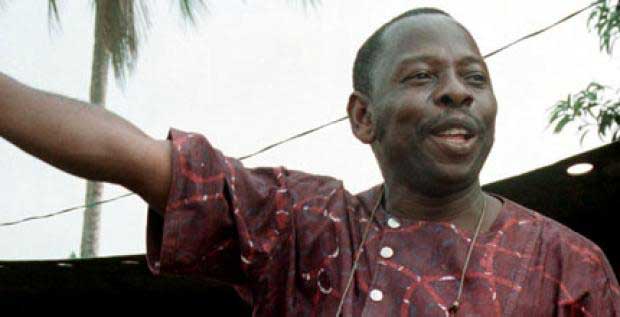

What’s the murder of Ken Saro-Wiwa mean?

In the turbulence of the aftermath of my father’s death one question stood out in my mind. It was in the London Guardian and a Nigerian journalist Chuks Illoegbunam posed and answered his own question: Ken Saro-Wiwa’s death means nothing has changed.

It was as much a challenge as a question, a challenge to his readers, to everyone who had been appalled that a man, a writer, who had prosecuted an environmental cause on a nonviolent platform, could be met with the indifference and hostility of a multinational and then judicially murdered by a kangaroo court in front of a global audience.

It is almost 10 years since my father’s murder and as I reflect on the interim, I am still haunted by the circumstances and consequences of his death and it depresses me that Chuks’s challenge has proved prophetic because nothing has changed—despite the outrage at the circumstances of my father’s death we still live in a world where corporations routinely put profits before people and the planet, a world in which they can, and do, get away with murder.

There are many reasons why my family and others decided to seek judicial redress not the least of which was because we wanted Shell Oil to account for their actions against Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni. In his last statement before his sentencing by a military tribunal my father observed that “Shell is here on trial. The Company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come.”

There are many reasons why my family and others decided to seek judicial redress not the least of which was because we wanted Shell Oil to account for their actions against Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni. In his last statement before his sentencing by a military tribunal my father observed that “Shell is here on trial. The Company has, indeed, ducked this particular trial, but its day will surely come.”

That statement was uppermost in our minds when the Centre for Constitutional Rights advised Ken Saro-Wiwa’s family of the possibility of bringing the multinational to court in the US. We filed a complaint in 1996, accusing Shell of crimes against humanity, torture, summary execution, arbitrary detention, and racketeering claiming that Shell’s actions in Nigeria had violated the Alien Tort Claims Act, the Torture Victim Protection Act, and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act.

It took six years of legal arguments and appeals, chiefly over jurisdiction, before Judge Kimba Wood declared in our favour on February 28 2002 acknowledging that there was sufficient evidence of collusion between Shell and the Nigerian military to qualify as racketeering under the RICO Act.

As I write, the case is still in the discovery stage but our experiences so far have confirmed me in my belief that there is a pressing need for a global forum where corporations can be brought and held to account for their actions. In order to see this you have to stand back and place Ken Saro-Wiwa’s murder in a wider, historical context.

In the late 1980s my father was depressed that he had spent most of his adult life working for a better future for a community that had contributed 900 million barrels of oil to the Nigerian government but had received virtually nothing but a ‘devastated environment’ in return for our natural resources. Despite contributing an estimated $30 billion dollars to the Federal coffers, we had no pipe born water, no electricity, no schools or hospitals worthy of the description, an estimated 70% of Ogoni graduates were unemployed and to compound our misery the foreign oil industry had operated to standards that would have been unacceptable in their own backyard; gas was openly flared 24 hours a day, pipelines laid over farmland without community consultation or even carrying out any kind of environmental, social or cultural impact assessment.

But when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, my father saw it as a moment, a moment when the world was encouraging minority peoples in Eastern Europe to stand up for their rights. If it was good for the former countries of the Soviet Union it was surely good for communities like the Ogoni who were trapped in Federal arrangements that robbed us of our resources?

Moreover it was a time when the environmental awareness was high on the public agenda and the Second Earth Summit in Rio would confirm that we were poised to move towards a kinder, gentler world. Capitalism had overcome socialism and it was the end of history. But ten years after the triumphalism of the West, the riots in Seattle occasioned ‘capitalism in crisis’ headlines. What went wrong?

Well the murder of Ken Saro-Wiwa, coming as it did in between the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Seattle riots, proved that unrestrained Capitalism did not deliver higher standards of living but actually contributed to public disorder and human insecurity. The first Gulf War showed that the New World Order was not new, but was a reactionary world that would go to any lengths to eliminate anything or anyone who threatened the status quo in the supply of energy. My father’s murder merely ratified the old world order.

It is no exaggeration to say that my father’s death gave birth to a new industry—Corporate Social Responsibility. The best I can say about CSR is that while I welcome the efforts to promote best practises and standards, business history tells us that corporations were only tempered by labour agitation followed by regulation. The notion that left to their own devises corporations will act as good corporate citizens is a laudable one but one that belies historical experience or the lack of public faith and trust in those institutions.

Because while CSR was being trumpeted and propped up by an artifice of voluntary codes and offered as a sap to its critics, corporations were showing their true hand, working through GATT negotiations or trying to install the Multilateral Agreement on Investment (MAI) and subsequently through the undemocratic offices of the WTO.

The corporate agenda has a bewildering array of blunt, international instruments, organisations and scholarship to advance and promote its cause. And yet, despite all this the gap between rich and poor is widening, wealth is being concentrated in ever decreasing circles and the feeling persists that people and planet are being shackled by the dictates of a corporate agenda that is self-serving and socially divisive.

The riots in Seattle were a wake up call but the enduring legacy of the global justice movement the real message of the global antiwar protests must be translated and represented in an international instrument that will govern and police corporations, rendering them accountable to all stakeholders. How and what form this instrument will take is the big question and the UN Commission on Human Rights (UNHCR) proposed Norms on Business and Human Rights is a good start. Corporations have, to my mind, forfeited the right to self-regulation and our experience of the last 10 years suggests we need an effective forum that will balance the undoubted benefits that capitalism brings with a commitment to protect people and the planet.

Until then Ken Saro-Wiwa’s story will remain a symbol of our collective failure to promote an acceptable face of capitalism. Because despite all the international resolutions and spotlight on Shell and Nigeria, nothing has materially changed in my community. The Ogoni are still waiting for an objective audit of the environment, moreover my family has been forced to beg for my father’s remains and he is still described as a murderer on Nigeria’s statute books.

Ken Saro-Wiwa and the Ogoni struggle was once described as a morality tale of the late 20th century, that is, it symbolised the zeitgeist of an area when indigenous and minority peoples railroaded out of the way by the juggernaut of international capital and power. We hope that bringing Shell to trial will signal the beginning of the end of that era. I have my doubts but morality tales are supposed to be a salutary lesson. Are we still listening?