Last week, the federal government approved a US$7-billion takeover by Swiss-based Glencore of the steelmaking coal mines of Teck Resources, in a deal it hailed as a long term measure providing “generational assurance of sound environmental stewardship.”

But conservation and financial experts say that conditions of the approval are inadequate to protect the Elk Valley in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, where the company’s mining operations have for decades released high levels of the mineral selenium from waste rock into local waterways, harming fish populations and raising human health concerns.

“Teck is walking away from an unprecedented environmental disaster, with a windfall of billions of dollars,” says Casey Brennan, conservation director with the B.C. environmental group Wildsight. He says the company has been let off the hook for this water pollution by the decision last week by Innovation Minister François-Philippe Champagne to permit the takeover by Glencore. “It’s a pretty sweet win for Teck to be able to get this approval out of the minister like this with some very limited language that has very unclear legal implications.”

Simon Nicholas, steel industry analyst for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (a global network of energy transition analysts), says it will be difficult for the government to hold Glencore accountable for Teck’s environmental record with its plan to transfer control of the mines to a new coal company. “It’s hard to see this as progress given that Glencore’s intention is to spin off its coal operations,” Nicholas says.

The new company – focusing solely on coal production, in contrast with both Teck and Glencore, which are large diversified mining and metals companies – will face big risks as the world moves away from coal-based steel and power production, raising the possibility it could go out of business before the cleanup costs are met. “There ought to be concerns about whether the new entity will be able to afford long-term rehabilitation,” Nicholas says.

Teck is walking away from an unprecedented environmental disaster, with a windfall of billions of dollars.

– Casey Brennan, Wildsight

The federal approval, announced late last Thursday during a week with major summer holidays in Canada and the United States, was the last hurdle for Glencore and Teck to finalize the deal, expected to close July 11.

Under the approval, Glencore has committed to paying $350 million in rehabilitation and closure activities over five years to reduce selenium pollution in the Elk Valley watershed.

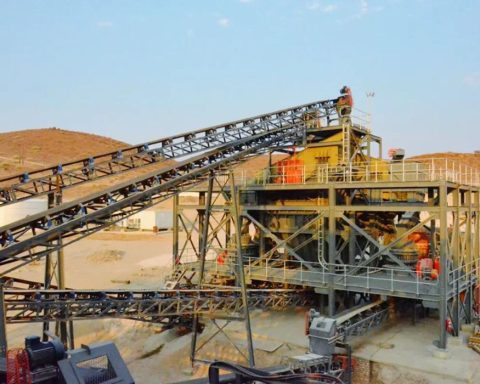

Teck has spent $1.4 billion since 2014 and will spend up to $250 million this year on water treatment. It has also posted a reclamation bond of $1.9 billion with the Government of British Columbia to pay for future environmental liabilities.

According to the B.C. government, Teck’s water treatment facilities are removing only a small fraction of the selenium in the Elk River, especially when spring and summer rains wash large amounts of the mineral into waterways from the man-made mountains of waste rock at the company’s open-pit coal mines. This means that despite Teck’s spending more than $1 billion on water treatment, selenium levels remain more than 200 times higher than what’s considered safe for aquatic life.

Cleanup estimated at $6.4 billion

A consultant commissioned by Wildsight (a conservation organization working extensively in B.C.’s interior) recently estimated the cost of cleaning up the pollution at $6.4 billion, which is almost as high as the total value of the takeover deal at US$6.9 billion.

In his statement announcing approval of the deal, Champagne said Glencore will maintain responsibility for payment of any environmental obligations through to 2050, including if the company is sold to another party. “Glencore’s commitment will result in generational assurance of sound environmental stewardship of the asset, regardless of future ownership,” Champagne said.

Glencore released a list of commitments it is making as conditions of the approval, including promises to maintain Canadian office and staff, donate to community organizations, honour existing agreements between Teck and Indigenous Nations, work with local Indigenous Nations, and increase Indigenous benefits.

The company also pledges to cover Elk Valley environmental obligations over the course of its ownership and potentially beyond. Glencore is committing to obtain prior approval from the minister on a mechanism to cover its obligations if the company is sold, or to continue to stand behind such obligations itself until 2050.

But these assurances don’t satisfy Wildsight, which would have preferred to see upfront reclamation bonds posted in addition to the existing $1.9-billion bond to the provincial B.C. government. “We will continue to press for greater levels of bonding, at least three times higher than what the provincial government is pulling out,” Brennan says. “It really is the only assurance at any level that things will be done and managed properly.”

Brennan says that a decision by the International Joint Commission to investigate pollution in the Elk River watershed could create pressure for a faster cleanup. The issue has become a problem for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and U.S. President Joe Biden because of objections from the Ktunaxa Nation, an Indigenous community on both sides of the border.

Last week’s decision also contains some stringent guidance on foreign takeovers of critical-minerals businesses, but this was unrelated to the Elk Valley takeover since steelmaking coal is not considered a critical mineral under the new federal rules.

The sale of the Elk Valley mines to Glencore will permit Teck to focus on its copper and critical-minerals businesses which are in high demand with the climate transition, as well as buy back US$2 billion of its own shares. “The large majority of its funds from the sale will be used to buy back shares in order to maximize returns to shareholders and will do nothing for local communities and contaminated waters that they’re leaving behind after billion-dollar profits,” Brennan says.

Eugene Ellmen writes on sustainable business and finance. He is a former executive director of the Canadian Social Investment Organization (now the Responsible Investment Association).