Rio+20, the UN Conference on Sustainable Development, is fast approaching and, by any measure, our global sustainability crisis is increasingly evident. As Achim Steiner, executive director of the United Nations Environment Programme, said in February, “That moment you were reading about or studying has arrived.” Steiner was speaking at KPMG’s Business Perspective on Sustainable Growth summit in New York City, where he posed a simple but daunting question: “How do we feed, fuel and employ nine to 10 billion people?”

A quarter of the world’s productive land is under the threat of soil erosion and nutrient depletion. Making matters worse, 40 per cent of agricultural production is never consumed as food, said Steiner. UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon’s high-level sustainability panel report, “Resilient People, Resilient Planet: A Future Worth Choosing,” indicates the annual irrigation behind wasted food is equivalent to providing nine billion people with water.

As current production and consumption patterns stretch the planet’s resources, the world population by 2050 will require two and a half planets. Developing countries are expected to account for most of the increased demand, said Karl Falkenberg, the European Commission’s Director-General for Environment, in an interview with Corporate Knights.

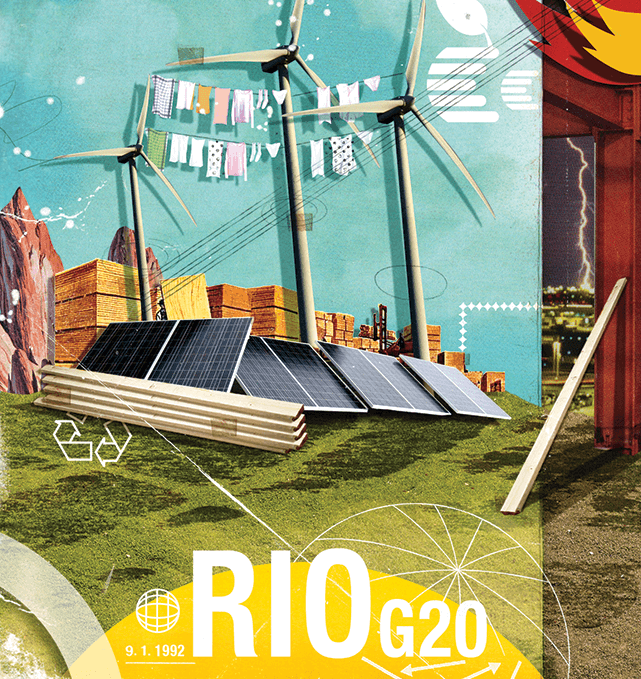

If we are to accommodate a growing population, Rio+20 must put the strong governance in place to deliver green, sustainable growth, said Falkenberg.

The legacy of Rio

Held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development, or Rio Earth Summit, was an “historic moment for humanity,” according to Maurice Strong, secretary-general of the conference.

It brought a new post-Cold War security agenda focused on development and environment and delivered new governance with the creation of UN bodies for climate change, biodiversity and sustainable development. Millennium Development Goals were set and sustainability was embodied in Agenda 21 (for the 21st century), a plan of global action that sought to make polluters pay, end global poverty and restore the earth’s ecosystems to health.

The Rio summit was a “huge success,” former Canadian prime minister Paul Martin told Corporate Knights. “Rio focused attention on environmental considerations in a way nothing else could have,” he said, underlining its “unprecedented” nature in gathering world leaders to discuss the environment.

Historic, yes. But successful?

As world leaders gather in June for the 20-year anniversary of the landmark Rio summit, Ban is warning that climate change is at the point of no return. His report states the ozone layer is decades from recovering to pre-1980 levels. World poverty, which stood at 46 per cent in 1990, still affects 27 per cent of the population. During the same period, GDP has increased by 75 per cent, indicating a widening gap between rich and poor.

Almost one billion people have no access to clean water, while 2.6 billion have no sanitation and 1.3 billion go without electricity. More than two-thirds of primary and secondary school-age children have no education and nearly 800 million adults, most of them women, have basic literacy problems. Expect intense discussion at Rio+20 of the triple crises around food, energy and fresh water supply. The OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050 projects that, without new policies, global energy demand will increase by 80 per cent, with 8.5 out of every 10 units of supply coming from fossil fuels.

Agriculture accounts for 70 per cent of annual world water consumption – one litre of water is required for each calorie of food produced – and energy prices make fertilizers increasingly unaffordable in developing countries. Continued environmental degradation and erosion of natural capital will ultimately reverse 200 years of progress, with 40 per cent of people globally expected to suffer severe water stress, stated the OECD.

So what went wrong?

Rio 1992 framed sustainable development as three converging circles of environment, economy and society, becoming the three-legged stool at the Johannesburg Earth Summit a decade later. Too much emphasis on one leg unbalanced the stool.

An “irresponsible generation” failed to deliver a sustainable world after Rio, said Felix Dodds, executive director of the Stakeholder Forum, a non-governmental organization. Increasingly unsustainable consumption patterns, now being exported to developing countries, led to “two lost decades,” he said. Where the imbalance between economy, social justice and environment could be seen as a crisis of capitalism or globalization, Ban told KPMG’s summit that he saw “a crisis of leadership – a lack of imagination in looking at old problems with fresh eyes – and a lack of urgency as the clock ticks down.”

For Martin, the challenge at Rio+20 will be to convince those clinging to the economic leg of the sustainability stool that transforming our “brown” economy into a green growth alternative is the only way forward. “Environment is an economic issue and the costs of climate change will be horrendous,” said Martin, who expects Mexico President Felipe Calderon to push world leaders on the issue when he hosts the G20 Summit in Los Cabos on June 18, just days before the Rio+20 conference.

The message is that Adam Smith’s capitalism is out of date and the economy must create value beyond narrow concepts of growth. One major hurdle is that sustainable development has not historically been integrated into the political process. Politics and institutions of the day reward the short term, and there are few incentives to think otherwise. Political challenges are immediate, while the dividends that come with good policy require patience.

In essence, what’s needed is a political process that can bridge short- and long-term considerations. It must embrace sustainable development and be guided by science such that we can map the planet’s boundaries, thresholds and tipping points.

Will Rio+20 deliver? Levels of ambition and expectation run the gamut. A presidential election year prevents the United States from agreeing to anything more binding than broad-based principles and voluntary commitments. It is certain to avoid agendas that force obligations on other countries. On governance, the U.S. also rejects the idea of creating any overarching “world environment agency” and prefers common goals to replace dichotomous language like “North-South.” Green growth remains an opportunity to explore, but not a priority. To its north, Canada’s ephemeral ambitions refer to green patents and technology. Neither the U.S. nor Canada talks timeframes, nor do they have clear sustainable development goals.

The European Union, on the other hand, recognizes the world as very different from 1992. For it, real actions are needed in June, not after. “We want to be proactive and get things done,” said Falkenberg. “In Rio (1992) the emphasis was on developed countries and their responsibilities. The world has moved on and we need to collectively move forward.”

In that spirit, India and China must also embrace green growth, said Falkenberg. “We can’t have Canada pushing oil sands as its agenda item, or China wanting coal-fired power. Co-ordinated actions are required.” He said targets related to clean air, emissions, fish stocks, fresh water and green energy will be crucial if we are to move beyond the aspirational.

Dominic Waughray, the World Economic Forum’s senior director and head of environmental initiatives, echoed that view. “Developing countries mustn’t see green growth as a restraint on (economic) growth,” he told Corporate Knights, adding that for Rio+20 to work “real timeframes and goals are required.” It must be more than just a photo op.

The key to moving forward in a meaningful way may rest with markets, and the creation of new and better market signals. Georg Kell, head of the 1,400-member private sector organization UN Global Compact, said markets must urgently assimilate companies’ non-financial performances and translate them into market signals. Governments must place ‘’a premium on good performance, and incentives must transcend short-term thinking,” said Kell.

Vast scope exists for ecological fiscal reform, including corporate tax reductions for achieving greenhouse-gas emissions targets and tax-free dividends for investors when companies achieve environmental and corporate social responsibility (CSR) targets. As Kell told KPMG’s summit: “There is competitive advantage in CSR.”

And what if government leaders fail to deliver a brave green world at Rio+20, the same world promised two decades ago at the original Rio summit? Is failure an option? Michael Dorsey, a member of former U.S. president Bill Clinton’s Council on Sustainable Development, put it this way: “People will just have to roll up their sleeves and really fight.”