The battle over mandatory GM (genetically modified) food labeling in the United States has heated up in recent years, with perceived inaction in Congress leading to movements at the state level to pass their own labeling laws. Ballot initiatives in Oregon, California, Washington and Colorado have all rejected mandatory GMO efforts, albeit by slim margins. Industry-led opposition has spent vast sums of money fighting these initiatives, including $46 million on the 2012 California referendum alone. Despite these setbacks, campaigners are preparing for another big push in several Western states in 2016.

In the Northeast, proponents have had more success. Vermont passed a law that would see the adoption of mandatory labeling of GM food by July 2016, although it is currently being challenged in court. Both Maine and Connecticut will adopt labeling only if a number of regional states jump on board first.

This shift to activism at the state level came about – in part – due to long-standing Congressional reluctance to wade into such a sticky issue.

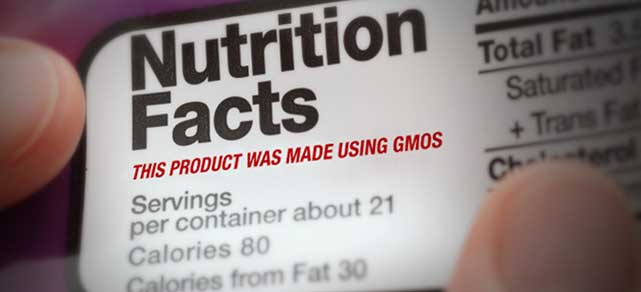

That’s why labeling advocates were caught off-guard when the U.S. House of Representatives passed an under the radar bill titled The Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act by a wide margin last week. The bill would ban any states from passing laws requiring GM food labeling, replacing such efforts instead with a voluntary labeling regime applied nationally.

While it remains to be seen whether the Senate will approve this bill or if President Obama will ultimately sign it, it’s clear that no mandatory GMO labeling is the preferred outcome for big food and biotechnology companies. But is this policy likely to come back to haunt them?

The bill’s sponsor, Kansas Republican Rep. Mike Pompeo, dismissed pro-labeling advocates as “a handful of activists.” Yet nationwide polls have consistently shown overwhelming support for increased transparency. An AP-GfK poll conducted last year found that two-thirds of Americans support labeling of genetically modified ingredients on food packages, while a Mellman Group survey found 89 per cent respondents in favour.

While significant industry expenditures and mobilization have managed to beat back most mandatory labeling laws at the state level, they have not helped efforts to win over a skeptical public to the perceived benefits of GM food. Some pro-GM figures have gone so far as to denounce the industry strategy as entirely counterproductive.

British author, journalist and environmental activist Mark Lynas has converted over the past decade from ardent GM opponent into one of its highest-profile advocates, but he also thinks that industry should hop on board with labeling. He made his case in an interview with Corporate Knights last year.

Effectively spending millions of dollars trying to stop consumers from knowing where their products are being used is essentially the opposite of advertising. That’s tailor-made to make people feel scared about something, if it looks like there is an effort to cover up what the ingredients are in their food.

The way to dispel some of this mythology and fear mongering is to give people access to information. Opponents want a big GM label because they want to stigmatize the product and get it off the shelves. They’re into prohibition, but there’s got to be some kind of middle road where we can actually give people the information that they want without the skull and crossbones stigmatization attached to it. You have to give people the option of finding out what’s in their food. Transparency should be the friend of science on this. If you don’t fill the void, the void will be filled by the conspiracy theorists. Let’s have farmers explain why they’re using GM crops, and scientists demonstrate why they’re continuing to develop them. If you’re Monsanto and you want to explain why it’s beneficial for farmers to use this, you can if it’s labelled. You can’t if it’s hidden.

Risk-communication consultant, author and supporter of GM foods David Ropeik, meanwhile, penned an open letter to big agriculture CEOs in 2013 outlining why labeling is the only way to encourage public acceptance. He made a similar argument to Lynas but approached it instead using language grounded in the cognitive psychology of risk perception.

You don’t need research to tell you that people take risks all the time. Knowingly. What the risk perception research has found is that the ‘knowing’ increases the likelihood they will take the risk in the first place. Engaging in a potentially risky behavior, knowingly and voluntarily, makes the potential risk feel much less scary. This is the underlying psychological reason why the idea of labeling has so much popular support, and is almost certain to become law despite the millions you are spending to forestall the inevitable. We all want choice over the risks we may face. You do too. Choice makes risks feel voluntary. It makes us feel empowered, more in control of our health and safety, and that makes any risk feel less scary. Time and time again, when people are given choice—as labeling would do—their fears are reduced and they engage in risks they fight tooth and nail against when the risk feels imposed.

Many people will be willing to buy products containing GM ingredients if they are openly labeled. And acceptance will grow over time as people become familiar with the label and pretty much forget it’s there (despite the efforts of your opponents, whose opposition will be undercut by your change in position), another aspect of cognitive psychology that supports labeling in the name of increasing acceptance of GM foods.

The Biotechnology Industry Organization trumpeted The Safe and Accurate Food Labeling Act last week as “a viable national solution to the debate around food labeling.” Not all pro-GM voices are so sure.