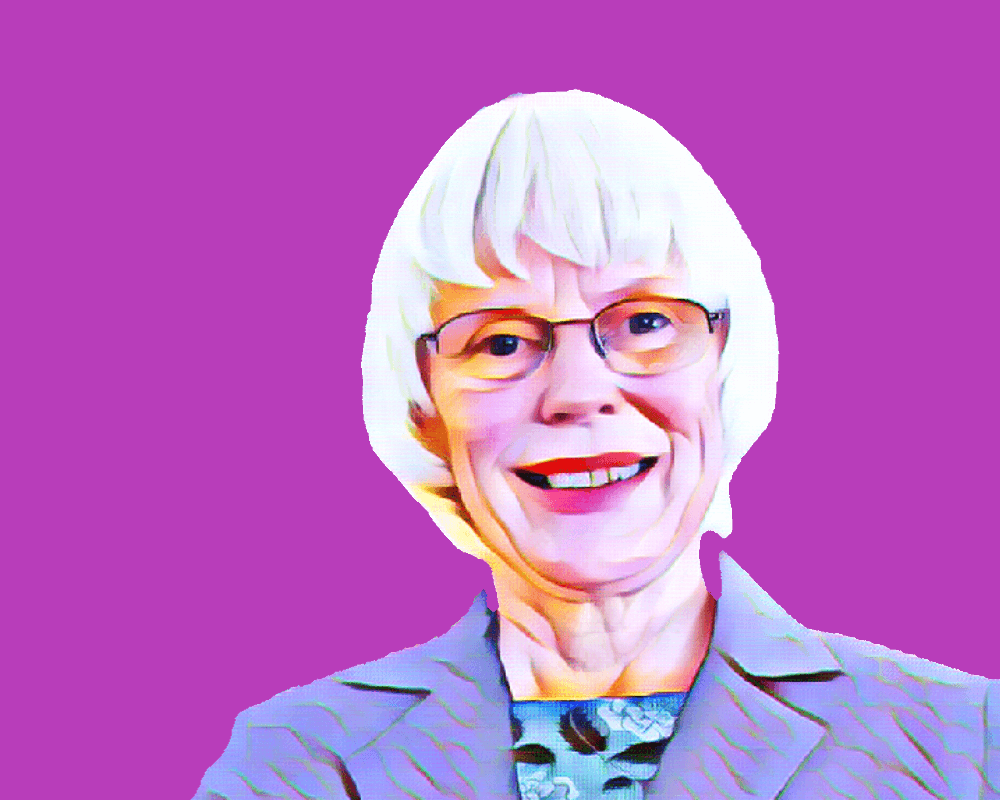

I first met Moira Hutchinson in 1987 when I was working on the first of my series of books on responsible investment. She was generous with her time and provided a wealth of insight into “ethical investing,” as responsible investing was known then.

In that crucial decade of the 1980s, Hutchinson pioneered the practice of shareholder engagement on social and environmental issues, a lifetime achievement for which she was recently appointed a Member of the Order of Canada.

She was named to the Order “for her substantial contributions to Canadian socially responsible investment, notably through the Taskforce on the Churches and Corporate Responsibility.” And her appointment is the first time someone has been appointed to the Order for their work in responsible investment.

During the 1980s, Hutchinson served as coordinator of the Taskforce on the Churches and Corporate Responsibility (TCCR), an ecumenical coalition that operated between 1975 and the late 1990s. Under Hutchinson’s direction, TCCR was instrumental in introducing the concept of shareholder advocacy to Canada, a fundamental strategy of responsible investment. TCCR’s work helped to pressure Canadian companies to disinvest from South Africa and to support sanctions against the apartheid regime in the 1980s.

The task force also worked on a wide range of what we now call environmental, social and governance issues two decades before the ESG acronym became common in the investment world.

“Church investors dared to come to annual meetings to ask questions, or even worse, church investors filed shareholder proposals,” she wrote in a 2018 blog about her early work. “That was very new in Canada. So, company spokespersons and shareholders who were friendly often said, ‘Why don’t you just sell your shares if you don’t like what we’re doing?’ That’s what they really wanted, because then we would be gone.”

In addition to her work with TCCR, Hutchinson has served on the boards of numerous NGOs and on the investment committees of the United Church of Canada and the Atkinson Foundation.

Her influence was felt throughout the responsible investment community. Her fierce advocacy for shareholder rights, for example, inspired much of the early public policy work of the Social Investment Organization, which I led during the early 2000s.

After her appointment, I caught up with her by email to talk about TCCR’s early history and what its work means for responsible investing today.

The following interview has been edited for brevity.

Eugene Ellmen: It’s great that your work with TCCR has been recognized as an important contribution to social and economic justice in Canada. Congratulations!

Moira Hutchinson: Thank you! I’m still in a state of disbelief.

EE: What were the biggest challenges you faced as head of TCCR decades ago?

MH: We operated under the assumption of relatively open access to the shareholder proposal mechanism until 1987, when a court [ruled] that a corporation could exclude a proposal that it believed was submitted “primarily for the purpose of promoting general economic, political, racial, religious, social or similar causes.” The precedent made it easy for corporations to exclude almost any proposal from their proxy circulars until 2001, when this clause was eliminated as part of a broader set of Canada Business Corporations Act (CBCA) reforms.

It wasn’t, however, the legal framework that was the biggest challenge. The legal framework simply reflected the ideas prevalent in the investment community about the meaning of fiduciary responsibility. The consensus was that [investment fund] trustees must act in the best interest of their funds, and “best interest” was primarily defined in economic terms.

Despite the lack of easy access to the shareholder mechanism to influence corporations, TCCR thrived until financial cutbacks in the churches led to its closure in the mid-1990s. We had developed a strong methodology of research and engagement with companies, regulators and governments for work on a range of issues. For example, we developed a significant investor presence on issues of forest land management.

Fortunately, there was continuity in applying what we had learned in this process, as Peter Chapman, the lead TCCR staff in this work, went on to become the founding CEO in 2000 of SHARE (Shareholder Association for Research and Education).

EE: How much of a change has happened in the management/investor relationship in the last 50 years? Have we really emerged from the age of Milton Friedman, when he said in 1970, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business – to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game.”

MH: The “rules of the game” concerning the relationships between corporate managers, institutional investors and society are evolving, and are being reinforced in part through government intervention. It will take vigilance to maintain this evolution. I’m encouraged by the fact that SHARE now brings together more than 120 investors – foundations, asset managers, Indigenous trusts, universities and religious organizations, representing $90 billion in assets under management. Its size and multi-sector representation means it is much stronger than TCCR ever was. Also, like TCCR, it engages with governments as well as corporations on “the rules of the game.”

EE: There’s a general concern about greenwashing and the dissonance between what many companies say they believe about ESG issues and what they are actually doing. Do you feel corporate greenwashing has increased or decreased from the 1970s and ’80s? And what can investors do about it?

MH: Concern about greenwashing isn’t new, although I don’t remember calling it that in the 1980s. Over time, TCCR and other NGOs pressed for maximizing the access of shareholders and other stakeholders to information, shifting the emphasis from corporate responsibility to social accountability. In response, codes of conduct were developed in a number of contexts: mining, forestry, the apparel industry, et cetera. They represented an improvement over when corporate responsibility was measured only in the limited terms of charitable contributions or a corporation’s own definitions of “best practice.”

The role of investors in improving access to verifiable information is also critical. The effort that church investors through TCCR made in the ’80s and ’90s to get improved corporate disclosure continues. I know, from experience on institutional investment committees, how difficult it is to assess asset managers’ claims that they are doing the research and have the commitment needed to truly integrate ESG into their services. I’m encouraged that SHARE, for example, is working on two fronts to address this problem: seeking improved disclosure regulation and bringing together coalitions of investors to meet jointly with asset managers.

EE: The debate about divestment versus engagement in fossil fuels is probably more heated now than ever. What are your thoughts on that?

MH: Choosing among responsible investment tools – positive and negative screening, divestment and engagement – is complicated. They are all important, and the most effective tool will vary depending on factors such as whether the issue is company-specific or broader, timing, the size and type of investor, possibilities for working in coalitions, et cetera.

I’m strongly influenced by my experience with TCCR’s efforts to support the end of apartheid in South Africa. At that time, most anti-apartheid activists outside of the churches gave their attention to divestment strategies. The “clean hands” approach of divestment best expressed the moral outrage of activists over apartheid. As well, divestment was the “hassle-free” alternative for institutions such as universities under pressure from their students and faculties. What was not well understood was the distinction between divestment (selling one’s shares) and seeking disinvestment by companies from South Africa.

The churches, through TCCR, enabled sustained attention to what companies were doing – seeking meetings with management, asking questions at company annual meetings, or even worse, from their point of view, filing formal shareholder proposals for inclusion in the proxy mailing to all shareholders. Early in our history, we were so unwelcome that on one occasion a bank chairman turned off the microphone at the bank’s annual meeting so that a church representative couldn’t ask a question.

How does this history relate to our climate change crisis and the debate over fossil fuels? Both divestment and shareholder action have a role. Climate change cannot be addressed by only changing your portfolio. It must be addressed by changing the economy. So whether or not an investor chooses to own shares in fossil fuel producers, every company in the portfolio – railroads, banks, grocery stores, manufacturers – should be developing a strategy that is consistent with the goal of keeping climate change under 1.5°C. It’s encouraging to see the development of investor coalitions such as the University Network for Investor Engagement, through which university endowments and pension plans are collaborating to press companies on this agenda.

EE: How permanent are the gains of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s in establishing the importance of ESG issues? Will ESG be resilient enough to withstand attacks from the courts (such as the recent decision from the Supreme Court of the United States on climate regulation), conservative business people and politicians, or the culture itself?

MH: There is increasing recognition by investors that addressing public policy is an integral part of responsible investment, and that’s a positive development. Governments create the rules within which markets operate. I can only hope that investor coalitions will continue to press governments on issues related to responsible investment.

Eugene Ellmen was executive director of the Social Investment Organization (precursor to the Responsible Investment Association) between 1999 and 2012. He now writes on sustainable business and finance.