Pursuing an MBA has long been seen as a high-reward option for business-minded individuals and societies alike. But when it comes to addressing today’s global issues, it’s quickly becoming a luxury in terms of time and money.

Fortunately, some community college and privately funded start-up programs have figured out that developing real-world experience right out of the gates is more important to becoming a successful entrepreneur than time spent in the classroom.

North American students have racked up a mountain of debt over the last decade, and many of those are MBA students. Tuition for a two-year MBA can range from $10,000 to well over $60,000, depending on the school.

Sitting at $1.2 trillion, college debt is the second-highest form of private debt in the U.S. behind mortgages. It’s no wonder that economists and debt-rating agencies such as Standard & Poor’s have warned that student loans could be the next economic bubble.

In Canada, the picture is less extreme, but still quite dim. According to the latest Statistics Canada survey, student debt grew 24 per cent between 2005 and 2012, leaving one in eight families paying student debts with a median value of about $10,000.

Aside from making it impossible to buy houses and start families, debt is holding young people back from pursuing projects that could help solve the world’s problems, says Danielle Strachman, program director at the Thiel Fellowship.

When graduates come out of college, they need to service their debt first, which means that they need a job that pays well, she says. “Most people say their jobs are temporary, but after a while, it becomes difficult to turn around and say ‘I’m going to work on that project I wanted to do when I was 18.’ ”

With the motto “some ideas just can’t wait,” the fellowship gives creative and motivated young people $100,000 to focus on a project, research or self-education.

Since the program began in 2011, 58 organizations and companies have been founded and are still running. The fellows have raised over $100 million in investments, grants and partnerships and created jobs for over 250 employees.

The fellowship teaches young people that the best way to test an idea is to put it out on the market and learn from one’s mistakes, says Strachman.

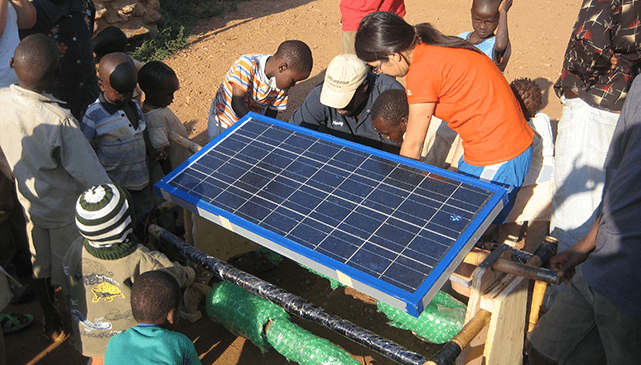

Eden Full, a fellow in the program’s first cohort, developed a device called SunSaluter, which allows solar panels to rotate with the sun, generating up to 40 per cent more electricity.

While a similar technology already existed, Full saw an opportunity to lower the cost, create a more intuitive design and start a non-profit organization that would allow local residents to start for-profit businesses without much technical knowledge.

But when the start-up launched in Uganda and Tanzania in 2012, Full found that neither country was the right fit for the early phases of the project. After realizing her mistake, she relocated the project to India in 2013, built a team and secured grant funding.

The company now has a manufacturing base in Bangalore, and has raised over $250,000 in grant money and deployed over 70 SunSaluters to 10 different countries.

But not everyone can so easily secure $100,000 to take two years off from school and pursue a dream. And that is where community colleges step in, says Andrew Gold, a business professor and social entrepreneur at Hillsborough Community College (HCC) in Tampa, Florida.

Entrepreneurship students at HCC are expected to realize a business idea or re-strategize and pursue something else within 15 weeks. While this may seem like an unrealistic expectation, Gold says the accelerated pace of the program is the most important part. It relies on the Lean Startup methodology, which requires entrepreneurs to build a boiled-down product as quickly as possible, show it to consumers and redesign the product based on the feedback.

In MBA programs, business students are typically taught to write business plans and tell people why their ideas are great in the hope that investors will come on board, says Gold. That is a flawed and broken process, especially if the product is not tested on the people who will be buying it, he says.

“You don’t build anything just because you have a feeling that someone is going to want it…. What most cutting-edge entrepreneurs are doing today is learning to fail quickly.”

While failing can be scary and costly, Gold says, community colleges provide a safe and affordable environment for all types of people to test their ideas with support from experts who they would otherwise not have access to.

Community colleges do a lot of hand-holding, and when you break down the number of class hours and face time with professors, the one-semester entrepreneurship certificate at HCC costs $9.12 per hour – far below what it would cost to hire a consultant, he says.

A big part of transitioning to a sustainable future is equal access to strong education, says Todd Cohen, director of the Sustainability Education and Economic Development Center, an initiative of the American Association of Community Colleges. “Community colleges are made for the working mother to come back to school or for a mid-career worker who realizes they want to go green,” says Cohen. “It opens up the door to many more types of people.”

Community colleges are also willing to train entrepreneurs who want to start small- or medium-size businesses that four-year business programs may not be interested in, says Gold.

As the chief executive of a tech startup without an MBA or university degree, Full says the challenge is mostly a mental one.

“Some of the hard part is knowing that you are on a different path from other people and positioning yourself in a certain way so that people don’t think you’re weird because you didn’t do what everyone else did,” she says.

The goal of the Thiel Fellowship, explains Strachman, is to set young people on a radically different trajectory and prevent more 30-year-olds from coming out of post-graduate studies saying “I wrote that thesis, but now what is my life about?”