Apparently, millennials are the most tattooed generation ever. Nearly half of adults aged 18 to 35 have been inked, more women than men have them, and those with tattoos tend to be better educated than those without. There were more than 20,000 tattoo parlours operating in the U.S. last year. Who knew? So what does this have to do with blue chip investing in the green economy? Actually, nothing, except that the incredible growth rates of the tattooed are somewhat similar, albeit unrelated, to the growth in responsible investment (RI).

According to the 2018 Responsible Investment Association (RIA) trends report, more than 50% of Canadian assets under management now integrate at least one type of RI strategy. From 2010 to 2017, RI assets grew by more than 400%. They doubled again in 2019. The RIA is currently collecting data for its 2020 update; expect even further gain¬s. The demographic most interested – also millennials. According to an Environics survey published last year by Mackenzie Investments, they are twice as likely to be interested in RI as baby boomers.

Unfortunately, too little of this RI is getting to climate solutions.

The International Energy Agency reports that investment in the global renewable power sector has experienced small declines each year since 2017. Due to COVID-19, power sector investment is likely to fall by another 20% and efficiency investments over 10% this year. So how does one explain exponential growth in RI yet declining growth in climate solutions investment? Traditional investment products are increasingly being tattooed with labels like “sustainable,” “ESG” and “low carbon.” In our opinion, it’s creating as much confusion as the three-winged eagle inked onto the shoulder of (insert actor’s name here). It’s diverting “willing” capital away from the climate solutions we so desperately need.

Greenchip and other organizations have estimated that global investment of around $2.5 trillion is needed each year through 2040 to limit warming to 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Energy transition investments in 2019 were about $940 billion – we have an annual investment gap of at least $1.5 trillion. And each year that we fall short, the gap just gets bigger. It means that a very uncertain future becomes even more certain.

The problem starts with the taxonomy of “ESG.” The term is often used to capture the entire spectrum of responsible investments, but this is misleading. ESG is instead only one RI strategy of many. ESG is by definition a set of (unstandardized) standards that help score the environmental, social and governance behaviour of individual companies. In practice, ESG integration is a tool that can help identify and manage corporate behavioural risks.

Because of the “E” in ESG, it often leaves investors believing ESG strategies will be overweight in companies selling environmental solutions. This couldn’t be further from the truth.

A quick look at the top holdings of most so-called ESG funds will identify well-known banks, pharma companies and consumer technology stocks – businesses that have little to do with climate change, most of which are already spinning cash and don’t need capital investment. Recently, Greenchip studied the full holdings of the largest global ESG funds. We found that only 5 to 15% of their revenues might be attributed to climate solutions sales, but the higher end of this range is probably a stretch.

Most concerning is that ESG strategies are getting the vast majority of RI investment. According to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance, almost $18 trillion had been allocated globally to ESG strategies by 2018 versus only $1 trillion to thematic “solutions” investments – 18 to 1! The biennial survey will be updated later this year, and the chasm will surely have widened even further.

Another label we find problematic is “low carbon.” These strategies rarely capture the emissions buried in supply chains (known as Scope 2), or worse, downstream emissions (known as Scope 3). It means the emissions from an oil producer might be captured for their extraction and refining, but carbon accounting generally fails to account for the emissions when their refined fuel is combusted.

A recent Economist essay offered an excellent example of how low-carbon accounting can steer investors in the wrong direction with this: “Apple has only a tiny fraction of Samsung’s operational emissions; but Samsung makes things, while Apple has others do that for it.” Accounting myopic focus on operating (Scope 1) emissions can distort investment decisions.

For Greenchip, the main problem with low-carbon strategies is that they also divert capital away from the very solutions they hope to address.

Envision building a large wind farm with all those blades and towers, transmission lines or a new subway system. Manufacturing this equipment and erecting this infrastructure is a pretty carbon-intensive exercise. We often say, “You need to get a little dirty today to build the cleaner economy of the future.” Low-carbon investing (and often the E in ESG) focuses only on the initial pollution that building this infrastructure creates and not on long-term emissions reductions. In our experience, when an investment committee says they want to see a carbon audit of our portfolio, we probably are going to lose that mandate.

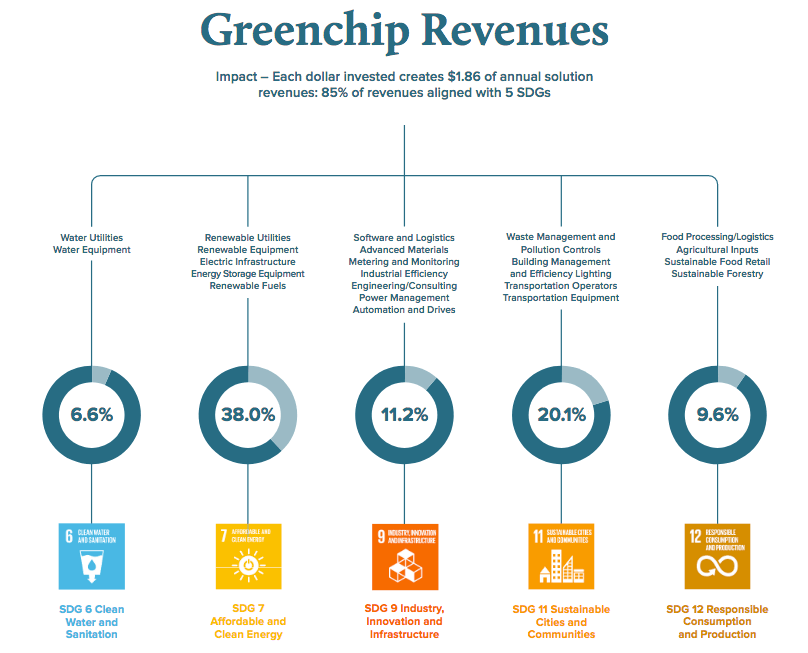

We think there is a more effective way to measure impact than ESG scores or carbon audits: solutions revenues. Every six months, Greenchip attributes all the revenues in our portfolio holdings to specific environmental solutions. As of June 30, 2020, every dollar invested in our fund produced $1.86 in the past year of environmental solutions sales. So, of the $200 million that we oversee, about $370 million is helping to close that $1.5 trillion gap. Our focus on revenue measurement also enables us to attribute portfolio revenues to five United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Simply reallocating even a small portion of the least effective ESG and low-carbon strategies to those focused on thematic “solutions” would go a long way to closing the climate investment gap.

Greenchip still sees value in ESG integration, measuring carbon, engagement, proxy voting and so on. We use all of these tools. They help us mitigate risk and are part of our diligence process. Around the edges, we know better corporate behaviour matters. That said, too often the investment industry is using these labels to “greenwash” traditional allocations of capital. Otherwise, how can one explain the paradox of exploding RI fund flows with declining rates of environmental solutions investment?

John Cook is the president and CEO of Greenchip Financial Corp.