Policy-making is increasingly focused on the “appearance” of progress, wherein maintaining appearances becomes an excuse for side-stepping many of the difficult policy choices that must be made. Addressing climate risk has become a critical example of kicking the can down the road – there still seems to be a view that climate risk can be “managed” with aspirational statements and standards.

Consider the behaviour of some of the world’s largest asset managers in response to shareholder resolutions last year at nine major U.S. utilities asking for reporting on their exposure to the forces driving a 2 C transition – regulatory, technological, legal and meteorological. Ten large institutional investors controlled one of every three shares voted, but only one of them consistently voted to support increased climate risk disclosure. Three of the biggest (by shareholdings) voted against all nine resolutions, even as they profess a commitment to engagement on environmental (and other social, environmental and governance) issues and, in one case, sent public letters challenging CEOs of major corporations to explain how their company is “navigating the competitive landscape, how it is innovating, how it is adapting to technological disruption or geo-political events.”

How can we close the disconnect between stated intent and actual behaviour? Following the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TFCD), a group of three large Canadian pension plans called for enhanced climate disclosures from Canadian companies. The $270 billion Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec has gone further, pledging to increase its climate solutions investments by 50 per cent and reduce its listed company carbon intensity by 25 per cent.

We know that, notwithstanding concerns about the lack of well-developed standards and potential legal liabilities, climate risk disclosure is being implemented. A recent survey of 15 of the largest oil and gas companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange revealed that, taken in the aggregate, all but one was reporting on each of the 11 disclosure recommendations made by the TFCD. This suggests that such disclosure is feasible if companies, investors and the financial sector are interested in translating climate-related issues into financial costs (and opportunities). In Canada, examples of energy companies engaged in such reporting include Canadian National Resources, Cenovus, Devon Energy, Husky Energy, Suncor and TransAlta.

At the recent launch of a federal Expert Panel on Sustainable Finance, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney noted that “Canada’s financial sector has all the building blocks to make sustainable finance a competitive advantage.” Yet, in the same week, the Canadian Securities Administrators released a report calling for more study and monitoring before implementing disclosure requirements, even on a “comply or explain” basis. By requiring such disclosure by publicly listed companies of their scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, the U.K. boosted disclosure levels from 50 per cent in 2012 to over 90 per cent today, with improved comparability of data. Disclosure of scope 1 and 2 GHG emissions is now considered critical information by a growing number of investors. Ironically, absent comparable disclosures, they are relying on consultant estimates, which tend to overstate the electricity-related emissions of Canadian companies (largely powered by renewable energy).

Article 173 of the French Energy Transition Law requires that publicly traded companies, banks and credit providers, asset managers and institutional investors provide disclosure on climate change physical risks, as well as an explanation and justification of the disclosure methodology used. The European Commission’s recent action plan for sustainable finance sets out its agenda for upcoming actions covering all relevant actors in the financial system. This includes establishing a unified classification system to define what is sustainable and identify areas where sustainable investment can make the biggest impact, creating labels for green financial products on the basis of this classification system, incorporating sustainability in prudential requirements for regulated financial institutions and clarifying the duties of asset managers and institutional investors to take sustainability into account in the investment process and report thereon.

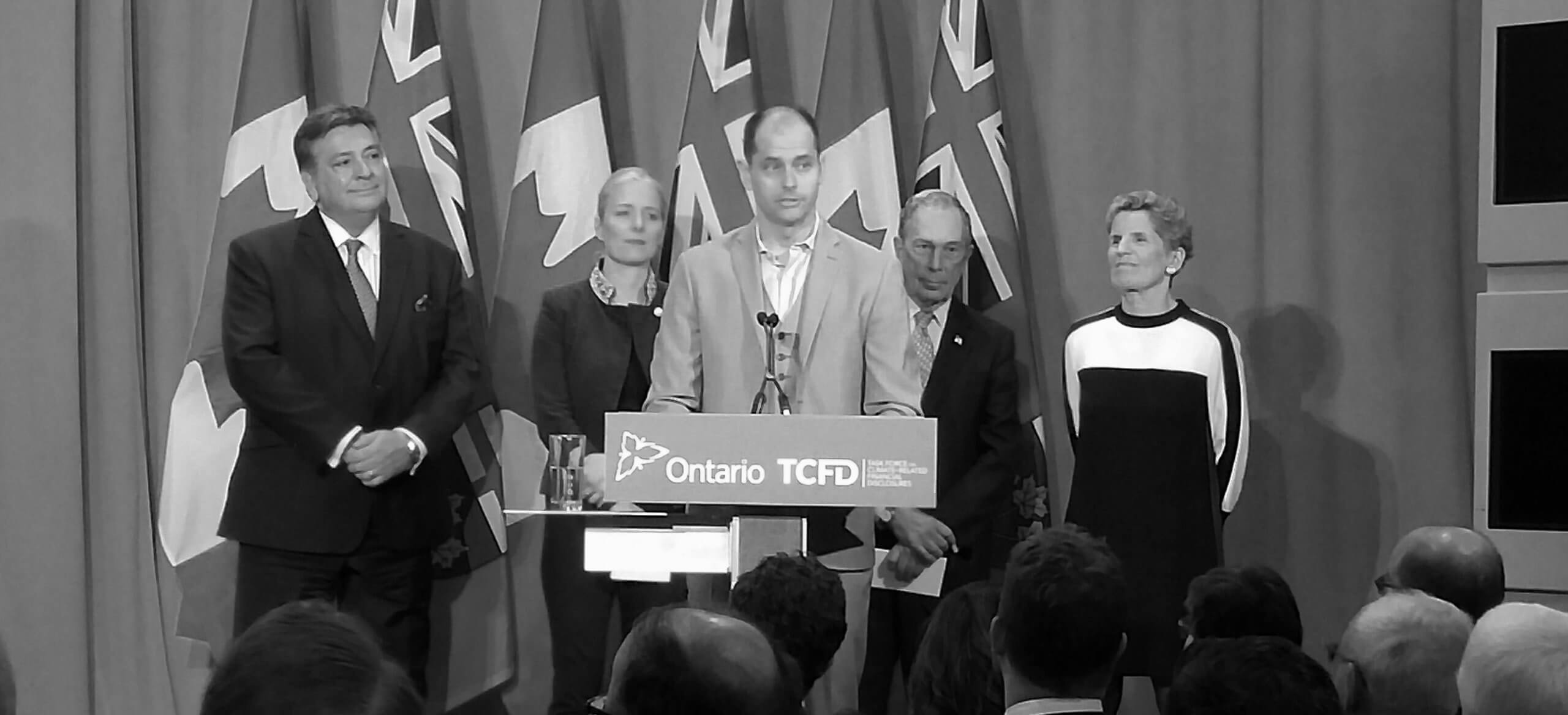

It is in this context that Ontario Premier Kathleen Wynne’s recently announced support for enhanced climate-related disclosures for publicly traded companies, asset owners and asset managers – as well as her commitment to work with the TFCD and the Ontario Securities Commission to strengthen the ability of the province’s financial sector to respond to climate change – is welcome news. Also welcome is the formation of the federal expert panel around the same time, which raises the possibility of coordination between the two levels of governments on this issue.

Countries with significantly less skin in the energy game have concluded that it’s time to better enable their citizens to evaluate climate-related risks on their savings. It’s hard to imagine why Canada wouldn’t follow this lead, if not take it.

Edward J. Waitzer is a senior partner at Stikeman Elliott LLP and a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School and the Schulich School of Business.