The federal government is committing Canada to achieving a net-zero emissions goal by 2050, but getting there will require substantially more action from provincial governments to reduce greenhouse gases.

Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson released Ottawa’s bulked-up plan in December, highlighted by a proposal to increase the federal price on carbon to $170 a tonne by 2030 from $50 a tonne in 2022. After the Supreme Court of Canada upheld the constitutionality of the federal carbon price in a March decision, the fate of the Liberals’ plan now hangs on whether they can return to power in the next election, which could come this year.

However, the plan’s success depends as well on the GHG mitigation efforts of provinces, municipalities, the corporate sector and even individual Canadians.

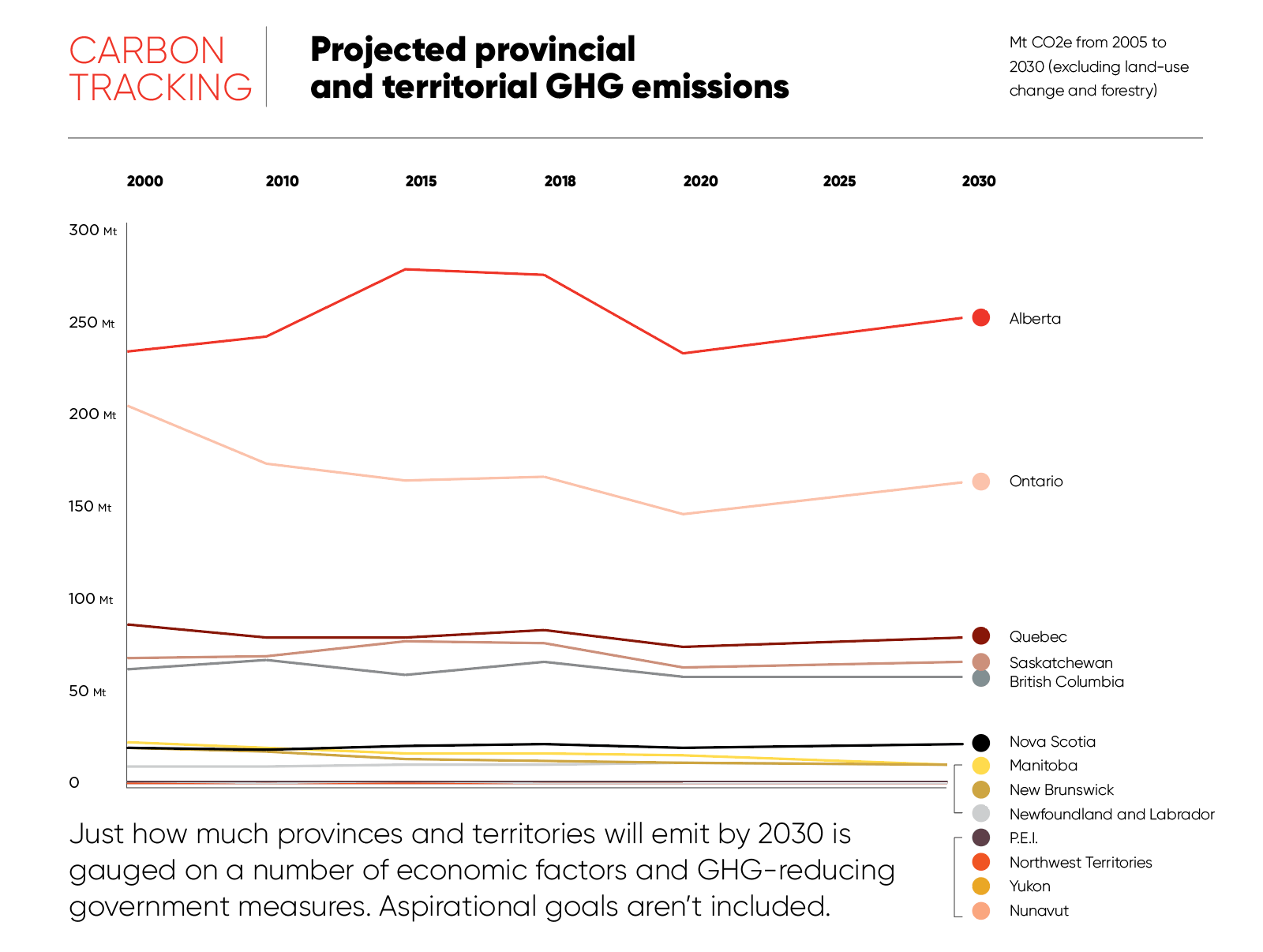

The new Liberal plan projects that the additional measures it has announced would result in Canada reducing its GHG emissions by 32% in 2030 from 2005 levels. That’s just slightly better than the 30% target the government adopted under the Paris Agreement. The United Nations has said we need global reductions of 55% by 2030 to have a reasonable chance of holding the increase in average global temperatures to 1.5°C.

With additional efforts from provinces and the private sector, the federal government said, Canada could achieve a 40% reduction from 2005 levels by 2030. The Liberal government is now working on a new 2030 target, to be announced in the run-up to the UN’s COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in November.

The target of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 is widely shared by governments and corporations around the world. Federal Conservative Party Leader Erin O’Toole has endorsed it, as have provincial governments in British Columbia, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland and Labrador. Quebec is reviewing its goal of at least an 80% reduction by 2050 and has indicated it will adopt the net-zero target.

However, three of the country’s largest provincial emitters – Alberta, Ontario and Saskatchewan – have not endorsed that long-term goal.

“There’s clearly a big role for provincial and territorial governments on the path to net-zero,” says Dale Beugin, research director for the Canadian Institute for Climate Choices, which in February released a report called Canada’s Net Zero Future. Meeting Canada’s climate goal will require “increasingly stringent, economy-wide policies such as carbon pricing in every province, complemented by provincial policies like stringent building codes and infrastructure investments,” Beugin says.

Provinces and territories also have a role in commercializing and deploying technologies like carbon-capture and green hydrogen that could play a major role in emissions-reduction strategies a decade from now.

Given that imperative, here is how the provincial governments are responding. It should be noted, however, that emissions trajectories reflect the combined efforts of federal, provincial and municipal governments, as well as publicly owned utilities and corporations.

Rubric: A letter grade was assigned to each province and territory based on the ambition of their GHG targets, the measures they’ve implemented to meet them and their overall support for climate change action.

The net-zero provincial report card was prepared with financial support from the Ivey Foundation.

Source: Based on 2018 figures from Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2019 GHG emissions figures were released at press time showing little change.

British Columbia

British Columbia is the fifth-largest emitter among the provinces and was headed in the wrong direction under the previous Liberal government. After winning a minority government with support from the Green Party in 2017, NDP Premier John Horgan committed the province to an aggressive climate agenda, which he began to implement. He won a strong majority after a fall 2020 snap election and has promised to increase B.C.’s climate efforts.

Current Emissions: 66 Mt in 2018, 5.6% higher than in 2005. Since hitting a low point in 2015, B.C.’s annual GHG emissions rose by nearly 12% – or 7 Mt annually – by 2018.

Emissions Per Capita: 13.2 tonnes

Climate Strategy: B.C. has a legislated target to reduce emissions by 40% below 2007 levels by 2030, and by 80% by 2050. During the 2020 election campaign, Horgan endorsed a net-zero target for 2050. The provincial government has tightened its clean fuel standard and building codes to ensure that all new buildings be net-zero ready by 2032 (see story on p. 53). It’s providing $6,000 rebates for EV purchasers and mandating that 30% of new vehicles sold in the province be zero-emission by 2030, and 100% ZEV by 2040.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: B.C. was the first province to introduce an economy-wide carbon tax in 2008, and studies have concluded the levy succeeded in keeping a lid on emissions as the provincial economy grew. The B.C. tax was originally designed to be revenue-neutral, with offsetting reductions in other taxes when it was adopted in 2008. That is no longer the case. The rate of the B.C. levy will rise to match any federal increase in its carbon price.

Long Shot: B.C. is proceeding with the controversial Site C dam, which is substantially over-budget and plagued with geotechnical problems. The government argues that power from Site C can be used to electrify energy-intensive natural-gas processing plants in northeastern B.C. and reduce emissions from the gas fields.

Blind Spot: The measures outlined in B.C’s 2018 climate plan will achieve only 75% of the reductions the province has committed to by 2030. Horgan had promised to outline how it would achieve the other 25% but has not yet done so. The government will have to account for rising GHGs from the natural gas fields of northeastern B.C. and from the Shell-led liquified natural gas (LNG) export facility being built in Kitimat, which will be one of Canada’s largest single sources of carbon emissions.

Projected Emissions: Based on measures in place in 2019, the federal government projects B.C. emissions will fall by 6.3% between 2005 and 2030.

Grade: B+

Alberta

After two decades of aggressive growth in oil sands production, Alberta has widened its lead as the country’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases. In 2018, its GHG emissions accounted for 37% of Canada’s total, while its population represented 11% of the national total.

Current Emissions: 273 Mt in 2018, 18% higher than 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 63.4 tonnes

Climate Strategy: Premier Jason Kenney’s United Conservative Party (UCP) government has put forward few measures that would lower Alberta’s emissions. The province has no 2030 target or long-term goal for GHG emissions.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: The UCP government has maintained the coal-power phase-out policy for the province’s power utilities that was put forward by previous federal and provincial governments. Armed with a $1.8-billion compensation plan put in place by the former NDP government, Alberta’s utilities are rapidly shedding their dependence on coal. GHGs from the province’s electricity fell from 50 Mt in 2015 to 33 Mt in 2018 and could hit 20 Mt by 2023. Kenney has replaced the NDP’s pricing system on large industrial polluters with a UCP version that will cost large emitters less than they would have paid under the NDP plan but was nonetheless approved by Ottawa.

Long Shot: The Kenney government is also working on strategies to deploy potentially game-changing “wild card” technologies identified by the Institute for Climate Choices. Provincially funded Emissions Reduction Alberta and Alberta Innovates finance the development and deployment of technology that would lower GHGs and make industry more competitive. Alberta is urging the feds to commit $30 billion over the next decade in subsidies and tax incentives for carbon-capture projects. However, there are no guarantees that carbon-capture, hydrogen, carbon fibres or geothermal energy will ever be competitive on the massive scale needed to impact Alberta’s and Canada’s emissions challenge.

Blind Spot: Since taking office in 2019, Kenney has rejected pressure for a comprehensive climate strategy, seeing it as an attack on the province’s oil industry. He has fought the federal government over consumer carbon levies, scrapped provincial energy-conservation programs, and gone to war with environmental groups over the opposition to new pipelines and oil sands expansion. Fuelled by strong growth in the oil sands, industrial emissions increased by a staggering 82% since 1990.

While leading oil sands producers have announced targets to reduce GHGs, dramatic changes in Alberta’s emissions will occur only with large-scale investment in new technology (though that won’t negate Scope 3 emissions in whichever province/country consumes that oil in a combustion scenario). Weak crude prices, limits to market access and an increasing climate focus among investors will make it tough for companies to attract the capital needed to deploy that technology. The press secretary for Alberta Environment Minister Jason Nixon did not respond to several requests for comment.

Projected Emissions: In the biennial report submitted to the UN last year, the federal government projected Alberta’s emissions would grow by nearly 12% between 2005 and 2030.

Grade: D-

Saskatchewan

With its small population and heavy economic reliance on coal and oil, Saskatchewan has the highest GHG emissions per capita among Canadian provinces and is the fourth-largest emitter of all the provinces.

Current Emissions: 76 Mt in 2018, 12% higher than in 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 65.4 tonnes

Climate Strategy: The government hasn’t set out a 2030 target for emissions reductions, but it has adopted a climate plan that focuses on reducing dependence on coal-fired electricity, encouraging energy efficiency and supporting emerging technologies like small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs), which the province is hoping could eventually displace fossil-fired power on the grid and in industry.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: While challenging the federal carbon tax to the Supreme Court, Saskatchewan introduced its own levy that covers all industrial emitters, with the exception of power producers and natural gas pipelines – roughly equivalent to Ottawa’s plan. The federal system applies where the province exempted industries.

Long Shot: Saskatchewan has been a leader in development of carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) and has been banking on it to reduce its fossil-fuel footprint. It supported a CCS project at one unit of its Boundary Dam coal-fired power station, as well as the Weyburn project that uses carbon dioxide to stimulate oil production but then sequesters the CO2 underground. Saskatchewan, which has large reserves of uranium to fuel nuclear power, has also joined Ontario and New Brunswick in an agreement to support the development of controversial SMRs, which have some major hurdles to clear if they are going to be widely commercialized.

Blind Spot: The province relies on coal for 30% of its electricity and is considering replacing coal with natural gas. The publicly owned utility SaskPower hopes doing so will help cut its emissions by 40% from 2005 levels by 2030. However, a reliance on gas will make it difficult to move beyond that 40% target.

Projected Emissions: Saskatchewan’s emissions are projected to decline by 14% from a 2015 peak by 2030, falling back to 2005 levels.

Grade: D+

Manitoba

Manitoba is the largest emitter of the smaller provinces, despite having a major advantage with its massive hydroelectric resources.

Current Emissions: 22 Mt in 2018, 8.3% higher than in 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 16.3 tonnes

Climate Strategy: Manitoba’s Progressive Conservative Premier Brian Pallister announced last March that he would implement a $25-per-tonne carbon tax in his province on July 1, 2020, but delayed that for a year because of the COVID-19 pandemic. The province has established what it calls a carbon savings account, a series of three five-year periods, each of which will have its own GHG reduction target. The goal for the current 2018 through 2022 period is a cumulative 1 Mt of emissions.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: Manitoba’s biggest contribution could come by supporting interprovincial transmission with Saskatchewan, Ontario and even Alberta in order to move low-carbon hydroelectricity into those provinces.

Long Shot: Manitoba proposed a carbon tax plan that would have established a flat $25-per-year levy, unlike the federal tax that now applies, which sits at $30 per tonne and is due to rise to $50 in 2022. The federal Liberal government did not endorse Pallister’s plan.

Blind Spot: Agricultural emissions have increased since 1990, largely because of expansion of Manitoba’s hog and cattle industries. The province has the highest proportion of agriculture emissions in the country, at 30%, compared to only 8% for Canada as a whole.

Projected Emissions: The federal government projects Manitoba will reduce its emissions by 10% between 2005 and 2030, well short of the 30% national target.

Grade: C-

Ontario

With the country’s largest population, Ontario remains Canada’s second-largest GHG emitter. Climate change has been on the back burner since the Progressive Conservative government came to power determined to dial back the ambition of the previous Liberal government.

Current Emissions: 165 Mt of GHGs in 2018, down 19% from 2005 levels

Emissions Per Capita: 11.5 tonnes

Climate Strategy: After the 2018 election, Premier Doug Ford’s government killed the existing cap-and-trade plan and slashed the energy-efficiency efforts that it financed. In 2020, Ontario replaced the federal carbon price on industrial emitters with a provincial one that will be somewhat less costly to industry than Ottawa’s version. Ford remains a vocal critic of the Liberal carbon tax and rebate plan. The PC government released a review of its plans, but that focused on the carbon levy on industry as well as a marginal increase in the amount of biofuels mixed with gasoline or diesel. The March budget bolstered the province’s significant budget for transit and noted that the Ontario Securities Commission would be consulting on a recommendation to set a mandatory disclosure regime for climate-related financial risks.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: Ontario’s big declines came between 2005 and 2014, when the province retired its coal-fired power stations, a policy that caused one of the largest declines in GHGs in North America. There’s been virtually no improvement since 2014, according to figures released by Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC).

Long Shot: The government has offered support for technologies like the new-breed SMRs and hydrogen fuel cells that could play an important role in transitioning the economy to zero-carbon. However, it’s uncertain if or when either of those technologies will be commercially competitive and scaled up. It’s unlikely either will have much impact before 2030. In a more certain bet, Ontario is subsidizing North American carmakers’ plans to build electric vehicles in Ontario.

Blind Spot: Ford’s government cancelled renewable energy projects that had been approved but not built, a move that will eventually require the province to rely more heavily on natural gas, which means higher emissions. In a review of the province’s climate strategy, the Toronto-based advocacy group Environmental Defence said the Ford government had failed to take meaningful action to reduce GHG emissions. A spokesman for Environment Minister Jeff Yurek did not respond to several requests for comment.

Projected Emissions: ECCC projects that, given current trends, Ontario will still be emitting 160 Mt in 2030, for a decline of only 22% versus the Conservatives’ own target of 30%.

Grade: C-

Note: Numbers may not sum to the total due to rounding. Source: Environment and Climate Change Canada Report 2020. Historical emissions data comes from National Inventory Report 2020.

Quebec

Quebec is Canada’s third-largest emitter, though decisive climate-action plans contributed to a significant GHG decline between 2005 and 2016. Emissions have since rebounded as a result of the strong economic growth the province experienced between 2016 and 2018.

Current Emissions: By 2018, GHG emissions were just 4.1% lower than they were in 2005.

Emissions Per Capita: 9.4 tonnes

Climate Strategy: Quebec Premier François Legault boasts that his province has the most ambitious climate plan in North America, with a target of reducing emissions by 37.5% below 1990 levels by 2030. The most recent plan released by the Coalition Avénir Quebec (CAQ) government would get the province only 42% of the way to its 2030 goal. However, the government will introduce additional measures and is expecting more ambitious action from Ottawa and municipalities to help close the gap, says Geneviève Richard, a spokesperson for Environment Minister Benoit Charette.

“Quebec’s plan is ambitious because it aims to initiate a real transformation of its economy towards a greener and more resilient economy, which is a necessary condition for achieving its climate objectives,” Richard says.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: The province has one of the most aggressive climate plans in North America, especially in the area of electrifying transportation, with rebates for EVs and an aggressive program for building charging stations. Quebec administers its own cap-and-trade program and trades emission credits with California in the Western Climate Initiative, which Ontario had joined but pulled out of under the Ford government.

Long Shot: It remains to be seen how Quebec’s cap-and-trade plan – which is essentially a carbon-pricing measure – is affected by the Liberals’ proposed increase in the carbon tax to $170 a tonne. The issue is whether the increase in the federal price would require greater stringency from the province’s cap-and-trade system.

Blind Spot: The CAQ government tends to rely on incentives and subsidies for industries rather than regulations that would provide a more certain outcome.

Projected Emissions: Based on measures in place in 2019, ECCC projected Quebec’s emissions would be 16.3% lower than 2005 levels in 2030, though Richard says Quebec’s plans should reduce emissions by 37.5% below 1990 levels. That’s more than enough to meet the current federal target of 30% below 2005 levels. However, should the Liberals adopt a more aggressive target of 40% below 2005 levels, Quebec will be asked to do more.

Grade: A-

New Brunswick

New Brunswick saw the largest percentage decline in GHGs among all provinces between 2005 and 2018. The drop resulted from a combination of policy choices and a stagnant economy that saw major restructuring in the forestry industry.

Current Emissions: 13 Mt in 2018, down 34% since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 16.9 tonnes

Climate Strategy: New Brunswick is working with the federal government and other provinces to decarbonize its electricity sector. It has funded energy-efficiency programs that have saved energy costs and emissions. The province’s 2016 climate plan calls for the province to reduce emissions to 10.7 Mt by 2030 from 20 Mt in 2005.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: New Brunswick introduced its own carbon tax that was approved by the federal government in 2020, even though its system covering industrial emitters is far weaker than Ottawa’s own backstop approach. The federal government must approve provincial levies on a regular basis and will have to revisit the New Brunswick approval as federal prices rise.

Long Shot: The province is in discussions with Ottawa and other provinces about a proposed “Atlantic loop” that would connect the four eastern provinces – and possibly Quebec – in a single power market. The additional transmission capacity could help New Brunswick reduce its dependence on the Belledune coal-fired station, though the government worries about the loss of jobs and revenue at provincially owned New Brunswick Power.

Blind Spot: On the consumer side, the province introduced a carbon levy but reduced the sales tax on gasoline and other fuels, meaning the pump price rose by only two cents a litre. Given that a quarter of its emissions come from transport, they’ll have to try other ways of curbing carbon in a heavily rural province where people rely on their vehicles.

Projected Emissions: New Brunswick is on a path to see its emissions fall by 50% between 2005 and 2030, according to ECCC.

Grade: B-

Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia has been a leader in climate action in Atlantic Canada. Recently elected Liberal Premier Iain Rankin promises to put in place new measures to drive a clean-energy transformation.

Current Emissions: 17 Mt in 2018, down 26%

since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 17.7 tonnes

Climate Strategy: The province implemented its own cap-and-trade system, which the federal government accepted as equivalent in ambition to its own backstop.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: The province has adopted aggressive energy-efficiency programs, expanded renewable power and slashed its dependence on coal for electricity from 76% in 2007 to 53% in 2018. Rankin initiated a program to provide up to $3,000 in rebates for buyers of electric vehicles.

Long Shot: The province has been touting the potential of tidal power for years without much result, in terms of actual electricity flowing. It now has a goal of generating 300 MW from Bay of Fundy tides.

Blind Spot: Nova Scotia still relies on coal-fired electricity and plans to phase it out well after 2030, when more hydroelectric power from Newfoundland and Labrador becomes available. Rankin, who became premier in February, vowed during the leadership campaign to end coal use by 2030. Despite that promise, Nova Scotia Power plans to spend $30 million on improvements to its coal-fired generating units to keep them running smoothly.

Projected Emissions: Nova Scotia is on track to reduce its emissions by 56% between 2005 and 2030, according to projections from ECCC.

Grade: A

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador’s economy remains tied to its offshore oil industry and the much-troubled Muskrat Falls hydroelectric power project.

Current Emissions: 11 Mt in 2005, up 5.6%

since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 20.9 tonnes

Climate Strategy: The Liberal government in Newfoundland and Labrador has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.The Liberals, under Premier Andrew Furey, won a slim majority in the general election that was disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic and concluded in late March.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: The provincial government is counting on low-emitting power from the Muskrat Falls project, which began flowing electricity last fall after delays and massive cost overruns. Newfoundland and Labrador will reclaim ownership in 2040 of the Upper Churchill hydro development, which has been owned by Hydro-Québec under a deal that Newfoundland has sought to reopen for years.

Long Shot: The offshore oil industry association endorsed the government’s commitment to a net-zero target. However, it said producers will not be able to completely eliminate GHG emissions and will have to purchase credits to offset what they can’t avoid.

Blind Spot: Transportation remains the largest source of emissions on the Rock, at more than one-third of the total. With a commitment to increased hydroelectric supplies, the financially strapped province could find innovative ways to encourage a move to electric vehicles.

Projected Emissions: Newfoundland and Labrador is on pace to reduce emissions by 10% between 2005 and 2030, compared to a 30% national target.

Grade: C

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island has relatively low emissions given the lack of large industrial sources, but its household emissions per capita are the highest in the country.

Current Emissions: 1.7 Mt in 2018, down 19%

since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 11.4 tonnes

Climate Strategy: P.E.I. has adopted a plan to become net-zero by 2040, with a vision to become the country’s first province to essentially eliminate GHG emissions, though that includes the use of offsets. The province has invested significantly in renewable power.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: In December, the legislature unanimously approved the Net Zero Carbon Act, which enshrines the target in law and requires yearly accounting to track progress.

Long Shot: Much of P.E.I.’s emissions come from the transportation sector. Policies like gas-guzzler taxes and preferential parking and rebates for EVs could help reduce that figure.

Blind Spot: To meet its lofty goal, it will need more aggressive programs to decarbonize transportation, agriculture and buildings. As an island province particularly vulnerable to rising water levels, P.E.I. has to accelerate its efforts to prepare for the impacts of climate change.

Projected Emissions: P.E.I. had GHG emissions of

2 Mt in 2005 and is projected to reduce them by less than 1 Mt by 2030, according to the federal government.

Grade: B+

Yukon

Yukon has seen a big increase in emissions from transportation in the last decade, with GHGs in the transportation sector up 14%

between 2009 and 2017. Overall emissions in the territory remained flat over that period.

Current Emissions: 0.6 Mt in 2018, a 14% increase since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 14.8 tonnes

Climate Strategy: Yukon has set a target to reduce emissions from key sectors – including transportation, heating and electricity generation – by 30% below 2010 levels by 2030.

Best Attempt at Curbing Carbon: The territory is working with the federal government to support energy efficiency and renewable-energy projects in remote communities to lessen their dependence on diesel by 30% by 2030, including meeting 50% of heating needs from renewable sources.

Long Shot: Yukon is investing in transmission and micrograms with the aim of decarbonizing its grid to become 97% fossil-free by 2030.

Blind Spot: Thawing permafrost could release huge amounts of methane into the atmosphere. Mining is a major driver of Yukon’s energy demand, and, as the Canada Energy Regulator notes, the opening and closing of mines can dramatically affect electricity consumption.

Projected Emissions: The federal government projected Yukon could reduce its emissions

by more than half between 2005 and 2030.

Grade: B

Northwest Territories

The Northwest Territories relies heavily on GHG-emitting diesel for heating, power and transportation. It will have to cope with the impacts of a climate that is warming faster than the global average.

Current Emissions: 1.2 Mt in 2018, a 22% decline since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 26.9 tonnes

Climate Strategy: The N.W.T has a target to reduce its carbon emissions by 30% from 2005 levels by 2030. Many communities rely heavily on diesel and are investing in renewable-power projects to lessen that dependency.

Long Shot: Some nuclear industry advocates argue that remote communities will benefit from the commercialization of small modular reactors.

Blind Spot: Thawing permafrost could release huge amounts of the powerful GHG methane into the atmosphere.

Projected Emissions: The federal government projects N.W.T. emissions could fall by nearly half between 2005 and 2030.

Grade: B

Nunavut

Inuit hunters and community leaders say they are already seeing changes in the Arctic climate that will disrupt traditional land-use practices. The territory’s household and land-based emissions are also rising.

Current Emissions: 0.7 Mt in 2018, a 24% increase since 2005

Emissions Per Capita: 18.2 tonnes

Climate Strategy: Nunavut aims to displace some of that reliance on diesel, in particular with community-led renewable-energy projects.

Long Shot: With rapid population growth, Nunavut has seen its use of fossil fuels climb, with every community dependent on diesel for electricity, heat and transport. In the 2019 election, the Liberal Party promised to end the territory’s dependence on diesel by 2030.

Blind Spot: Thawing permafrost could release huge amounts of methane into the atmosphere.

Projected Emissions: ECCC projects Nunavut emissions, which were 0.7 Mt in 2018, will grow to 1 Mt by 2030.

Grade: B-

Shawn McCarthy is an Ottawa-based writer who focuses on climate change and the low-carbon energy economy.

From Corporate Knights Spring Issue, available April 21, 2021.