Last November, Typhoon Haiyan left a swath of destruction through Southeast Asia, flattening buildings and killing and maiming thousands of people. The suffering was exacerbated by a thwarted emergency response. In places like the Philippines, survivors endured hunger, thirst, exposure and a dearth of medical aid for days while disaster response teams – military and civilian – were bottlenecked at airports. Key infrastructure was destroyed, so teams were prevented from delivering their life-saving cargo. Aircraft couldn’t land. Vehicles couldn’t safely pass through the razed landscape.

Despite ongoing technological progress throughout the aeronautical industry, the area of air transport that remains grounded is one where the need – often caused by disasters like Typhoon Haiyan – is the greatest. Ideally, what is required is an aircraft that can land and take off without an airstrip, carry tonnes of supplies and personnel, is stable once it drops its payload (eliminating the need for ground crew), has a small horsepower engine that is frugal on fuel, can travel thousands of kilometres and is tough enough to withstand rough weather and even gunfire.

An international horse race to commercialize such a craft has pitted established aeronautical corporations like Lockheed Martin against dynamic entrepreneurial innovators like California’s Worldwide Aeros and Canada’s Solar Ship. The demand for a low-maintenance, dependable cargo craft nimble enough to navigate mountains and hills and land on uneven ground, ice, snow and water comes not only from military and government, it also comes from the mining, oil and gas sectors and isolated aboriginal groups.

The key difference between such a vessel and, say, the venerable Goodyear blimp, is the ability to transport huge payloads, says Tim Kenny, director of engineering at Worldwide Aeros, which is headquartered in Los Angeles. The company is one of the frontrunners in the development of such an airship, thanks largely to eight years of financial backing by the United States Department of Defense and NASA.

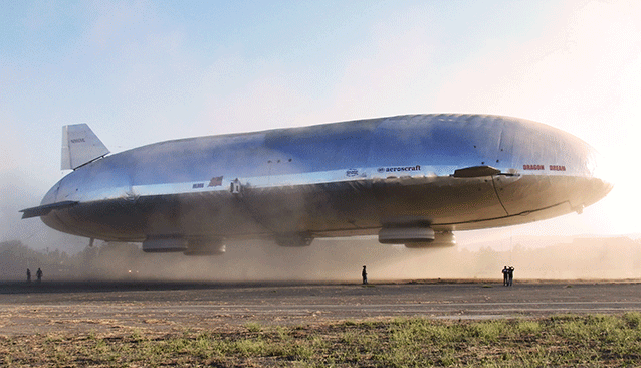

One of Worldwide Aeros’ flagship vessels is called the Aeroscraft, which underwent extensive field-testing last year but won’t be ready for commercialization until 2016. The 70-metre-long vessel has been built with unique features enabling it to fly in and out of remote areas that a helicopter or plane can’t safely access, Kenny says. “You could take in a whole platoon – about 30 or 35 guys – with vehicles and supplies, all at one drop.”

Helium highs

The Aeroscraft has long been in development and features vertical takeoff and landing, allowing it to manoeuvre in mountainous and heavily treed areas. It also boasts speeds of nearly 185 kilometres per hour. Called a hybrid, the craft is a combination of lighter-than-air technology, meaning it gets the majority of its lift from a gas like helium, which is contained in a highly engineered skin made of a material like Kevlar.

A smaller percentage of its lift comes from heavier-than-air technology: gas engines and aerodynamic wings. One of the design features that Worldwide Aeros has developed and patented is called control-of-static heaviness (COSH), enabling vertical ascent, descent and hovering. Equally importantly, COSH stabilizes the craft after it unloads, Kenny explains. COSH technology was inspired by submarines, which compress air to allow water in to create ballast for descent. For ascent, the compressed air is released, forcing the water out. With the Aeroscraft, the helium is either compressed or expanded by allowing air into specially designed envelopes in the balloon, creating upwards and downwards mobility. “We never have to dissipate helium or exhaust it outside,” Kenny says.

Since the military has provided the majority of financial backing, Worldwide Aeros has focused on fulfilling its demands and needs with a workhorse vessel that is expected to command annual lease fees of $25 million or $55 million, depending on airship size. But the company is also drafting plans for the creation of recreational aircraft for high-in-the sky casinos and wilderness excursions for well-heeled tourists.

Competing with Worldwide Aeros is U.K.-based Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV). It has developed several prototypes that are capable of landing on a variety of surfaces, including ice, desert and water, according to spokesperson Chris Daniels. HAV even created a lake, funded by the U.S. Navy, at its U.K. facility for testing water landings of a 15-metre-long prototype.

The HAV’s 92-metre airship can carry a payload of 50 tonnes. Engineers are working on scaling up, creating a 90- to 120-metre-long aircraft with a payload potential of 200 tonnes – enough to carry vehicles and other heavy equipment. “The bigger they are, the more proportionally they can lift,” says Daniels. “That’s why the airships of the 1920s and 1930s were so massive.”

Kevlar edge

Those were the halcyon days for airships, an era that ground to a halt when the massive hydrogen-filled Hindenburg exploded in 1937 and left 36 people dead. Hydrogen is highly flammable while helium, used in today’s airships, is not. But hydrogen is not necessarily as dangerous as the tragic accident implied. The Hindenburg’s biggest weakness was the material used to contain the hydrogen, on top of the fact that in those days it didn’t have high-tech radar, advanced weather forecasting, GPS and many other gizmos commonly used today.

That, says Daniels, is a key reason modern dirigibles are different. Today’s airship skins, for example, are virtually indestructible. Made of a lightweight, carbon-fibre Kevlar weave, airship skins have undergone gruelling testing. One dirigible was fired at 200 times with 50-calibre bullets and stayed inflated for two hours, he says.

The creation of a viable commercial industry of high-payload hybrid aircraft is tantalizingly close, and HAV, like Worldwide Aeros, is also planning luxury travel airships. But the more immediate need is in northern Canadian aboriginal communities and with industries like mining. This would include delivering fuel and supplies and flying people in and out of remote First Nation communities, many of which have expressed strong interest in the idea. With an airship that is 100- to 120-metres long, “you could carry 200 people,” Daniels says.

A few years ago, HAV negotiated the sale of two aircrafts with Canadian company Discovery Air, which provides aviation and logistics services in northern environments. That deal was never consummated. Nonetheless, the vessels are a natural fit with Canada’s rugged and desolate wilderness. HAV’s “long-endurance” aircraft can stay airborne for five days, providing a platform for geological surveys, surveillance and academic research such as monitoring animal migration and melting rates of Arctic ice packs.

HAV is also refitting a long-endurance aircraft that it sold to the U.S. Army for work in Afghanistan in 2012. The vessel was grounded after one 90-minute maiden flight, a result of budget cuts and the accelerated withdrawal plans of American forces from Afghanistan. But HAV, in what could be described as the deal of a lifetime, bought back the $100 million craft for $300,000. It plans to use the vessel as a demonstration craft to help sell a new generation of models in 2016. “We are currently dealing with interest from some Canadian mining companies,” says Daniels.

Solar assist

The company faces tough competition from Toronto-based Solar Ship, which is developing three prototype airships with different cargo capacities. Some Solar Ship prototypes are solar-electric powered, which has less range and carrying ability than a hybrid airship. However, the company is also developing its own hybrid, utilizing both solar and gasoline power with customized electric motors – a compromise between the twin demands of sustainability and efficiency, says founder and CEO Jay Godsall.

Solar Ship, which is focused on testing its smallest hybrid airship called the Caracal, is carving an aeronautical niche in Canada that piggybacks on the venerable northern bush plane system. Last year, this objective was bolstered by the injection of a $2.2 million grant from Sustainable Development Technology Canada, which has helped considerably to refine a prototype that can dependably service remote communities and the increasing needs of mining companies. Godsall says that the demand is accelerating due to climate change. Canada’s famous ice road system – the main conduit for goods and services to the North – is deteriorating due to warming temperatures.

Solar Ship’s aircrafts are nimble, requiring a short runway for takeoff and landing –100 metres with a full payload and 50 metres empty. Solar Ship is also developing amphibious aircraft that, like HAV’s prototype, can land and take off from water. Its Caracal airship, meanwhile, has come to the attention of the World Health Organization, which is exploring use of a prototype for delivery of medical supplies to strife-torn nations in Africa, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi. The immediate plan, says Godsall, is to start training pilots who already fly with non-governmental organizations like Mission Aviation Fellowship and the Flying Doctors Society of Africa.

Global challenges like extreme weather events and military conflicts are, unfortunately, not going away. This will accelerate the demand for the dirigibles currently being engineered in hangars around Canada, the U.S., Europe and the U.K. First seen floating above the English Channel in 1785, then reincarnated in various permutations over two centuries, it seems the time has finally come for airships to fill the skies.