Coal mines are in trouble. Investors continue to flee the sector, while once-giant companies like Murray Energy are declaring bankruptcy. With the coal mining sector on the ropes, now is a great time to pit two of the largest companies — Glencore and BHP Group — against each other to see who is leading the transition away from coal.

Swiss-based Glencore plc (GLNCY) is a diversified company with three main segments: metals and minerals, energy and agriculture. The energy division owns mines in Australia, South Africa and Columbia that produced a combined 129.4 million tonnes of coal in 2018, including 118 million tonnes of thermal coal that was burned to generate electricity. The remainder is metallurgical coal that is mostly used to make steel, which makes it more difficult to replace – at least until new steel-making methods are mainstreamed. Overall, coal accounts for roughly 27% of Glencore’s overall profits.

Glencore, like all coal mining companies, is under pressure from investor groups like the Climate Action 100+ signatories to align itself with the low-carbon economy. The company released a statement early this year that showcased its support for the Paris Agreement and promised disclosure to ensure that “investments are aligned with the Paris Goals.” The company promised to limit coal production to 150 million tonnes per year, which is higher than current production levels, and to set a target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions intensity by 5% by 2020 compared to a 2017 baseline. Glencore has promised to release longer-term targets next year. Unfortunately, actions speak louder than press releases.

Glencore is moving ahead with its controversial United Wambo Coal Project in Australia, although the local Independent Planning Council (IPC) has stipulated that any coal exported from the mine can only go to countries who have ratified the Paris Agreement. Glencore expects this mine to produce about 10 million tonnes of coal per year, which would keep the company below the self-imposed cap of 150 tonnes per year. A company spokesman told The Guardian that “as older mines in our portfolio come to the end of their economic life, all coal projects will be considered.” It’s hard to square these expansion plans with the promise to align investments with the Paris goals, so I’m going to have to rake Glencore over the coals for greenwashing.

Australia-based BHP Group (BHP), formally known as BHP Billiton, is the world’s largest mining company and owns coal mines in Australia and Colombia in addition to other sites that extract iron, copper, nickel and petroleum. BHP produced 72 million tons of coal in 2018, including 29 million tons of thermal coal. Thermal and steel-making coal account for 17% of BHP’s earnings.

Andrew Mackenzie, BHP’s CEO, hinted that the company might divest from coal during an earnings call in August. This followed reports in July that said BHP would be cutting thermal coal production next year. I wouldn’t normally give much stock to this sort of announcement, but I’m smitten by a speech that Mr. Mackenzie gave in London earlier this year about BHP’s response to global warming. “The evidence is abundant: global warming is indisputable,” he said. “The planet will survive. Many species may not.” These are striking words from a coal mining CEO.

BHP announced a short-term target to keep 2022 emissions at 2017 levels, and an ambitious long-term target of net zero operations by mid-century. The company has promised to release medium-term science-based targets next year. I like it when companies put money towards these targets, so I’m happy to see that BHP allocated USD $400 million to their Climate Investment Program with the goal of reducing emissions. A tangible example of this program is a project to replace gas with renewables at their Escondida copper mine in Chile. It’s too early to say how much of a leadership position BHP will earn as the mining industry grapples with climate risk, but I’m cautiously optimistic that they will live up to their promises and avoid the greenwashing trap that so many companies have fallen into. Time will tell whether or not my optimism is warranted.

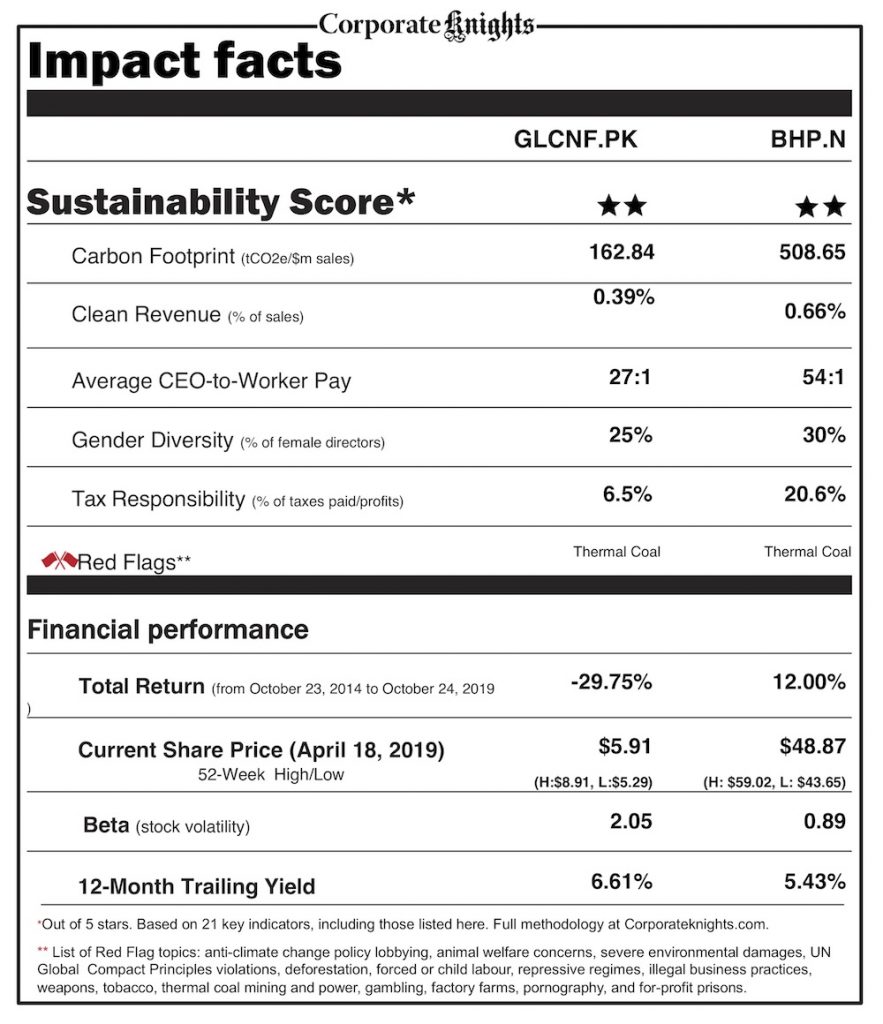

Both BHP and Glencore extract minerals like nickel and copper that are used in clean energy technologies, so there is some potential upside to owning these mining companies as society transitions to a low-carbon economy. However, both companies have significant exposure to carbon risk (as the Guardian pointed out this week). That risk will keep most sustainable investors away. I’ll give this week’s challenge to BHP by a tiny margin since coal – particularly thermal coal – is a lower percentage of their profits. I’m hopeful that BHP will completely divest from their coal holdings and extend its lead, but I’ve been burned too often to take its announcements at face value.

Beta is a measure of a stock’s volatility in relation to the market. By definition, the market has a beta of 1.0, and individual stocks are ranked according to how much they deviate from the market. A stock that swings more than the market over time has a beta above 1.0. Lower beta means less risk.

Have a company in your portfolio that you want to replace with a more sustainable option? Write Tim an email.

Tim Nash blogs as The Sustainable Economist and is the founder of Good Investing.