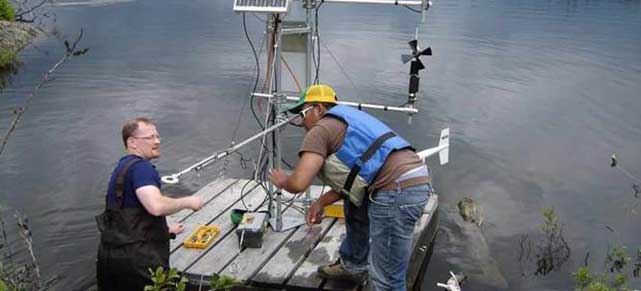

April 14 was a low point for science funding in Canada. That’s when the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD), with hat in hand, launched an Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign so it could restore the 46-year-old Experimental Lakes Area freshwater research facility in Ontario to its former glory.

The Canadian government, you see, withdrew funding from this world-class and globally unique facility a year earlier. The move was widely condemned by the scientific community, but with support from the Ontario government the IISD stepped in to keep the facility and its laboratories operational.

Unfortunately, this was merely keeping it on life support. Financial support for research was still at a bare minimum. In response, IISD’s crowdfunding campaign aimed to “rebuild the program to its former status” and, ideally, reduce reliance on government support “so that it may never again be shuttered because of changes in policy.”

It was good news when IISD reached its goal of raising $25,000, but the campaign didn’t solve the larger problem of underfunding scientific research in Canada – indeed, around the world. I thought the IISD campaign was somewhat distinct, but since then I’ve noticed more and more scientists reaching out to the “crowd” to fund research that has been rejected by government funders.

Just last week Mohammed Muhaymin, a researcher at University College London, contacted me regarding research he is doing into algae as a source of electrical energy for cities. The university wouldn’t fund it, so he launched a campaign on Indiegogo. “This campaign needs all the help it can get,” he told me.

A day later, I read a guest article on the site IFL Science from Tim Birkhead, a professor at the U.K.’s University of Sheffield. He wants to do a long-term study on guillemots, a type of seabird whose population in Wales was devastated by storms in February 2014. Natural Resources Wales cut funding for such research a year earlier. I went to Birkhead’s crowdfunding site, only to discover that the university has embraced crowdfunding in a big way for supporting all kinds of research projects.

I then searched Indiegogo and Kickstarter, two of the more popular crowdfunding sites, and found all kinds of research initiatives asking for support from the public. Most of them lament the lack of government funding for their research.

There are parallels with public education funding, which is also declining on a per-student basis. Speaking as a parent, public schools these days never pass up an opportunity to fundraise – whether it’s to pay for new books, air conditioners or classroom computers. Bake sales, book sales, dress-down Fridays, pizza day, pajama day, and hat day are among the ways parents are being asked to micro-finance what should be classroom essentials covered by government taxes.

Similarly, it looks like more and more scientists have no other option than to go directly to the public. It’s why three U.S. researchers decided in 2012 to launch a science-specific crowdfunding website called Microrgyza, which was re-launched as Experiment.com this past February.

“Since 2010, 80 per cent of principal investigators spend more time writing grant proposals and 67 per cent are struggling with less funding,” the site states, declaring that “Big Science” has become synonymous with “budget cuts.”

Experiment.com, it states, “is about Science for the people, by the people.” To date it has been used to launch 582 projects, of which 212 were fully funded and 309 failed. All told, it has raised about $1.2 million so far in the name of scientific exploration.

But it’s still very early days, and the way scientists engage with the public is bound to evolve. Nick Dragojlovic, a Vancouver-based science communication researcher, wrote recently on his blog FundedScience.com that the emphasis on specific projects is the wrong approach to take. Scientists, instead, should focus on building an Internet fan base that’s willing to support their longer-term research efforts.

“This type of strategic online engagement needs to become a mainstream activity in the scientific community,” wrote Dragojlovic, advising scientists to get savvier with social media. He cited data from a Nature News survey showing that only 13 per cent of scientists use Twitter regularly.

“Whether scientists use niche crowdfunding portals or the growing number of university-hosted crowdfunding websites, researchers’ online networks and public outreach are crucial to their ability to attract donations to support their research.”

This isn’t without its risks, however – particularly as far as the giving public is concerned. How, for example, do average folks determine whether a particular research project or scientist is legitimate? If it or she (or he) has failed to get government funding, is there a good reason for that? For Jeanne Garbarino, director of science outreach at Rockefeller University in New York City, credibility is a big issue.

“Anybody can use the Internet to push out their own agenda, whether it has integrity or not,” Garbarino said during a 2013 presentation at the New York Academy of Sciences. “If someone packages their project in a creative way, offers interesting rewards and then tries to sell it to a community that might not be able to discern whether it’s real or quackery, there’s a real problem.”

Many crowdfunding sites scrutinize projects to make sure they’re not junk, but how deep they go and how competent they are is largely a mystery to citizens looking to give. Garbarino said one solution would be to only accept projects that have been pre-vetted by a university.

Another question: Would crowdfunded science boil down to popularity contests, with the most money going to the sexiest projects and most attractive and charismatic researchers – that is, the rock stars of science? Or, would funding be more linked to how relevant the research is to the individual funder – e.g. a skin cancer survivor funding skin cancer research? In both cases, money might not flow to where it is most needed.

Finally, there’s the question of enabling the habit that governments have of offloading their core responsibilities, as many have done with education funding and other essential services. In other words, the more weight the crowd appears willing to carry the easier it gets for government to pass the buck. Social activists have similar concerns with regard to social impact investing becoming a transfer of responsibility from the public to private sector.

All of that said, the potential that crowdfunding has to positively boost science is undeniable, if for no other reason than because it helps to demystify the funding process and engage a public that has largely be left out of the funding loop.

“What would this world look like if every scientist touched a thousand people each year with their science message?” asked biologist Jai Ranganathan in a commentary for Scientific American. “One thing is for sure: a world with closer connections between scientists and the public would be a better world. And crowdfunding might just help to get us there.”

It’s just a shame we have to embrace it with so much desperation.