Corporate Knights’ Trading Places CEO Exchange Project is designed to give NGO and corporate chief executives an opportunity to walk a day in the other’s shoes. The idea is that if both parties have a fuller appreciation of each other’s perspectives, it will be easier to overcome adversarial positions and come together to form solutions, where it makes sense. In 2004, Corporate Knights organized two exchanges: between Frank Dottori, CEO of Tembec Inc., and Beatrice Olivastri, CEO of Friends of the Earth Canada; and between Monte Hummel, CEO of World Wildlife Fund Canada and Scott Hand, CEO of Inco Ltd.

Monte Hummel is trying hard not to laugh. He’s sitting in the corporate boardroom of the International Nickel Company of Canada, with his scraggy haircut and chops, they with their starched shirts and cufflinks. And Monte’s got a big problem. He has a meeting with Walter Curlook, bigwig at Inco, a company Monte refers to as ‘Stinco,’ and doesn’t know how he’s going to be able to take him seriously.

In the early 1970s Monte and his coterie of environmentalists raised quite a muck over an Inco-sponsored pollution fiasco centred in Sudbury. Feeling the heat from the negative publicity, Inco agreed to meet them and try some damage control. Curlook leaned over and said to Monte, “You know, I have a horse named Monte,” to which Monte replied: “Oh yeah? I have a dog named Walter.” You can imagine how the meeting went.

Today things are different. Inco still has its fair share of problems, but starting in the late 80s it dramatically reduced its sulphur-dioxide emissions. Even Greenpeace has had some good things to say about the century-old company with a checkered past. With a presence in 40 countries, Inco is the world’s second-largest nickel producer.

Scott Hand, the current CEO of Inco, is a company man. He’s clocked 32 years of service. He worked his way up the ladder. He gets driven to work in a beige sedan. He’s got the house in the hills where he and his wife throw society parties.

Unlike a lot of other bigwig TSX CEOs, Scott has lived in an Ethiopian village for two years as a member of Peace Corps in the 60s. He’s got something else going for him, too. He’s a little bit curious. In this case, he’s curious about how the other side works.

Scott has a reputation for being a rational, focused man who puts emphasis on facts. So his approach to Trading Places was pragmatic—to go in and learn as much as he could, while making sure Inco scored some good PR points in the process. Perhaps also Monte could bring some of his emotio-ecological quotient (environmentalist EQ) to help Inco with some of their sticky issues. Scott was going to make a good time out of it, too. “I think Monte has nice teeth,” he quipped. “I’d like to try the WWF dental plan for myself.”

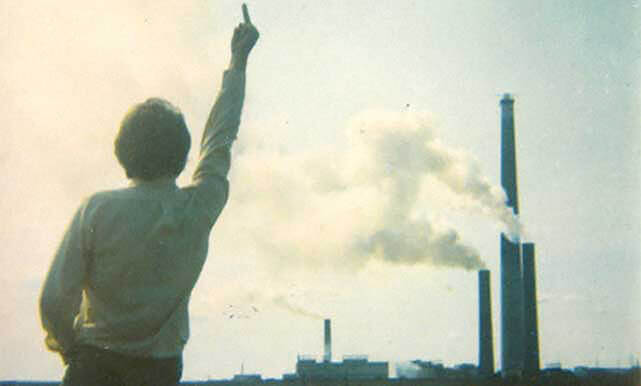

Monte is Canada’s most charismatic environmentalist, bar David Suzuki. A few decades ago, the proud son from Whitedog Falls, Ontario, was sticking his finger up at smokestacks. Today he probably still does—he just doesn’t pose for it. Hovering just under 60, he’s a few years Scott’s junior, but they both could pass for mid-50s. He’s clocked his quarter-century plus of service. He helped found Pollution Probe back in 1969 and has been the head of WWF Canada since forever. He drives himself to work in a Toyota Prius. He throws barbecues with his wife Sherry.

It took only one telephone call to get Monte on board with Trading Places. He called back the next day and said, “I’m in.” (In Scott’s case, it took a couple of meetings with his advisors and some backchannel phone calls to get the nod.) Monte was looking to get three things out of the exchange. First, what better way to cap his final year as president of WWF Canada than to take over the company that he first berated? Sort of like the canary inviting the cat into the cage. Second, it was an excellent opportunity to further his ongoing White Hat pet project (see sidebar). Third, he wanted to solidify Scott’s support for his Boreal Forest Conservation Framework, another pet project (see sidebar). Well, maybe there was a fourth thing. The WWF could siphon off some of Scott’s financial acumen.

WWF Canada is part of World Wildlife Fund, the world’s largest independent conservation organization. With its cute panda bear logo, the WWF publishes an annual Nature Audit of Canada, and pushes for the creation of national parks and the expansion of other protected areas. It recently cemented an agreement with Lafarge North America Inc. to protect Rocky Mountain grizzlies, wolves and cougars. It works with forestry companies to adopt sustainable forest practices. Sometimes, it even lends out employees to forestry companies to help implement the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification. It has a $16 million budget and 50,000 active Canadian supporters.

And, one day in May 2004, WWF Canada was run by a nickel company CEO.

The exchange

Monte and Scott met for breakfast at the Park Hyatt Hotel in Toronto’s upscale Yorkville district, symbolically a half-way point between Inco’s offices on King Street West and WWF’s base on Eglinton Avenue East. Scott didn’t come alone. Inco’s contingent included PR man Steve Mitchell and some cameramen to capture the moment for posterity.

Environmental communications and government relations consultant Mark Rudolph was on hand to broker the summit. Rudolph is a confidante of both men. He is a former student of Monte’s at the University of Toronto and he now includes Inco among his roster of clients. Rudolph says he’s only interested in working with pragmatic environmental NGOs and progressive companies. “I don’t have time for the environmental purists and the corporate denialists.” As executive assistant to Ontario Environment Minister Jim Bradley in the 80s, Rudolph was instrumental in bringing about the Countdown Acid Rain Program, which required a 66 per cent reduction in sulphur dioxide emissions. Today he’s behind many of the environmental headlines. He prefers to take a ‘no footprints in the sand’ approach.

Monte had porridge with banana and two slices of rye toast; Scott, an English muffin. They made small talk. Monte told Scott how WWF had launched a lawsuit to prevent BHP Billliton’s Ekati mine in the western Arctic from going ahead before establishing the conservation-first principle. Former Canadian Prime Minister and WWF board member John Turner “was ready to don the robes and go to the Supreme Court on this one,” Monte told Scott. This time, there was no dog-and pony exchange. Both men acknowledged that they are accountable to their shareholders. Monte said, “We go to different capital markets, but the idea of being able to show to your shareholders or to your supporters that you’re actually delivering something, is something we have in common.”

The breakfast went much better than Monte’s first meeting with an Inco executive some 30 years ago.

As they left the Park Hyatt, Monte told Scott to “take care of my baby,” to which Scott replied, “you take care of mine,” before riding off in Monte’s Prius, driven by Monte’s assistant. Monte then jumped into the chauffeured beige CEO-mobile. The door was opened and shut for him.

Scott at WWF

Inside WWF, on his way to Monte’s office, Scott bumped into a WWF staffer who plays tennis at the same club as him, a sign of the converging worlds.

In his new office, Scott noticed a stack of business cards, on which Monte had scratched out his own name and scribbled in Scott’s. There was also a pin, which read “Keep mining green in Canada.”

The first thing Scott wanted to do after he got his bearings at WWF was to call Monte up and make sure that he wasn’t breaking the bank over at Inco. When no one picked up the line, Scott wondered aloud if Monte had already gone for lunch. But then someone picked up, and Scott asked to speak with the new CEO at Inco, Mr. Hummel. While waiting for Monte to accept his call, he cupped the mouthpiece and whispered to us, “I just want to make sure Monte isn’t spending too much money.” At the same time, he was also asking around for Inco’s stock quote and wanted to know the current spot price of nickel.

Scott’s first meeting of the day was a briefing by senior staff of WWF, Steven Price, director, forests and trade program and Dr. Peter Ewins, director, Arctic program. Their job was to bring Scott up to speed on the organization’s approach to corporate partnerships and prepare him for the big Canadian Boreal Initiative meeting later that morning. It was a crash course in ecological conservation, complete with a Ph.D, colour-coded charts, reports, a nature audit, and whiteboard lecture notes. Scott was impressed by Ewins and Price’s command of the facts, even as they machine-gunned him with terms like dynamic equilibria’ and ‘three-legged stool of conservation.’ The WWF team was gearing up for some serious work sessions and the Inco chairman knew he was not there to punch the time card. It set the tone for the day.

Price made a point of identifying WWF’s approach for Scott: “We’ll work with any partners we need to to achieve our goal. Sometimes that’s mistaken as [being] moderate. It’s not. It’s radical.” Some NGOs think that working together with companies is like doing a deal with the devil. WWF doesn’t care as long as it helps them get to the finish line more quickly. As Price explained to Scott, WWF concluded that it was not enough to lobby government alone. Sometimes, they decided, they could make more conservation progress by dealing directly with their former enemies. “The forestry industry has undergone a huge evolution over the past generation. They see what happened to the fisheries and they understand the need to conserve nature so the wood supply is there for the long term,” Price explained.

WWF Canada convinced forestry giant Tembec Inc. to set aside some land as a no go conservation zone and to adopt a sweeping commitment to bring all its forests up to the FSC specifications. In return, WWF agreed to help create marketplace value for Tembec’s wood and paper, including giving Tembec the use of the WWF logo. The initial dividend for Tembec, aside from an energized staff, was a $120 million contract with Home Depot. But WWF is worried that Tembec is not getting enough return on their FSC investment.

But Scott was skeptical about Tembec’s no-logging zone pledge. “Has Tembec done that?” he asked. When Price confirmed that they had, Scott gave a pensive nod. While Tembec is their flagship forestry company, WWF has also encountered varying degrees of success lining up conservation agreements with tree topplers Domtar Inc., Abitibi-Consolidated Inc. Norske Skog Canada Limited and Alberta Pacific. The oil and gas sector, however, has not been as eager to play ball with the conservation group. In explaining their approach to the proposed $7 billion Mackenzie Valley pipeline, Price parlayed, “we are not anti-pipeline. It’s about getting conservation lands and plans put in place first.”

This contrast piqued Scott’s curiosity: “what is it that made them say we cannot put a model of conversation first?” The forest industry is more sensitive to these types of concerns because it’s more visible. “Oil and gas hasn’t felt anything like the European boycott of Western Canadian lumber in the late 80s,” Ewins pointed out. In other words, they have more to lose from an environmental backlash.

At 11 am, Scott presided over a high level panel of Canada’s leading conservationists to discuss the Canadian Boreal Initiative (CBI) around WWF’s hemlock boardroom table. A Placer Dome executive was also in the room. The mission of the meeting was to figure out how the CBI can enlist the support of the mining industry to set aside 50 per cent of Canada’s boreal forest as a development-free zone.

Most of what remains of world’s boreal forests is in northern Canada and Russia. Canada has a unique opportunity to strike the right balance between conservation and development in advance because the northern forest is pretty much untouched.

According to WWF, the problem with ‘conservation first’ is that it is usually not done first—too often it’s an afterthought. The CBI offers a chance to get things right from the get-go. The CBI is of the view that humans can and should use land in a sustainable way that generates economic benefits. But some environmentalists say any development is too much. This position has a hint of cultural hubris, as it takes a big opportunity for economic development off the shelf for the four million Canadians, many of them aboriginals, who inhabit the area.

The ‘50 per cent for conservation, 50 per cent for potential development’ approach adopted by the CBI, which includes substantial environment groups, industry and aboriginal membership, seems a sensible halfway point. However, long-time environmental advocate and former federal minister of the environment Charles Caccia opposes the CBI because he sees it as giving carte-blanche for developing the 50 per cent that is not protected.

At the end of the day, the government, which owns the majority of the land in question, will have to accept the framework if it is to become a reality. Since the boreal region has many trees and oodles of minerals, the two most natural opponents of such a measure are the mining and forestry industries.

After a brief preamble, the meeting quickly got to the point: “What would it take to have the mining sector endorse the Boreal Conservation Framework?”

Despite the participants’ past differences, the meeting started out on a hopeful note.

Alan Young, the representative from CBI, tried to put it in perspective. “I helped set up Mining Watch,” he looked at Scott, “you’ll be thrilled to know.” Scott grinned. “There have been significant changes in the mining sector. That’s why I’m here.” Young maintained that the CBI is a “100 per cent solution that addresses ecological, cultural, and economic imperatives.”

Young also threw down a gauntlet. “There will be some conflict areas—hotspots—where we’ll have to use our leadership capacity to get beyond,” foreshadowing the fight that was about to happen. He was referring to the scenario in which an extremely sensitive ecological zone contained a mother lode of minerals, with both sides staking their claim.

Scott crossed his legs and asked, “Protected areas means ‘Thou shall not develop?’” It slowly dawned on him. “I can see then why the mining industry might not support that. Only the Good Lord knows where the minerals are.”

Mark Rudolph explained, “We can do one of two things: if we preach ‘Thou shall not do mining,’ we’re not getting anywhere. But the alternative requires a degree of flexibility on both sides, so there is a mechanism for the miners to get stuff out in a way that doesn’t violate the environmental and cultural principles.”

Scott took Mark’s cue and struck a conciliatory tone. “At some point, we have got to be able to let go of an area, and say, ‘there’s not enough here, it can be protected.’” It may come as a surprise to some, but Inco has already done this. Government officials told WWF that they couldn’t make a park because there was a large iron ore deposit right in the middle of the land. On WWF’s prompt, Inco, knowing the mineral potential was pretty low and not wanting to be the scapegoat, went over the top and said “We’re quite prepared to see that iron deposit be part of the park and never developed.” So the word of both WWF and Inco swung the balance.

So what happens when there is a spot of land that is valuable to everybody? A compromise, Rudolph proposed, would be a system of swaps. (Swaps are a mechanism where certain types of protected lands that turned out to be mineral rich might become eligible for development in exchange for another parcel of similarly valuable land becoming protected.) The devil, of course, is in the details, Scott noted.

Not seeing an easy way to broker the divide, Young voiced a frustration. “There’s not enough market pressure on the mining and oil and gas sectors to get them to do this.” Then he paused, and wondered: why couldn’t there be an accountability chain like there is with diamonds? “The CEO of Tiffany’s told me that ‘if 60 Minutes sticks the microphone in my face and asks me where my diamonds come from, I have to have the answer.’”

For industrial mining companies, the impetus to change comes from affected communities as opposed to consumer pressure. “We’re getting there, but it’s by a different route. It’s more about access to product, a social licence to operate,” Scott put in.

It was at this point Colin Seeley from Placer Dome, who’d been quiet for most of the meeting, stood up and threw a wrecking ball. “We can’t forget our economic system is driven by resources. If we make it unpalatable to mine, then our standard of living could decline.” Seeley objected vehemently about what he called the ‘sterilization’ of Canadian exploitable lands. “You’re limiting opportunities in this country,” he said.

Quickly, a WWF representative tried to steer the conversation back to safer ground, asking “Isn’t it helpful when companies get endorsement by environmental groups?”

But Seeley was unfazed. “We have to think beyond that. At some point, you [environmentalists] will have to compromise. Society has to understand that we have to cut down trees.”

Ewins shot back: “Some areas are nonnegotiable.”

Seeley dug in his heels: “That’s fine, but some of these discussions that take place in isolation with a narrow focus in absence of other information produce different decisions. By saying 50 per cent is off-limits, you have alienated land.”

Price had had enough: “I thought we were past all this. I thought this was a question of how and where—not if.” The stench of acrimony had seeped into the room and was filling every corner.

Scott broke the ensuing silence, stepping above the fray to try to put things in perspective: “The [Conservation] Framework has to recognize economic realities. If you make things too difficult, business will go where it can develop more quickly. But we’re not going to go where we’re not wanted. You might have been able to go where you were not wanted 20 years ago. You could go to Indonesia if Mr. Suharto said ‘Ok.’ Today you can’t do that. We wouldn’t be in Voisey’s Bay if the Inuit didn’t want us.”

By this time, Scott had earned his lunch so it was off to the Toronto Club to meet Biff Matthews, chairman, WWF Canada and Michael de Pencier, past chairman of WWF.

Monte at Inco

After taking the call from Scott, the new CEO of Inco settled into his first meeting of the day to discuss the legacy issue of Port Colborne, Ontario, with Dr Bruce Conard, vice-president, environmental & health sciences. This was an issue about which Monte knew just enough to be dangerous.

The story could fill (and probably has) a small warehouse with court documents and studies. The problem stems from elevated nickel levels in the Port Colborne community that are attributable to Inco’s local nickel operation, which, during the Second World War, was one of the largest refineries in the world.

It started out as a health issue because of high levels of nickel in residential soil and inside households. From there, the lawyers got involved, and, a couple of class actions later, the point of debate is about property values not health issues, Conard explained. Inco has acknowledged a degree of responsibility and has offered to truck out contaminated soil and truck in new soil for every affected household. It has also offered to bring in industrial vacuums to suck out the offending nickel from every nook and cranny in the neighbourhood.

But the lawyers have created a confrontational environment. On the side of the attorneys for the Port Colborne residents, the dollar signs beckon. On the side of Inco lawyers, the fear of precedent looms.

They are worried about future liabilities that might mushroom out of this case.

Monte surmised, “Negative press on this issue is a major contributor to the potential ‘grey hat’ perception of Inco. I believe that a little common sense and goodwill can change this environmental negative into a deserved positive for Inco. The good news is that the affected owners of Port Colborne and the company both want to resolve this matter, but the fact that it is before the courts is not helping. This may be a case where the lawyers on both sides are impeding a solution.”

Monte pointed out that Inco had too much to lose by not rising above the legal fray to reach a satisfactory solution (see sidebar for his recommendations).

Monte’s next meeting was with Mark Daniel, vice-president of human resources and Stuart Feiner, executive vice-president, general counsel & secretary, to discuss New Caledonia, Inco’s South Pacific project. Daniel and Feiner filled Monte in on some important details. “We’ve been trying to develop this property for over 50 years. This is not a quick in-and-out for us. We want to develop this world-class nickel deposit, but only in a way that enjoys the agreement and support of the people in New Caledonia.”

Monte had already been briefed on New Caledonia by WWF France, which has been keeping a close eye on this former French colony. A senator from New Caldeonia came to Inco’s AGM in Toronto last year to protest the development. Environmentalists are also concerned about the impact the project might have on the world’s second- largest coral reef. To complicate matters, the area could be declared a World Heritage site and, unlike in Canada, New Caledonia’s constitution—written by the French—precludes making agreements directly with the aboriginal population.

Daniel and Feiner explained the measures Inco was taking to address some of the concerns. Inco would not engage in deep water marine disposal of tailings and was committed to carefully monitoring effluent from the plant (especially manganese) in the adjacent lagoon.

Monte seemed pleased with these measures but cautioned that Inco should work with a range of other groups to ensure the conservation-first principle is protected, including agreeing to reserve areas that the residents want to see protected from industrial development.

Having set the agenda himself, Monte had to pack in one more meeting before lunch, this one on Inco’s climate change and energy conservation efforts with Dr Les Hulett, director, environmental affairs. Although Inco is still one of Canada’s most polluting companies, Les was pretty proud about the progress that it had made. He informed Monte that the company was ahead of Kyoto targets and okay with the Kyoto model of emissions trading, but that there was some uncertainty over whether it would get credit for its early action.

“A big part of Inco’s success in cutting back greenhouse gas emissions,” Hulett beamed, “was energy conservation on the back of an internal program, Powerplay, which is employee-driven. We asked our employees how we could conserve more energy, and they came back with over 700 ideas. Some of them were no-brainers like closing windows in the winter. Creating a sense of empowerment on the floor is key.”

Hulett’s passion for the environment was genuine and it impressed Monte, who nevertheless cautioned Inco not to stop or slow down now that they had “already picked the low-hanging fruit.” He also suggested that “companies need to talk more positively about Kyoto by communicating that they are doing good work toward Kyoto targets.”

Monte was less impressed about Inco’s view of the role of coal in Ontario’s mid- to long-term energy future. Inco saw a future for coal. Monte didn’t. They had to agree to disagree.

Near the end of the meeting, Monte and Hulett hit on the importance of the next 10 to 15 years as a transition period for a different way of doing business. Hulett asked Monte, “When are we going to have key people take a more holistic view of the future?”

On this note, Monte headed off for lunch with Ron Aelick, president, Canadian and UK operations and Stuart Feiner at Reds Restaurant in Toronto’s financial district.

Scott at WWF

Following lunch, Scott had a strategy session with WWF’s top brass. WWF chief bagman (aka vice president of public support) Dave Prowten opened things with some background, noting that this was a great time to talk about endangered species because the feds were ready to make this a priority. The WWF was about to sign a four-year deal with the feds and was looking to ink more such multi-year deals, getting away from one-year agreements. Arlin Hackman, vice-president, conservation, explained the WWF bottom line: “The most lasting core part of our business is recovering endangered species— the extent to which we can do that is our yardstick for success.”

The WWF had identified the mining industry as one of the key users of the landscape, and was “looking at how best to go after them to get support for recovering endangered species.”

On the side, Prowten asked Scott if he would be interested in printing Inco’s annual report on FSC-certified paper (something companies like ScotiaBank have already done) to help build demand for more responsible forest products. When Scott answered that it might be something of interest, Prowten (a straight-shooter if you ever met one) didn’t seem too impressed and said, “I can see it’s not top of mind.”

Scott had hung his jacket over his chair and the WWF pin was poking him in the back, so he adjusted his position and then offered some of his insights into the world of fundraising in response to a question from Hackman. “I am on the board of the Ontario Heritage Foundation. If I’m fundraising I’ll make a call to a bank’s chairman and ask them to support the foundation. I don’t know how effective that is, but a lot of contributions are made through the old boys’ network.”

But Scott noted that many companies were moving away from “just writing cheques.” Rather, it’s about finding a fit with each company’s employees and communities. In this vein, Scott suggested the WWF tailor their conservation programs to match what was relevant to companies.

While that might help the WWF’s finances, Prowten wasn’t so sure about how it would help the WWF’s real bottom line.

“We can’t force conservation criteria [based on how it fits into a company’s priorities] because it won’t be successful in the longterm.”

Scott retorted that, “Inco can’t give money to a marmot fund in Vancouver.”

Hackman took this opportunity to remind Scott of the relevance of this discussion to the morning’s boreal roundtable: “When you get to the point where we are now [in terms of the number of endangered species], it takes a fair amount of money to fix things. What we talked about this morning was the front end, or the cheap end. If you don’t get that right, then it becomes a lot more expensive.”

Scott’s mind was clicking. “So it’s like a liability. If you don’t get things right at the beginning it’s a lot more expensive to fix them in the end.”

Scott switched gears and started to talk about a National Geographic article about New Caledonia’s ancient trees. Given the number of countries that Inco and WWF both operate in, he wondered if there might be some opportunity for them to engage at a global level.

Prowten, who hadn’t said anything for a while, thought, yes. He suggested that WWF Canada make a map overlaying their priorities (and those of its sister WWF branches) with the areas of operation of their corporate partners. By virtue of geography, opportunities to save more species might be realized.

Scott nodded appreciatively, perhaps recognizing some of himself in Prowten’s global ambitions.

By this time, Scott was hitting his stride. He had started to consider the pros and cons of corporate engagement from an environmental organization’s point of view. With firsthand knowledge of how demanding big shareholders can be, Scott asked: “If Inco makes a big contribution to Pollution Probe, what does that do to them?”

“It’s tricky,” Prowten said.

Scott added hopefully, “I trust that corporate money is not going to affect your priorities and it shouldn’t. If it was like that I wouldn’t want to do that.”

Prowten saw where Scott was coming from. He said that WWF could help their corporate partners in ways that didn’t compromise WWF’s principles, notably by tipping the ‘white hat’ or by endorsing sustainable products like FSC wood. “That’s really where we would like to add some value, by moving the marketplace.”

Prowten’s creative juices were starting to flow. “What if Inco was to define and implement a world-class standard for one of its nickel operations? [call it the Mineral Stewardship Council (MSC)] Then that nickel could be used for a special series of Canadian nickel coins featuring endangered species on one side and the panda on the other.”

That would create positive awareness about how nickel is being mined and it would create a new market for Inco, which (as might come as surprise to some) doesn’t have a contract with the Canadian Mint for the nickels. A nickel for your thoughts, Dave.

Scott had filled up his Cambridge notepad, and it was time to retreat to his office and write up his recommendations after a hard day’s work as an environmentalist.

Monte at Inco

After a satisfying lunch on Inco’s tab, Monte had another hour with the company’s number two [Aelick] joined by Hulett and Nick Sheard, vice-president, exploration, to talk about biodiversity, or, more to the point, the CBI.

It was a similar situation to one that Scott had at the WWF in the morning. When Monte explained that he wanted 50 per cent of the boreal to be a protected area, which would mean no industrial activity including mining, Sheard felt compelled to contribute, “miners are not vandals.”

That was when Monte really started to talk as if he was CEO of Inco (although truth be told, he made the transition to corporate titan pretty smoothly; there was a mischievous glint in his eye whenever an Inco executive would attentively take notes on his instructions).

“There’s a way to conserve 50 per cent of the boreal region with virtually no netloss to Inco,” Monte punched home.

“But we’re talking about a pretty large scale here, about setting aside a quarter of the area of the whole country. I think even I can understand that presents some difficulties for an industry that needs and wants to have access to a large portion of the landscape for exploration purposes. You never know what might be found. And we know that exploration can be done these days with virtually no physical contact with the ground, with flyovers and the like. The mining industry can say, ‘Look, we have no problem with a huge portion of the landscape being in protected areas but we would hope that in a significant portion of that protected area we can at least take a look and if we find something that’s economically desirable, then maybe we can work out a no-loss policy where there’s a swap or something’s added somewhere else but we’re allowed to develop this part so that way we always have the same proportion of the landscape that’s protected but the company is given a break in terms of exploring and developing.’”

But this was something Monte knew would be difficult for environmentalists to swallow.

“When we go back to our supporters we have to say ‘Well, the good news is we got a new park today; the bad news is that there could be mining on it at some point in the future.’”

He continued, “Rather than say ‘Ok, Mexican standoff,’ we’re at war in perpetuity, I think we should look at the areas where we can collaborate and cooperate. In Manitoba, we’ve identified over 40 areas, adding up to about 4 million hectares where Inco has said they think the mineral potential here is so low that they would be prepared to support having these areas set aside with no mining activity.”

In other places, the creator has rather mischievously placed some valuable mineral deposits in some pretty choice ecological areas. “Rather than take an attitude of sworn enemies, I would rather try to engage; figure out how we can minimize our differences and what progress we can make, short of embracing each other and falling in love forever. Just because you can’t ultimately agree on getting married doesn’t mean you can’t date a little and you know, get some good stuff done.”

At the end of the day

Not all NGOs and companies can make dancing partners—or should. Companies have money, power, and influence. NGOs have public trust and the moral high ground. But non-tangibles have monetary value and power—perhaps more in the long-term. Interbrand valued Habitat for Humanity’s brand at US$1.8 billion. But it’s not really about money.

Even though they didn’t ask for it, NGOs are among society’s last bastions of public trust. If this reservoir is drained, it might never be replenished.

Time is not working in our favour and the stakes are too high. Companies and NGOs need to work together—not for the sake of working together, but with a calculated purpose that goes beyond putting a panda bear on a pizza box. We almost have to wish for a Mr Spock at the helm of either side of corporate-NGO partnerships. It’s the logical thing to do.