Ellen Richardson leapt from a bridge in 2001 with the intention of ending her life, only to find herself alive and paralyzed from the waist down. In the decade that followed, Richardson struggled with mental health issues and in 2012, while suffering from clinical depression, was rushed to hospital by ambulance after a call to 911.

Fast forward to November 29, 2013. Richardson wanted to take a plane from Toronto to New York City where she was to catch a cruise ship. But U.S. customs refused her entry because of her 2012 hospitalization. Just how did U.S. customs know about Richardson’s very private health matter?

Ann Cavoukian, Ontario’s dogged information and privacy commissioner, spared little time finding out the answer. In an April report documenting her investigation, Cavoukian slammed Toronto police for unnecessarily feeding 911 information about attempted suicides into an RCMP-managed database – a system she discovered was shared with U.S. border officials.

It’s a serious violation of personal privacy potentially affecting thousands of Canadians suspected of attempted suicide each year, even if those “attempts” turned out to be accidental overdoses.

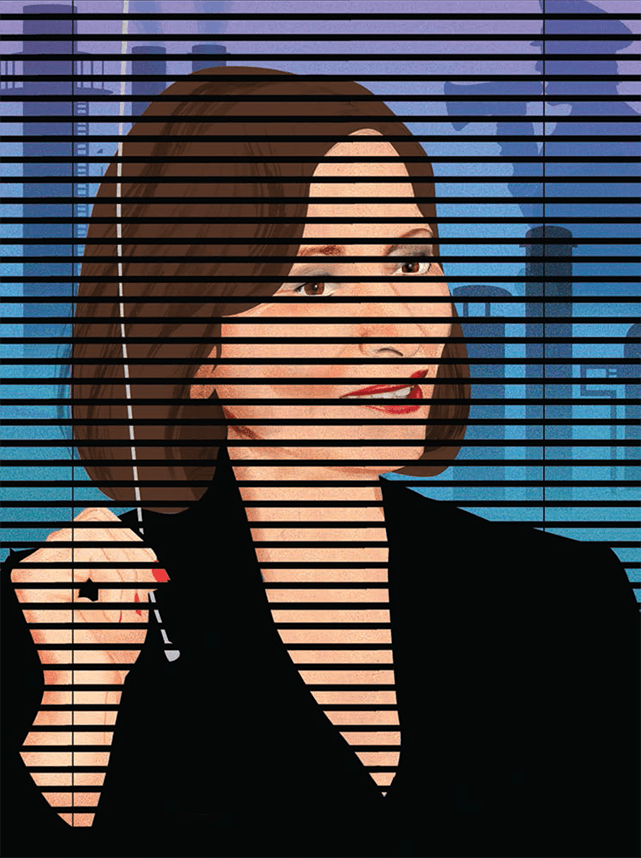

Just a day after releasing her report, Cavoukian is clearly fired up after back-to-back radio and television interviews. Toronto police failed to use proper discretion when it shared the information, she tells Corporate Knights, and now they’re getting defensive. A war of words has ensued through the media. “I wasn’t expecting this to be a scrap,” she tells me.

Vivacious force

If they want a scrap, they’ll get one.

Cavoukian, who has spent three terms and 15 years as commissioner, isn’t known for backing down when the fight is in the public interest, whether that means protecting the personal privacy of citizens or assuring access to information that’s crucial to holding governments accountable.

It’s why Corporate Knights selected Cavoukian for its 2014 Award of Distinction, an honour bestowed in previous years on former prime minister Paul Martin and former Newfoundland and Labrador premier Danny Williams, among others. The award recognizes leaders in Canadian society who have had a “catalytic impact” on advancing a more positive relationship between business, government and sustainable development.

The timing is fitting. Cavoukian leaves her post as commissioner in late June and immediately begins a new chapter in her career as executive director of the new Institute for Privacy and Big Data at Toronto’s Ryerson University. The institute will focus on tapping the power of information to make the world a better place in a way that doesn’t sacrifice personal privacy protections – a crucial caveat in a post-Snowden world.

“We want to show you can do both,” says Cavoukian, who at 60 exudes more energy and enthusiasm than a woman half her age. Toronto Star columnist Jim Coyle once described her as a “vivacious force of nature.”

I ask her about her proudest moments during her years as commissioner. Without hesitation, she cites her battle over an Ontario law allowing retroactive disclosure of adoption records.

The statute, which went into effect in 2007, made it possible for adopted children to seek out their real birth parents, despite past assurances of privacy. “When the adoption disclosure act came out I got so many heartfelt letters from people who were affected by this,” Cavoukian recalls. “I said to the government, look, the promises you made to people in the past must be upheld. We fought it and we won.”

The Ontario Superior Court struck down sections of the law, a decision the ruling Liberal government decided not to appeal. Then-premier Dalton McGuinty “took the high road,” Cavoukian says. “He called me and said look, we were wrong about this, can we work with you to change the statute?” In the end, birth parents were given a veto over any disclosure requests, a balance Cavoukian considered fair.

George Smitherman, Ontario’s minister of health and deputy premier at the time, recalls Cavoukian as “tough and principled but never uncompromising.”

But Cavoukian is more than just Ontario’s privacy czar. Her job has also been to defend public access to information that holds government accountable. On this front, she cites the province’s notorious “gas plant scandal” – a politically motivated decision to cancel two natural gas-fired power plants at a cost of more than $1 billion.

Defender of access

Urged by New Democrat MPP Peter Tabuns to investigate the apparent destruction of relevant electronic documents, Cavoukian determined that key e-mails had been deleted to avoid transparency and accountability. To make matters worse, she learned later of deleted e-mails that weren’t supposed to exist, at least according to senior government staffers she had interviewed as part of her investigation.

“They were lying through their teeth,” Cavoukian recalls. “I’ve never had that kind of falsehood revealed in an investigation.” She says it broke the public’s trust, so much so that in investigations that followed she began demanding sworn affidavits for the first time as commissioner.

“She is clear headed and fearless in pursuit of the public interest,” says Tabuns. Her report on the gas plant scandal, he points out, “shattered complacency about protection of government records.”

Cavoukian was born to ethnic Armenian parents in Cairo, Egypt. At 6 she immigrated to Toronto with her brothers Onnig, the famous Canadian portrait photographer, and Raffi, the popular children’s entertainer.

Armed with a doctorate of psychology (criminology and law) from the University of Toronto, Cavoukian’s first major position in the public service was in the early 1980s as head of research services with the Ministry of the Attorney General. She made her way into the information and privacy commissioner’s office in the late ‘80s, eventually reaching the top job of commissioner in 1997.

She flourished in the role, managing at the same time to co-author two popular books on privacy. (Disclosure: I co-wrote with Cavoukian the 2002 consumer privacy book Privacy Payoff.)

By design

It would be a mistake to think Cavoukian was only concerned with the actions of Big Brother government, or that her voice is confined to Ontario.

The private sector, while under federal jurisdiction in Canada, is where she gained prominence internationally. In many respects, Cavoukian is a rock star of privacy in the corporate context, travelling the world giving speeches to business schools, industry organizations, and large companies – Google and Microsoft among them – about the virtues of building privacy protection into every business decision.

“I always tell people not to think of privacy as just a compliance issue, but to think of it as a business issue,” she explains.

One of her biggest achievements in that regard is her concept of “Privacy by Design,” which embodies seven foundational principles that can help companies proactively build customer trust and loyalty. Engineers are now creating products and chief executives running businesses based on these principles, a reflection of her business-friendly and collaborative approach.

The idea is simple: Businesses need to build privacy into the foundation of everything they do, touch and build. It can’t be added later as a Band-Aid after a breach or violation has already occurred.

Privacy by Design was passed as an international standard in 2010 and the principles have been translated into 36 languages. They form the basis of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission’s privacy programs and will be embedded in European Union legislation later this year.

Cavoukian says public interest in privacy got a major boost last year after American whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed how the U.S. National Security Agency had engaged in sweeping Internet and phone surveillance with no oversight. She has since been bombarded with speaking requests.

“We owe a huge debt of gratitude to Mr. Snowden,” says Cavoukian, adding that it sparked widespread and much-needed debate in the United States – but not so much in Canada. “I think it’s worse here,” she adds, referring to Canada’s highly secretive Communications Security Establishment, a kind of mini-NSA. “What the heck are we doing here about its activities? Hardly anything.”

Internet and privacy lawyer Michael Geist credits Cavoukian for remaining outspoken on this and other issues.

“I think few privacy commissioners have succeeded in placing privacy in the public eye as effectively as Ann,” Geist says. “She consistently identified cutting edge issues such as lawful access or global surveillance and recognized the need for public education and debate. In doing so, her office achieved prominence far beyond what is typical for a provincial privacy commissioner.”