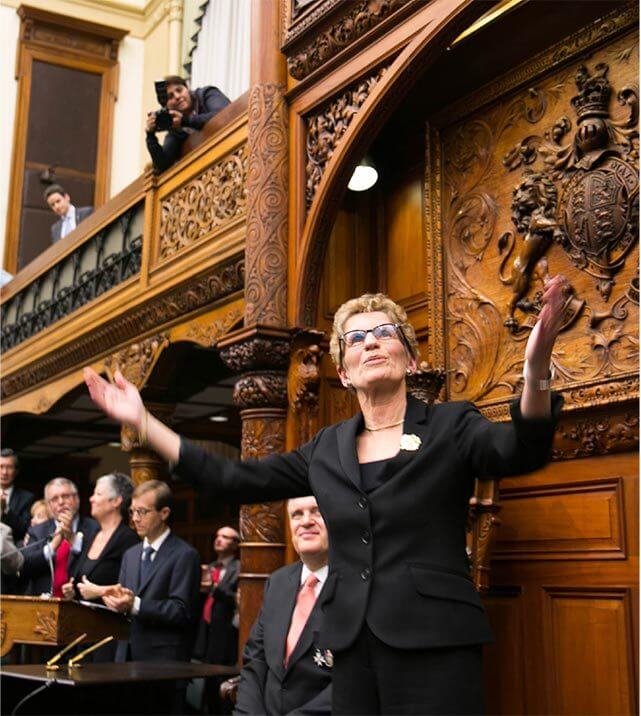

Kathleen Wynne has been Ontario’s leader since February 2013, but it wasn’t until last summer that the province’s first female premier could truly carve her own path.

Tied down with a minority government, and saddled with the political baggage of predecessor Dalton McGuinty, the affable Torontonian surprised many in a June election that, when the votes were counted, gave Wynne’s Liberal government a healthy majority. It also gave her a mandate to stay the course with what many pundits described as an activist agenda.

Six months into her second term, Wynne has arguably been most active on an issue that wasn’t a major theme in her campaign platform: climate change.

Word is, earlier meetings with Al Gore and Hillary Clinton helped motivate her to make it a priority. Wasting little time, Wynne’s first action – less than two weeks after voting day – was to add “climate change” to the official name of the province’s environment ministry.

Just as important was that seasoned cabinet minister Glen Murray, a vocal advocate for climate action, was appointed to lead the newly branded ministry. Murray was also charged with developing a plan to reach Ontario’s 2020 greenhouse-gas emissions target (15 per cent below 1990 levels), as well as crafting a long-term climate change strategy to guide the country’s largest province into 2050.

Toward that goal, Wynne has directed Murray to work with other ministers, both within and outside Ontario, through what she described in an interview with Corporate Knights as an “all-of-government” approach to meeting emissions targets.

“I think it’s pretty irrefutable now that we better get our act together and move as quickly as we can, and Glen Murray certainly feels this way as well,” said Wynne, who has called climate change the biggest under-addressed policy issue in Canada.

Indeed, she made clear that Ontario and some other provinces are tired of waiting for the federal government to act, beyond disingenuously taking credit for the efforts of others – such as Ontario’s phasing out of coal-fired power. “Even if Stephen Harper doesn’t want to have the active discussion, all the premiers in this country are having it, so de facto he’s part of it,” she said.

Leading in Lima

Ontario’s presence at the Lima climate summit in December demonstrated Wynne’s eagerness to move where Ottawa won’t.

Murray was her man on the ground – and he dressed for the occasion, wearing a colourful, nature-inspired bowtie as he issued a joint statement with his counterparts from British Columbia and Quebec. Together, the three provinces represent nearly three-quarters of Canada’s population.

Their statement, which included California’s voice, seemed a veiled shot at a federal government dragging its feet on climate action.

“Jurisdictions that choose not to lead and collaborate with other regions will find themselves missing out on new opportunities to create jobs, improve productivity and create a new low-carbon economy,” they stated, building on a similar memorandum signed by Ontario and Quebec in November. In that previous agreement, the two provinces said they would collaborate on emission-reduction measures, from carbon pricing to increased sharing of clean energy resources like hydroelectric power.

Unexpected in Lima was Murray’s announcement that Ontario will host a “Climate Summit of the Americas” in July, timed to coincide with the Pan American Economic Summit and the start of the Pan-Am Games, both taking place in Toronto. One of the goals of the July climate summit will be to strengthen a “pan-American coalition of subnational governments” in advance of December’s COP21 gathering in Paris.

In other words, who needs the feds?

In a chat with Corporate Knights shortly after returning from Lima, Murray said he has “grave concerns” about the lack of urgency shown by the federal government. “We’re realizing just how much little time we have,” he said.

In response, subnational governments are stepping in to put the brakes on GHG emissions and shift direction to a low-carbon economy, he added. “We have a decade, not a century, to turn this all around.”

As part of that subnational movement, Ontario is getting noticed. Philip Gass, a senior researcher at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, said the impression outside of Canada is that strong climate policy is expected to emerge from the province over the coming months.

“We talk to other governments, people in the private sector and the environmental community, and they definitely see Ontario as having positive movement and messaging,” said Gass, adding that Wynne isn’t wasting time capitalizing on her majority.

Asked when the federal government will step up, Gass suggested provincial policy is what matters most. “Canada’s national commitment is going to be based on provincial policy.”

It’s not that Ontario has been idle up to this point. About 7,500 megawatts of generating capacity in the province in 2003 came from burning coal. It took a few years longer than originally promised, but Ontario became coal-free last April. That milestone has been described as the single-largest greenhouse-gas reduction initiative in North America, and it represents a lion’s share of emission reductions in Canada’s electricity sector over the last several years.

Next to Quebec, Ontario has the second-lowest emissions intensity score of all provinces, according to its 2014 emissions report. At the time of publishing, the province was on track to surpass its 2014 emissions target.

Ontario’s landmark Green Energy and Green Economy Act, as well as the feed-in-tariff program it empowered, brought a flood of renewable energy projects across its borders. That – along with natural gas and energy conservation – helped its efforts to wean off coal. The economic downturn, and the shrinking of the province’s industrial base, also played a major role.

Wynne is proud of those accomplishments, but she knows it’s nowhere near enough. Transportation is now the biggest emissions beast, and it needs to be tamed. In 1990, planes, trains, automobiles and trucks were the second-highest source of GHGs and represented about a quarter of the province’s emissions. Today, it’s the highest source and accounts for a third of Ontario’s carbon footprint.

Based on current policies and trends, the province is only expected to reach 69 per cent of its 2020 target. “We’re obviously not there,” Wynne told Corporate Knights. “We still have lots to do.”

Embracing innovation

Investing in climate-friendly transportation infrastructure will no doubt be part of the solution, and on that front, Wynne’s support of Canada’s first green bond issuance demonstrated her willingness to test new approaches.

In October, the province revealed that its $500-million green bond offering was nearly five times oversubscribed. Investors from the United States, Europe, Asia, and Canada couldn’t get enough – a sign that green bonds may be a permanent fixture in Ontario’s future. The money will be used to expand transit infrastructure in the Toronto and Hamilton areas.

“What is wonderful about the green bond idea is that it makes the link between building infrastructure and people making investments in a greener, more sustainable society,” said Wynne. “We need to do more of that.”

It’s her openness to trying new approaches and embracing innovation that’s earning her kudos in some corners. Tom Rand, a clean technology investor and author, recalled when Wynne attended an energy innovation conference in Toronto. “She was there the whole day. Right to the very end,” he said, noting that most high-ranking politicians don’t tend to hang around. “To me, it showed she has real interest in the area.”

Ron Dizy, managing director of the Advanced Energy Centre at the Mars Discovery District in Toronto, said her belief in the power of innovation – both to solve climate and energy problems, but also to boost economic prosperity – tells a lot about where she hopes to take the province. “Personal commitment matters,” he said.

Commitment can only go so far, of course. Wynne’s time in the Liberal government, both as a leader and cabinet minister, has been marred by headline-grabbing controversies that typically involve the mismanagement of millions, sometimes billions of dollars.

Opposition politicians never hesitate to paint the Liberal government as reckless and expensive with taxpayer money. That voters handed Wynne a majority government last June suggests they were putting their trust in her, not necessarily the party.

In Rand’s review, her biggest challenge will be to establish a compelling link between climate action and economic growth, and look more holistically at how to achieve both. It will also be important for her government to avoid regularly interfering with and changing policy direction after programs have been created and rules have been set, beyond minor tinkering.

“The Green Energy Act has pissed off a lot of people,” said Rand, referring to the Liberal government’s tendency to meddle, sometimes significantly, with the details of programs that were supposed to provide market certainty and predictability for investors and electricity consumers. “They need to find a follow-up play that’s more politically sophisticated.”

We’ll likely know just how far Wynne is prepared to go on climate action when Ontario hosts its climate conference in July. It will present a good opportunity for Murray to unveil the province’s short-term emissions plan and long-term climate strategy, as well as details on how – not if – the province will price carbon.

“Carbon pricing is going to be part of it,” said Murray, explaining how the economic downturn derailed previous attempts at a cap-and-trade program that stretch back to 2007. With the economy making a recovery and jurisdictions like British Columbia proving that carbon pricing works, cap-and-trade – or possibly a carbon tax – is back on track in Ontario.

“When you see it, it will be real, it will be efficient, and it will be economically positive,” he assured