This article was originally published on The Conversation.

As geographer David Lowenthal writes, “Landscapes are formed by landscape tastes.” The lawn – ideally green and lush – is a fundamental component of American landscape taste.

That’s becoming an increasingly expensive taste. Drought-stricken regions such as California are trying to restrict water use by residents, and that puts a target on the lawn. But Americans are wedded to the green, even if some resort to artificial lawns and other water-saving alternatives.

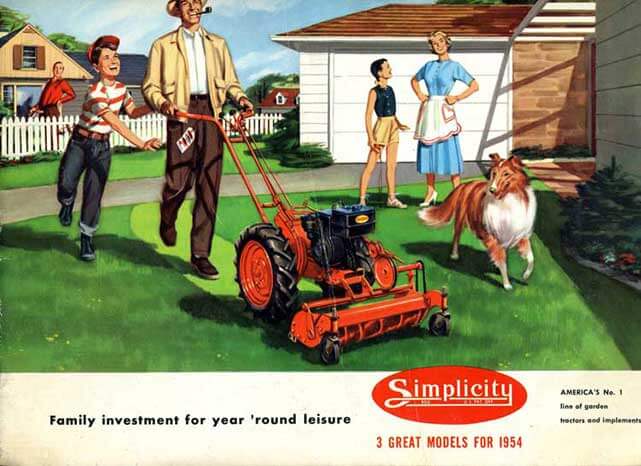

Prying the lawnmower out of the hands of suburbanites will not be an easy task.

The lawn, front yard and back, is a national product, available on shelves, advertised in brochures and modeled on streets everywhere.

The lawns that bind us together

In a country of the United States’ scale and diversity, we have constructed landscapes to bind us together, mechanisms to create a cohesion of comfort despite our dispersed geography. The ways are many, from shared goods to television shows. In this drama, landscape forms a ground of experience that provides identity, structure and meaning.

The lawn is the American garden, and grass is the nation’s largest crop. At the block level, front yards create continuous greenswards. The individual increments of lawn coalesce and their effects multiply. Like actions in our homes or automobiles, any individual change in this domain has only modest impact. But collectively, multiplied by millions, the effects are enormous.

Much of American landscape taste is part of an Anglo-American tradition. The aristocratic residents of English and later American estates idealized the vision of great swaths of grass, maintained by sheep and scythe.

In the 13th century, Albert Magnus wrote, ”Nothing refreshes the sight so pleasantly as fresh mown grass.” The invention of the lawnmower by Edwin Budding in 1830 democratized that ideal for the middle class, and the lawn became a key component of suburban domesticity.

The promotion of a lawn aesthetic

In 1897, a US Department of Agriculture (USDA) agronomist wrote that “nothing is more beautiful than a well kept lawn.” But the taste has deep roots. Lawns are stylized meadows with an association to pastoral traditions, images and ideals. In the 20th century, a lawn aesthetic was promulgated through publications and government agencies and fostered by a lawn industry. They promoted the aesthetic of the perfect lawn: a monoculture of grass kept green year-round, lush, soft to the step, uniformly mowed and weed-free.

The ideal begins to sound venomous when we are confronted with facts such as: grass clippings account for three-quarters of all yard waste and are the second largest source of solid waste in the nation, according to the authors of Redesigning the American Lawn. Change seems improbable with the realization that turf grass is a US$25 billion industry, lawn care over $6 billion and hundreds of thousand of livelihoods are dependent on landscape care and maintenance.

The ideal begins to sound venomous when we are confronted with facts such as: grass clippings account for three-quarters of all yard waste and are the second largest source of solid waste in the nation, according to the authors of Redesigning the American Lawn. Change seems improbable with the realization that turf grass is a US$25 billion industry, lawn care over $6 billion and hundreds of thousand of livelihoods are dependent on landscape care and maintenance.

Surely we are victims (typically willing), but popular taste is powerful and not easily changed. Lawns satisfy deep desires and are a commonplace pleasure, but they are an ecological disaster, and a green lawn in places of drought is a perverse waste of a precious resource, water.

American have been called lawnoholics, but it is moderation, not abstinence, that is called for. There are alternatives.

The impervious surface of the artificial lawn, Astroturf, created not from soil and seed but petrochemicals, is not one of those alternatives. Ultimately, it necessitates a change in our landscape tastes. A new aesthetic along with a new ecological awareness arises in concert.

The shift to a new front-yard aesthetic

Nationally, front yards and sidewalk planting strips have given way to vegetable and ornamental gardens. Wetlands are now preserved instead of drained, and native plants often favored over exotic introductions.

The natural cycle of grass, a perennial, turning brown in the summer can join natural foods and organics as desirable, and at no cost! In dry areas, xeriscape planting, which focuses on plantings that require little water, is an alternative.

In Tucson, the idealization of a green grass lawn gradually gave way to an aesthetic of desert planting, and a new landscape taste emerged. In 1991, Tucson passed an ordinance codifying xeriscape planting and permitting only small “oases” of turf and plants in need of irrigation.

Yale researchers have offered a “Freedom Lawn” as an alternative. They do not propose abandoning the lawn, only limiting its dimensions, altering its constituent elements and modifying its maintenance. The Freedom Lawn has a diversity of plants, eschews the chemical fix and is selectively mown (preferably by hand). It respects lawn conventions. It is traditional and innovative.

In many ways, the Freedom Lawn is a return to medieval practice, the pleasance of the Unicorn Tapestries, with its rich variety of organic life and deep association. The name is catchy and clever, having a patriotic ring and an open-ended set of allusions. The Freedom Lawn implies a liberation from labor and community restraint, conjuring up a return to individualism and away from provincial conformity.

If the small fragments, the pieces that create the mosaic we call landscape, are altered, the total picture will be different.

![]()