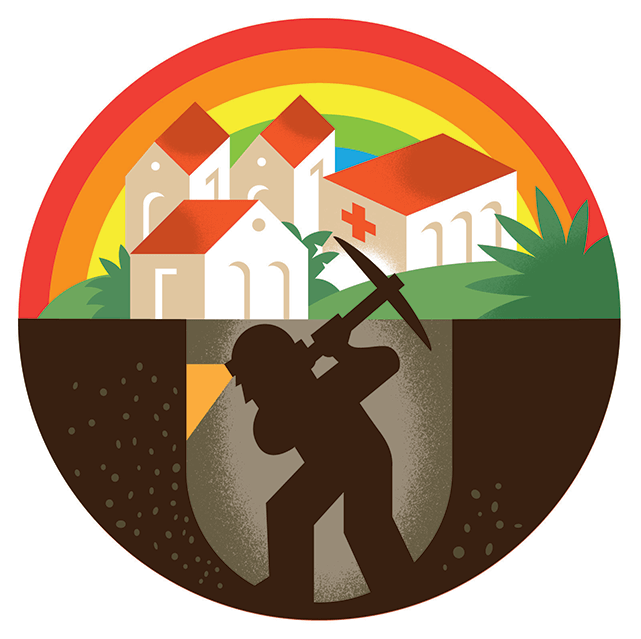

Barrick Gold, the world’s largest gold mining company, has made big commitments to improve the lives of Chileans living in the country’s Atacama region, the location of its controversial Pascua-Lama project. The company has funded a wide variety of projects, including development of a rehabilitation centre for handicapped children, a housing project, and the delivery of wireless Internet access to the area’s remote villages.

The company isn’t spearheading these projects on its own. Instead, it has relied on developing close partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and local institutions in the affected communities. “What we recognize, by using this approach, is that we are good miners, but when it comes to meeting needs in terms of education or of health, we do not have this expertise,” said Rod Jimenez, Barrick Gold’s vice-president of corporate affairs for South America, during an interview at his office in Santiago, Chile’s capital. “It is better to go with NGOs who have this expertise.”

By working with local organizations that are familiar with the situation on the ground, Barrick says it ensures that the projects it funds are adapted specifically to the needs of these communities, thus increasing the projects’ chances for success, and, in the end, improving the reputation of the corporation itself.

“From a business perspective, that is what ensures the sustainability of a business model,” added Jimenez. “We’re not in the business of building one mine; we’re in the business of building many mines. If you do the right thing, then when you go and build the next mine, that legacy follows you.”

But the “legacy” that follows Barrick Gold might not exactly be the one Jimenez has in mind.

Indeed, the business model – increasingly shared by North American mining companies – has become a matter of intense concern for local observers. Many fear that as the number of partnerships between the industry and local organizations increase, NGOs, who have traditionally represented civil society as a crucial counterweight to government and private sector interests, might soften their stance in the public debate on the social and environmental impacts of large-scale mining. Such partnerships are often perceived as a form of “co-optation” – a way for companies to more easily navigate through the more than 160 environmental conflicts currently registered on the South American continent. Through these partnerships, mining multinationals ensure that the NGOs and municipalities they financially support will be more inclined to stand alongside their decisions, effectively severing civil society from its main spokespersons.

Lucio Cuenca, director of the Latin American Observatory of Environmental Conflicts (OLCA), shares this concern. He points to Barrick’s Pascua-Lama project, which instigated one of the most widely covered environmental conflicts in the media over the last decade. “What Barrick did is block an entire sector of the population’s potential for mobilization, and to co-opt other sectors, through promises of employment, economic benefits, sums allocated to the municipality for local projects, and establishing parallel aboriginal organizations from those which oppose the project,” he said.

Cuenca deplores this tendency for mining companies to convert their public image to one of a “social actor” through such partnerships. It’s a conversion made possible by the confusion between philanthropy and economy, as suggested by University of Buenos Aires professor Diana Mutti, who with colleagues published a study on the issue this summer in Resources Policy journal. It specifically addressed the corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives of mining companies in Argentina.

“There are complexities in identifying whether contribution to local development is part of economic or philanthropic responsibilities of companies,” the authors wrote. “Mining companies substitute contribution to local economic development by increasing philanthropic activities, as managers admitted.”

Under the pretext of holding local communities’ interests at heart, many mining companies manage to dangerously expand their private sphere of influence to the public sphere, thus increasing the perception, the authors contend, that CSR is nothing less than “a manipulation tool” used to “undermine civil institutions” with the objective to “reduce community resistance.”

The case of the Renacer (Rebirth) project in northern Chile is a concrete example of this phenomenon. Recently inaugurated in a suburb of the mining town of Copiapo, this residential complex will welcome 125 families from slums in the area. The project emerged from a partnership, signed in 2008, between Barrick and Un Techo para Chile (A Roof for Chile), a local NGO whose mission is to eradicate shantytowns in the north, replacing them with adequate housing.

“Slums spring up here because of the high demand for labour in the mining industry,” said Daniel Gallardo, director of Un Techo para Chile. According to Gallardo, three Canadian projects alone – Maricunga (Kinross), Cerro Casale (Barrick) and Pascua-Lama (Barrick) – will require no fewer than 15,000 new workers between now and 2014, which could mean an influx of up to 45,000 people. “The objective, both for us and for the ministry of housing and urban planning, is to prevent exponential expansion of these camps,” he said.

It is not surprising that Barrick decided to provide financial support for the Renacer project. After all, it is in great part its own future employees who are now looking for a roof. The catch is that the Cerro Casale project, which has been shelved recently due to substantial capital requirements, is very likely to be met with resistance from the surrounding farming communities. In fact, this megaproject, which is located 145 kilometres southeast of Copiapo, will pump more than 900 litres of water per second during its exploitation phase, in a region known for severe drought. Indeed, on April 22, only a few days prior to International Earth Day, Chilean authorities declared a state of emergency on the Copiapo River watershed. After two decades of overexploitation in the mining and agricultural industries, the basin has virtually run dry.

Barrick Gold has consistently denied that its activities in the north of Chile could have any material impact on water resources in the region, where its Pascua-Lama and Cerro Casale projects reside. In the latter case, the company insists that the totality of its freshwater consumption will be drawn from outside of the Copiapo River basin.

A great deal is at stake, as the drying up of water reserves in the region’s valleys, upon which thousands of farmers depend, could result in a new rural exodus toward urban centres like Copiapo. These populations, displaced by depletion of water sources, would be added to an already overwhelming influx of mine workers from the south.

Gallardo is no stranger to this problem. “There are many valleys that are being closed down due to water shortages,” he said. “All of this labour force will sooner or later have to move toward the cities to find work. This is a problem.”

But when asked if the mining companies’ consumption of enormous supplies of water is in part responsible for this exodus, Gallardo was evasive. Given the fact that his organization is sponsored by these very mining companies, is there a risk that his point of view may be biased in public debates concerning this type of mining in desert areas?

“If we are in the eventual position where we must take up opposition to bad practices, we will do so,” he affirmed. “However, there is another important theme: families. We recognize that the environment is important, but we also believe that families have the right to live under a roof, in dignified conditions. And if we are in need of financial support from a mining company, we will accept it.”

The case of Un Techo para Chile is emblematic of this tendency. Through direct contact with families that migrate toward urban centres, the NGO is a front-line observer of the social and environmental impacts of the mining boom in the Atacama region. However, its numerous partnerships with mining companies place the organization in a predicament in which it may be discouraged from taking a public stance on the very problem it is supposed to be fighting: temporary housing sprawl. Citizens therefore find themselves without one of their primary representatives in the debate on the social and environmental costs that are generated by this industry. For its part, the NGO finds itself stuck treating the symptoms of the mining boom – the slums – without being able to publicly address the origin of these symptoms – the mines.

The drying up of the Copiapo River risks drawing significant attention to mining sites in the area, such as Cerro Casale. Many observers are challenging authorities’ consistent approval of such mining projects, considering the fact that inhabited zones are already facing water shortages. They wonder why NGOs and local institutions are being boosters of such projects instead of openly questioning their value.

“Stakeholders perceive that the increase in philanthropic activities does not compensate for reduction in environmental and ethical responsibilities,” wrote authors Natalia Yakovleva and Diego Vazquez-Brust in a 2011 study published in the Journal of Business Ethics. As long as North American mining companies fail to give adequate weight to their environmental responsibilities, the public’s perception will be that this philanthropy is merely a way to deflect communities’ attention from the real issues.

In this context, partnering NGOs run the risk of being perceived as accomplices in this deflection effort. They risk losing credibility with the public they were created to represent and defend.

Latest from Energy

OPINION | With a few actions, we could save tens of terawatt-hours of electricity by 2028

Nature distributes risk. Clean energy can, too – and in doing so, deliver a safer, fairer,

A subtle repositioning of the IEA’s energy demand scenarios could have enormous consequences for the energy

In 2025, Canada's government-owned pipeline abruptly switched from losing money to posting profits. The secret? Hide

The capture of Venezuela’s dictator inspired some jubilation and much distress across South America