Two people are interviewing for a job. One is bright, qualified and Black; the other, less impressive, but white. The hiring manager, who has a history of racism, places the Black applicant’s resumé in the “reject” pile.

Until recently, that’s how many may have imagined anti-Black racism in business: isolated acts of discrimination performed by a prejudiced few. But the death of George Floyd – an unarmed 46-year-old Black man killed by a Minneapolis police officer onMay 25 – and the widespread protests that have erupted globally in response are forcing Canada’s business community to rethink racism.

In the weeks since Floyd’s death, businesses around the world have been scrambling to make diversity pledges. On June 8, the Financial Times reported that major corporations had recently donated more than $450 million to American civil rights groups. Last month, the Business Council of Canada had over 130 CEOs sign a statement denouncing all forms of racism. But anti-racism advocates say corporations will need to go beyond words and donations, particularly since research reveals that systemic racism in offices and executive suites isn’t a deviation from the norm – it is the norm.

A study to be released next month by Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute analyzed the diversity of companies in Vancouver, Montreal, Calgary and Toronto in 2019. Of 1,639 board members from 178 corporations, they found only 13 Black board members (0.79%), while white members held 1,483 spots (91%), and other racialized members held 61 spots (the institute was unable to classify some members). To put that in context, almost a tenth of Toronto is Black, while Black people make up 3.5% of Canada’s population, according to the most recent census.

Corporate Knights did its own count. After analyzing S&P/TSX 60 companies, we found that only six of the 799 senior executives and only four of the 686 board members at all 60 companies were Black. That’s less than 1%.

How Canadian companies are responding

Corporate Knights reached out to S&P/TSX 60 companies for comment. Of the 60 firms, the only companies that had Black leaders in their boardrooms or showcased on their websites’ leadership pages at the executive level were CIBC, CP Rail, Brookfield Asset Management, CGI Inc., TD Bank, Emera Inc. and Enbridge. (Corporate Knights restricted its executive count to those featured on companies’ leadership webpages. For example, two of Gildan’s VPs are Black but were excluded from our count because of this criteria.)

Of the companies that had no Black representation at the board or executive level, Restaurant Brands International (RBI) – which owns such companies as Tim Hortons and Burger King – acknowledged that change was needed. “We absolutely agree that we need more gender and racial diversity within our board and leadership teams,” said an RBI representative. To ensure there is “a permanent diversity shift that permeates our culture,”this week RBI’s CEO, José Cil, committed to ensuring that at least 50% of final-round candidates interviewing for roles at RBI offices will be from “demonstrably diverse backgrounds, including race.”

Suncor says it’s reviewing its inclusion and diversity strategy, which currently focuses on women, Indigenous peoples and the LGBT+ community, to ensure a more active involvement of Black and racialized communities.

A number of companies said that they have established diversity and inclusion (DC&I) councils, including Canadian Tire, Bell, BMO, Bausch Health, Agnico Eagle, Telus and Magna International. Magna stated that its DC&I council is “aligning with our talent review process to ensure we have broader visibility and opportunity to increase our diversity in leadership roles.”

Some corporations also highlighted their financial support for the cause: BMO donated $1 million to a number of social and racial justice groups while Canadian Tire donated $800,000 to various Black organizations. Canopy Growth noted it has been a longtime supporter of Cage-Free Cannabis (which provides legal services to communities of colour that have been disproportionately harmed by the war on drugs).

Canopy Growth says it’s also “rolling out a number of D&I [diversity and inclusion] initiatives, including benchmarking diversity and publicly reporting on our progress.”

Fortis Inc. said that while there are no Black executives in its holding company, several of its subsidiaries have Black executives and directors. Notably, FortisTCI recently appointed Ruth Forbes, a Black woman and current VP of corporate services, as its incoming president and CEO.

Teck Resources said that it considers diversity in the selection criteria for new board members and senior management team appointments and that “4 out of 12, or 33%, of directors on Teck’s board are visible minorities.”

Telus and Loblaw have both stated that 18% of their executives identify as “visible minorities”. Like most companies%, Loblaw acknowledged that it didn’t “break those numbers down further.”

Telus, which has been named one of the Best Diversity Employers in Canada by Mediacorp nearly a dozen times, told Corporate Knights, “We are committed to increasing the presence of underrepresented groups across key areas of our organization, including our Board.” Telus shared no specific targets.

Push for concrete corporate commitments

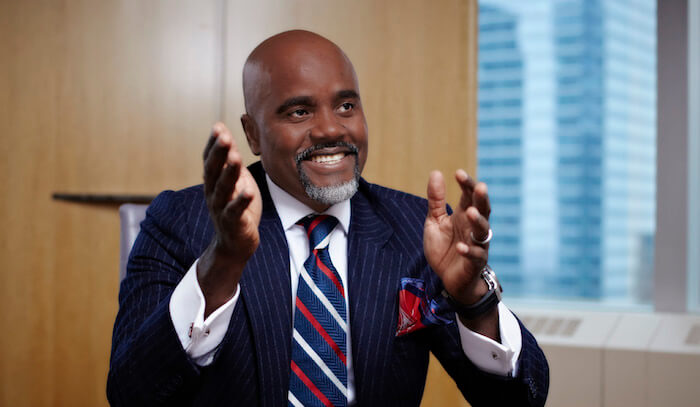

Wes Hall, executive chairman of Kingsdale Advisors, finds Corporate Knights’ TSX 60 data unsurprising. “We live those numbers every day,” he says. “We’re not shocked by them.”

Though Hall says he has seen companies increase diversity when they set their minds to it, drawing a parallel to the recent corporate push for gender diversity at the board level. “All of a sudden last year, every single company on the TSX 60 has a woman on their board, right? Because they put their mind to it. But where were the women before? They were stuck in middle management, they were stuck at that glass ceiling, looking up.”

On June 10, Hall formed the Canadian Council of Business Leaders Against Anti-Black Systemic Racism. The council’s membership is a who’s who of Canadian business, including CIBC CEO Victor Dodig, Cisco Canada president and CEO Rola Dagher, and Fairfax Financial Holdings CEO and chair Prem Watsa. It aims to ensure that businesses deliver on promises they’ve made to fight systemic racism and support the Black community.

The council’s BlackNorth Initiative, which will hold a summit on July 20, is urging CEOs to sign a pledge to remove systemic anti-Black barriers. Commitments include earmarking 3% of corporate donations and sponsorships to create economic opportunities in the Black community, ensuring that at least 3.5% of executives and board roles based in Canada are held by Black leaders, and hiring at least 5% of our student workforce from the Black community, all by 2025.

“We need to be uncomfortable and embrace the challenge to grow,” says BlackNorth Initiative co-chair Dagher. “It is absolutely time for us to stand up . . . A statement without a commitment is not anything at all.”

Broadening the recruitment pool

While businesses are being called out for fumbling on diversity, public boards are making progress. Ryerson’s Diversity Institute says government-appointed boards – like those on publicly owned energy utilities, public transportation agencies and cultural institutions – boasted 63 Black board members out of a total 2,684 (2.35%). While the percentage is still small, it’s almost three times that of corporate boards.

That jump in diversity could be key to colour-correcting corporate Canada. Wendy Cukier, director of the Diversity Institute, says corporations often overlook talent found in public boards. She noted that non-profit boards often recruit candidates with corporate experience – but it’s not a two-way street. “There are lots of racialized people – and specifically Black people – who are lawyers, accountants and IT specialists that represent community organizations and could make significant contributions to corporate boards,” she says.

A study by Stacey R. Fitzsimmons, associate professor of international management at the University of Victoria, observed how often hiring happened through informal networks: 73% of Canadian board members reported that the most common method used to recruit board members involved recommendations by existing directors. Cukier says informal networks like these consist mainly of people with similar backgrounds, thus excluding qualified, diverse candidates.

“People tend to associate with people just like them, who belong to the same golf clubs,” says Cukier. Case in point: a 2014 study published by the Public Religion Research Institute, which found that 75% of white people in the U.S. have completely Caucasian social networks.

Some companies are now vowing to address this bias by changing how they hire. RBI reps say the company has “updated our search criteria for all senior positions to urge our recruiters to increase the diversity of candidates being forwarded,” adding that a steering committee of senior leaders is heading up its diversity and inclusion efforts.

Cukier says moves like this encourage budding Black leaders to envision themselves in leadership roles, which affects their aspirations and their access to mentorship.

The rewards of cultivating diverse leadership are well documented: a study by the management consultant firm McKinsey found that companies with more gender- or racially diverse executives were 33% more likely to have above-average profits. Those with diverse boards were 43% more likely to see above-average profits. Inclusively staffed companies enjoy broader talent pools, the ability to respond to a diverse set of markets, and reduced legal and reputational risk, researchers say.

But even when Black Canadians break into the boardroom, they still brave racism both overt and covert. Scarborough-Guildwood MPP Mitzie Hunter described how, after giving a speech for the Toronto-based technology incubator she was then the CEO of, a man told her she was the most “articulate Black person” he had ever heard.

“I’m pretty sure he thought he was giving me the highest compliment,” says Hunter. “Right in that moment, I stopped being the CEO . . . on a big stage representing my organization, and I became almost a little girl because of his words.”

Hunter says such comments can leave Black people feeling undermined and exhausted.

“That’s a waste,” says Hunter. “Your energy and your creativity and your talent and your thoughts and your ideas should be going into solving challenging problems that you’re there to do, rather than guarding yourself against this type of aggression.”

It’s also a wasted opportunity to reduce risk and group-think, says Cisco Canada’s Dagher, who fled Lebanon as a child.“You don’t want to hire people that look like you, that speak like you, that think like you; you want to hire people that can challenge you,” she says.

Regulating diversity

Some diversity advocates question whether the recent corporate pledges can translate into real change. Canadian Senator Ratna Omidvar says that, while the recent response from corporations is encouraging, lasting change comes from regulation.

“What we have to rely on, then, is the law. It is the law that changes behaviours,” she says.

When it comes to long-standing efforts to improve gender diversity on boards, Senator Omidvar’s statement is largely backed up by empirical evidence, which shows that the countries that have made meaningful progress in increasing the number of women on boards all have legal targets or quotas driving that progress.

Canada’s legal system has only recently begun supporting corporate diversity. Introduced by Navdeep Bains, Minister of Innovation, Science and Economic Development, Bill C-25 makes companies disclose or explain why they’re not creating plans to increase the number of women, racialized people, persons with disabilities and Indigenous citizens they hire in senior management and board positions. As of January 1, 2020, this applies to federally incorporated companies such as airlines and banks.

A growing number of companies, including Calgary-headquartered Cenovus Energy, now have formal board diversity targets. Cenovus says it has “an aspirational target to have at least 40% of independent directors be represented by women, Aboriginal peoples, persons with disabilities and members of visible minorities.”

Omidvar hoped that Bill C-25 would make such targets mandatory, but her amendment to the bill making this so was not approved by Parliament.

“I’d describe the government’s legislation as a tap on the shoulder of business to do the right thing, whereas I would have preferred a nudge,” Omidvar says.