentioned that you were building more natural gas-fired power plants in response to the shale gas boom?

ROGERS: We had this planned a number of years ago. We’re bringing on 2,630 megawatts of plants. Great heat rates and low gas prices – this is something that I haven’t seen in 24 years as a CEO. We are dispatching our combined-cycle gas plants as a baseload before all our coal plants, right after our nuclear plants. So we’ve changed the hierarchy of dispatch. I find it remarkable.

CK: Is that because it’s cheaper?

ROGERS: It’s cheaper, and it’s more efficient. So when you take the combination of the cheapness of the BTUs, coupled with the 7,000 heat rate, versus 10,000 heat rates in some coal units, you just burn it more efficiently. Plus there’s lower carbon footprint, no sulfur, no soot, etc.

CK: What carbon price do you use when making long-term projections? Rogers: We use a scenario of prices, from $30 to $50. The reality is that if you’re building a plant for 60 years, I operate in a world where there is going to be carbon regulation at some point. I operate in a world that if I can find a way to create zero emissions generation, that’s the tack I should be on. I was active in pushing for U.S. carbon legislation, which will ultimately be necessary going forward. I’ve come to believe that by doing the things we’re doing in China, developing technologies, doing pilots with startup companies, we’re going to do more to achieve that (carbon reduction) objective than most utilities. If you look at the change-out of our basic fleet, some was recession-driven, and now it’s driven by new technology, like burning gas before all our coal units. Our carbon footprint is going to be as low as it would have been under Waxman-Markey by 2020. It’s an interesting confluence, and obviously the recession is not a good factor, but that confluence is putting us on a long-term path to decarbonizing our generation fleet in America.