This story was originally published by Floodlight and Mountain State Spotlight

For Pleasants County native Rick Miller, landing a job at Pleasants Power Station after several years as an industrial contractor was a pivotal moment. It tripled his income, didn’t require him to travel and allowed him to cut down on the gruelling hours he was previously working. “It was a very good job,” Miller says. “It changed my life, actually.”

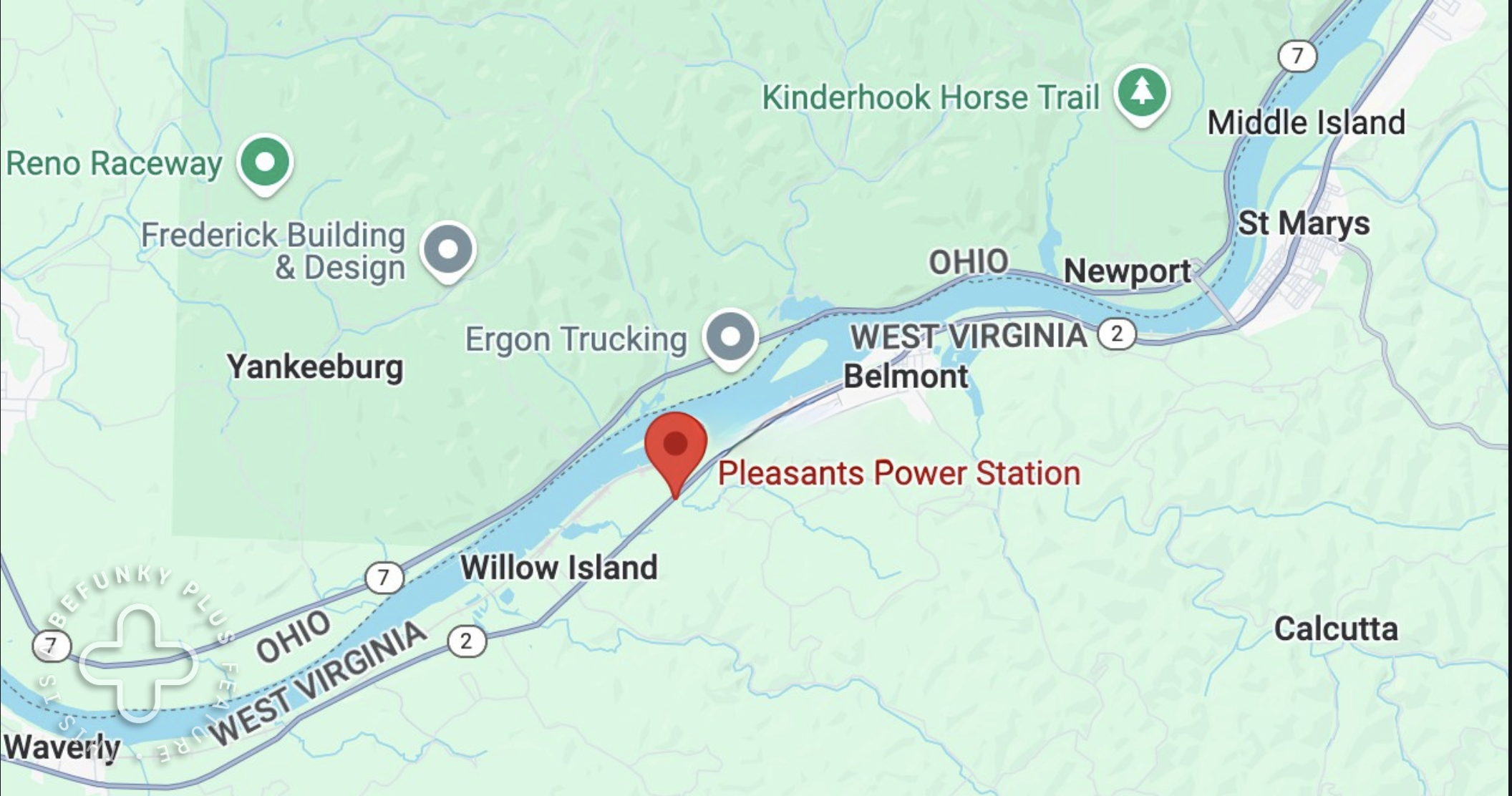

For decades, the imposing facility in Willow Island, West Virginia, alongside state Route 2 served as an economic powerhouse for the county, employing hundreds of workers from communities up and down the Ohio River Valley and providing millions in revenue to the county.

But a few years ago, much like other coal-fired power plants across the country, Pleasants’ future was looking increasingly unstable. Ownership of the plant had changed several times, and there was a bankruptcy. After a tumultuous few years, Miller decided to retire in 2021 after 20 years at the plant – slightly earlier than he originally planned. The uncertainty of the plant’s future was one of the reasons he left. “They were saying they were going to close, and then they were going to stay open,” he says. “It was taking its toll on me mentally.”

As local and state officials scrambled to prevent Pleasants being shut down for good, Omnis Energy, a company relatively new to West Virginia, pitched them on a new chapter for the power station. The company’s plan promised “revolutionary” technology that would still make use of coal, produce a high-value mineral and generate greener electricity, as well as create new jobs and prevent the destruction of a plant that has been an essential part of this community for decades.

Those promises are now backed with a $50-million, 1% loan from the state’s economic development agency. But the plant’s – and the community’s – future now rests on an unproven technology and a company juggling multiple projects in West Virginia, with a history of loan defaults by the parent company and its CEO, Simon Hodson.

Earlier this year, a former senior employee sued the company, saying she confronted Hodson in August 2023 about his “ongoing efforts to defraud government officials for investment funds,” including the state of West Virginia and the U.S. Department of Energy. A spokesperson for the company said, “Omnis categorically denies making any misrepresentations to federal or state officials.” The spokesperson also maintains that the technology has been tested and is commercially viable.

But in a small county where the local schools, services and larger economy are dependent on the facility’s jobs and tax revenue, the stakes for whether this project succeeds or fails are very high. “It would be devastating to lose those tax dollars,” says Sheri Fleegle, executive director of the Pleasants Community Foundation, adding that her organization depends on donations for its scholarships and to support local charities and institutions. “You lose those jobs, people aren’t able to make those kinds of contributions any longer,” she says. “It would be devastating for many, many things here in the community.”

The elephant in the living room

The power plant has a long history in Pleasants County, starting with its construction.

Five months into her time at the weekly St. Marys Oracle newspaper in 1978, Fleegle was handed a camera and sent down the road to cover what was thought to be an explosion at a nearby chemical plant. Instead, she found the aftermath of one of the worst construction disasters in U.S. history. A cooling tower at the Pleasants Power Plant had collapsed mid-construction; 51 workers plunged to their deaths.

Like others in the small community, Fleegle knew several workers on the tower, including a former classmate. “I don’t know that there was anyone in this community that wasn’t in some way touched by that,” she says.

On the day the cooling tower collapsed, Miller’s uncle was working the crane. Retired Pleasants County teacher Cynthia Alkire had students with family working there. And county native Allen Thacker lost three of his former high school classmates. “It’s one of those things; it’s always been the elephant in the living room,” Thacker says. “Everybody has some association with it.”

That searing tragedy, along with the plant’s deep economic and emotional ties, was one reason county officials like Pleasants County Commissioner Jay Powell fought to save the plant, which provided electricity to 13 states on the Eastern Seaboard. “We owed it, not only to the community and the state and the East Coast but to those men that sacrificed what they did,” he says.

But the plant’s struggles continued, despite Governor Jim Justice signing a $12-million tax break for then-owners FirstEnergy in 2019. FirstEnergy was suing a coal company owned by Justice at the time, claiming it reneged on a $3.1-million deal.

In December 2022, Pleasants Power Station was sold to a company that intended to shut down and eventually demolish the plant. Undeterred, West Virginia lawmakers passed measures in 2023 requiring the state’s approval to decommission fossil-fuel power plants and strongly encouraging utility companies to buy Pleasants. At the time, the power plant employed more than 150 people and contributed $1.75 million in taxes to support the county and local schools.

Worry about the plant reverberated throughout the community, even prompting an employee-driven effort to prevent the facility from closing. Says Powell: “There were literally community prayer vigils.”

So when word got out that Omnis wanted to keep the plant open – and promised to expand its workforce – it felt miraculous. “We recognize it’s something that could falter and this plant may not be there at some point, but right now, we believe it’s open because we experienced a miracle,” Powell says. “Not only to be open, but maybe for it to do something that no other plant’s done in the world. Only God can get credit for that.”

‘This state understands coal’

Late last summer, Governor Justice told attendees at the annual meeting of the West Virginia Chamber of Commerce that he was about to share something “un-flat-believable.” They were gathered at the Greenbrier Resort, which the governor owns.

Justice, a coal magnate whose own coal company has fallen on hard times, said a power plant was taking on “new life.” Projected on the screen behind him was Powell, standing near a cooling tower with steam rising into the sky. Powell told the crowd he had tears in his eyes that morning as he drove down Route 2 to the Pleasants Power Station. The coal plant had restarted.

Until that day, Pleasants had been mothballed for several months. While the power station was now back on, its new owners, Omnis Energy, had much bigger plans. “There’s no other company in the world that’s planning to do something like this,” Hodson, CEO of parent company Omnis Global Technologies, told the West Virginia Public Energy Authority during a presentation in September 2023.

Omnis’s plan was to keep the plant running as-is for two years while his company built new “quantum reformers” to produce hydrogen and graphite from coal. Omnis then would convert the existing plant to burn hydrogen, emissions-free.

Eventually, Pleasants would produce millions of tons of graphite a year and more than enough hydrogen to power electricity generation at the plant’s full capacity, keeping the power flowing across West Virginia, the mid-Atlantic and parts of the Midwest.

The company would sell the graphite – a mineral used in a variety of products, including electric vehicle batteries – and any extra hydrogen. And to do it, Omnis planned to use a lot of coal – not burning it, but in Hodson’s words “ripping it apart” – using a process called pyrolysis.

Hodson said the plant anticipated buying eight to 10 million tons of coal a year to convert into hydrogen and graphite, about two to three times more than the power plant regularly uses. A recent presentation by the company indicates it now intends to use a mix of coal and methane, as Omnis was “encouraged to use a blend of hydrocarbons at this particular plant,” a representative said.

Originally based in California, Omnis Global and its subsidiaries have taken to West Virginia quickly. In the span of a year and a half, Omnis has announced plans for a $60-million project to extract rare-earth elements from coal waste in Wyoming County and a building-material construction factory in Bluefield, both in West Virginia, as well as the Pleasants project. Justice, who appeared at every announcement, declined to comment for this story.

“I’m a newcomer; I don’t speak the language of West Virginia yet,” Hodson said last September, adding that he chose the Mountain State for his expansion plans because “this state understands coal.”

A new way to produce graphite, but questions remain

Omnis’s plan for the Pleasants plant arguably hits all the notes for West Virginia officials: a reliable use of the state’s coal in perpetuity, a way for West Virginia to diversify its energy production and a feel-good story about saving and repurposing a power plant deeply embedded in its community.

But there’s a dearth of public information about how the technology actually works and its level of success in producing hydrogen or graphite. Paul Rodden, a hydrogen consultant, said of the Omnis proposal in a June 2023 episode of The Hydrogen Podcast, “It’s worth speculation as to why we haven’t heard of any trial or demo applications before this.”

Omnis says its process subjects coal and gas to extremely high temperatures in the absence of oxygen – nearly half the temperature of the surface of the sun – breaking it down into hydrogen and graphite through pyrolysis.

While pyrolysis is very common – it’s the same process that makes charcoal – doing so at such temperatures for so long is likely to contribute to extreme wear and tear of equipment and impurities in the graphite, says Nicole Labbe, a chemical engineer and associate professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder. “There’s not a lot of materials that can withstand 2,000-degree-Celsius temperatures over long periods of time,” she says. “Could this be sustained, or is this going to be a frequently shut down, replaced-parts type of situation?”

Labbe, who regularly reviews technology proposals submitted to federal government agencies, says that Omnis’s publicly available information is intriguing but that it lacks key data to fully assess its technology, with “wildly optimistic” projections of hydrogen and graphite production.

“There’s a lot of big unknowns,” she says.

She points to a different company, spun out of research at Rice University, that produces graphene – an incredibly strong carbon material that can be produced from graphite – using high-temperature pyrolysis. Unlike Omnis, that company has published data on the results.

Representatives for the company say that “Omnis is unaware of any experts that have reviewed their technology that are skeptical.” In a statement, they said a commercial version of the reformers has been operating for more than seven years at the Pennsylvania waste coal plant that Omnis now owns. But that facility burned down in May. The state fire marshal was unable to determine a cause except to say that it was not suspicious. Representatives for Omnis said the subsidiary intends to rebuild that plant.

And while the company unveiled a pilot project at the West Virginia site in September, many questions remain – including questions about the technology.

During a tour at the Pleasants Power Plant of the pilot project on September 9, Omnis Energy president Rich Hulme told WTAP that the company had been running tests for six weeks, in part to find “the balance between cooling and heating source to make sure the device itself doesn’t melt.” When asked about the progress in producing graphite, Hulme said, “The graphite is still being produced. We’re still developing that particular part of the process.”

In a recent presentation, Omnis said that at full capacity the plant would produce three million tons of graphite a year – down from six million in Hodson’s earlier estimation – because the company no longer plans to exclusively use coal.

Still, the total current worldwide demand for both mined and synthetic graphite is just 3.8 million tons. Demand is expected to grow alongside electric vehicles and semiconductors; a recent projection suggests a total global market of just over seven million tons a year by 2035.

If those projections and Omnis’s are both correct, the company would supply the vast majority of all the graphite used in the world.

Hulme also told the Parkersburg-based TV station that the company will produce hydrogen at a cost of $100 a ton compared to an industry goal of $2,000 — “one-20th the cost of what the rest of the industry is trying to achieve in their production of hydrogen.”

Hodson, Omnis targeted in lawsuits

There are other reasons to be skeptical of Omnis’s promises to Pleasants County.

The same day Justice was celebrating the new start for Pleasants at the Greenbrier Resort, Omnis’s vice president of government relations confronted Hodson there, accusing him of lying to government officials.

In a federal lawsuit filed in Pennsylvania, Michelle Christian, who joined Omnis as vice president of government relations in 2020, said she began questioning Hodson about his various companies because “certain things did not make sense financially.” Christian also alleged she was subjected to gender and religious discrimination by Hodson and other executives who are members of the Mormon Church.

In what was described in the suit as an hours-long conversation, Christian said she told Hodson “she would not lie on his behalf.” Less than two weeks later, she was out at the company. (The two sides dispute whether she quit or was fired.) Christian, whose case is ongoing, declined to comment.

Omnis described Christian’s accusations as “unfounded and defamatory” and noted that the company is pursuing a separate case against her over a disputed laptop. In her lawsuit, Christian said it is her personal computer, not company property.

Over the past seven years, Hodson and an Omnis subsidiary also have been sued for nonpayment of loans.

In 2017, Hendricks Resources Limited sued Omnis Mineral Technologies after it defaulted on two loans signed by Hodson worth $3 million.

The second lawsuit was filed by Shannon Sorensen in Santa Barbara, California. Court documents say she loaned Hodson about $3 million between 2012 and 2015. By 2021, with interest, Hodson owed Sorensen just under $5 million, the complaint said. When he failed to pay, Sorensen sued.

During settlement discussions in 2022, Hodson’s lawyers said he was on the verge of closing on $500 million in investments for “a venture in West Virginia” and would soon pay Sorensen back, according to documents filed by her lawyers. Several months later, Sorensen’s legal team discovered that Hodson had made a nearly half-million-dollar loan to the re-election campaign of Republican Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton during the same time he failed to pay the initial settlement.

Both lawsuits were settled for undisclosed amounts. A written statement from a spokesperson for Omnis described Sorensen as a “long-term, close family friend to the Hodsons” and said the case was “fully settled to Mrs. Sorensen’s satisfaction” and paid by Hodson with personal funds. In regards to the Paxton loan, Hodson was “happy to provide temporary assistance,” and the loan was paid back in full. Lawyers for Sorensen declined to comment.

A state loan stamp of approval

If West Virginia officials knew any of this, it did not prevent them from loaning Omnis $50 million for the Pleasants project. The West Virginia Economic Development Authority Board approved the loan in November 2023 during a special session, outside of its regular monthly meeting.

The state agreed to lend Omnis the money, with the company matching the $50-million investment, to buy land adjacent to the current plant, build the first demonstration facility for graphite and hydrogen production, and upgrade infrastructure to ship coal in and graphite out, according to records obtained under a public records request.

The agreement also said the company would pursue an $800-million loan from the Department of Energy for clean energy projects. The Wall Street Journal reported in July that the company was not invited to apply to that program because it lacked enough demonstration hours of the technology. Representatives for Omnis said, “The technology has been tested and proven. The DOE just requires additional operation hours to meet their funding criteria.”

Powell and the local St. Marys Oracle newspaper reported that DOE officials had visited the site in August, but requests to DOE to verify that visit were not returned.

How did the WVEDA board decide Omnis was a good investment? Requests for comment to the board’s chair and vice chair about how much the state investigated Omnis and its technology were referred to the office of executive director Kris Warner. A public records request to WVEDA for additional documentation and correspondence related to the loan was largely denied. In a phone interview, Warner did not answer questions about the level of scrutiny the agency applied to Omnis.

But Omnis was clearly well-known to state officials. Warner mentioned in a public presentation in September 2023 that he enjoyed seeing the Omnis office “out in Santa Barbara.” Warner told Floodlight and Mountain State Spotlight he had stopped by the office as a private citizen to see its construction materials technology while visiting family in California.

Weeks after the Omnis state loan was finalized, Warner filed to run for West Virginia secretary of state. Conservative Policy Action, a super PAC funded in part by contributions from a top Omnis investor and its chief financial officer, spent nearly two-thirds of its money – more than $218,000 – to support Warner or oppose other candidates, according to Federal Election Commission data.

In July, the super PAC’s chairman, Mark Scott, resigned his position as West Virginia’s administration secretary following concerns about potential conflicts of interest with his government position. That funding is now the subject of an election complaint filed by one of Warner’s primary opponents, Ken Reed.

Warner rejected any suggestion of conflict of interest, telling Floodlight and Mountain State Spotlight that loan decisions are made by the WVEDA board or the governor. “I don’t approve loans,” he said.

Uncertain future for Omnis businesses in West Virginia

Meanwhile, Omnis’s other projects in West Virginia are running behind schedule.

Construction on the building-material construction factory is underway in Bluefield, but Jonathan Hodson, the CEO of the building company and the son of Omnis CEO Simon Hodson, told a local news station that weather and supply chain issues had pushed back the opening, originally scheduled for late 2023. The company now expects to start hiring by early 2025.

In Wyoming County, very little appears to have happened in the nearly two years since the initial announcement of the coal-waste project. The Wyoming County Economic Development Agency is “actively working with [Omnis] to see if they need any assistance along the way,” says executive director Christy Laxton. She could only confirm the company hadn’t publicly announced a location, citing a nondisclosure agreement the county EDA had signed.

In Pleasants County, some skepticism around Omnis’s promises has seeped in, but many in the community remain cautiously optimistic. Omnis is required to pay back the state loan for the Pleasants project by May 2026. “I think everybody’s hopeful. And that’s what I am,” retired teacher Cynthia Alkire says. “Now, am I 100% sure that that’s going to work? No, but I don’t think anybody can be 100% sure.”

It’s possible this project will work as promised; taking risks on unproven technology is what allows us to advance, says Labbe, the chemical engineer in Colorado. But with the hopes of an entire community riding on a single project, it opens the door to “maybe not look at things as closely as you should,” Labbe says. “It doesn’t mean that that’s what’s happening here.”

Right now, there is no other plan for the power station.

If the project fails, Fleegle says, “There would be a lot of belt-tightening. Hopefully, we don’t have to address that.”

This article was originally published by Floodlight, a non-profit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action. It has been edited to conform with Corporate Knights style. WTAP reporter Chase Campbell contributed to this report. Mountain State Spotlight is a West Virginia-based non-profit newsroom producing accountability journalism from around the state.

Taylor Kate Brown is an independent journalist focused on local climate-change-action stories. Sarah Elbeshbishi is Mountain State Spotlight’s environment and energy reporter.