Since the 1970s, sulphur-dioxide emissions from the Inco nickel smelter in Sudbury, Ont., have shrunk 90 per cent. That achievement cost $1 billion. Now, the current owner, a subsidiary of Brazil-based Vale SA, is spending another $2 billion to reduce the remaining emissions by about three-quarters.

Vale’s Clean AER (Atmospheric Emission Reduction) project seems a high price to pay for a relatively small result. It’s necessary, the company says, to comply with pollution limits imposed by the Ontario government. Plus, it says, the project is “simply the right thing to do.” It means cleaner air, 1,300 jobs at peak construction, “and a sustainable future for our operations.” That’s the new reality of mining: Spurred by tougher regulations and public pressure, leading companies are greening their operations to ensure they can continue to operate and expand.

The changes improve the environment and the bottom line – usually cutting costs and often producing profitable new resources. And they’re essential for the industry to meet increasingly stringent, albeit informal, conditions for a “social licence” to operate, says Ben Chalmers, vice-president, sustainable development, at the Mining Association of Canada, whose 36 members operate nearly half of Canada’s 200 mines. “It’s a competitive advantage.”

“Mining companies can no longer extract resources without full consideration of the local environment, communities or lasting impacts,” says Dallas Kachan, executive director of the Vancouver-based Clean Mining Alliance, launched last spring to promote high-tech solutions to environmental challenges. “Those that ignore their corporate social responsibilities are instantly decried by shareholders, communities, NGOs and even government.”

These assertions seem at odds with the industry’s image. The Inco smelter became infamous in the late 1980s when sulphur emissions from its giant smokestack combined with precipitation to create acid rain, which decimated fish in cottage-country lakes north of Toronto and turned Sudbury into a treeless moonscape. And it wasn’t unique. At mines everywhere, toxins leaked from tailings ponds, rainwater leached acids from massive piles of waste rock into lakes and rivers, and clouds of pollutants streamed from smokestacks.

Many operators simply abandoned exhausted ore bodies, leaving toxic waste dumps and, eventually, immense cleanup bills like the estimated $500 million for 250,000 tonnes of poisonous arsenic trioxide under the former Giant gold mine, near Yellowknife, N.W.T.

Reports such as Canada’s National Pollutant Release Inventory and the American Toxics Release Inventory show mine emissions are dropping, and companies insist every new project will be environmentally friendly. Even so, critics decry the legacy of past practices and demand tougher regulations. They fear backsliding as governments push projects to boost job creation and cut their capacity to enforce regulations.

This summer, for example, the Yukon government stripped significant environmental conditions – including a groundwater study – recommended by the territory’s Environmental Assessment Board before approving a silver mining project of Vancouver-based Alexco Resource.

And new technologies and processes are being adopted slowly, according to a 2010 Natural Resources Canada report, which cited regulatory barriers, upfront costs and the industry’s conservatism as main reasons. It’s a “first to be second mentality” that’s not surprising given the financial, worker safety and environmental risks of innovation on mining’s massive scale, says Janice Zinck, manager of mine waste management and footprint reduction at Natural Resources Canada, which heads the federal government’s Green Mining Initiative. “The technology needs to be proven.”

Still, “there’s tremendous interest in the industry in becoming greener,” Zinck says.

Eight years ago, the mining association introduced Towards Sustainable Mining, or TSM, which requires members to track, improve and report on their impacts. The Mining Association of British Columbia has formally adopted TSM and industry groups in other provinces unofficially follow its principles.

The Prospectors and Developers’ Association of Canada promotes practices labelled e3 Plus, which, it tells members, “will result in improved environmental performance” and “help to preserve access to lands for future exploration and the development of new mines.”

Other countries have codes and some companies aim for ISO 14001 certification, which sets standards for environmental management and requires external audits.

The voluntary TSM code “goes above and beyond” regulations, Chalmers says. “It’s not the only way of achieving a social licence but however you obtain one, it’s critical.… Communities are looking for it.” That includes indigenous people, impacted by most mine projects. And, in Canada at least, “water boards are building it into approvals.”

Typical of large corporations, Teck Resources last year launched a sustainability strategy, and 10 of its 13 mines, all in Canada or the United States, have achieved ISO certification. Cliffs Natural Resources, of Cleveland, Ohio, has volunteered to undergo the most stringent form of provincial environmental assessment for its proposed $3.3-billion chromite mine and processing facility in Northern Ontario.

Many miners are adopting renewable energy to reduce costs and emissions and improve reliability. Toronto-based Barrick Gold has installed a one-megawatt solar farm at a mine in Nevada, as well as massive wind farms in Chile and Argentina.

The Diavik Diamond Mine has built four wind turbines with total capacity of 9.2 megawatts to generate electricity at its operation in the Northwest Territories, 300 kilometres northeast of Yellowknife. The turbines will reduce the amount of diesel trucked to the site by an ice road that because of warming weather is available for shorter periods each winter.

Vale and an Australian partner plan two wind farms – total capacity, 140 megawatts – to power iron mines in northern Brazil. Large wind and solar arrays are being installed at mines in Germany and China.

Canada’s three-year-old Green Mining Initiative, or GMI, is working with industry, universities and other research centres on more advanced methods to reduce energy consumption and waste generation from mining and refining; cut water use; develop better strategies for reclaiming old mine sites; and reduce environmental risks.

Projects include:

• The world’s first hybrid propulsion for loaders and other large underground equipment. Tests of a fuel-cell-powered loader are underway at mines in Arizona, Nevada and Quebec.

• A novel process to effectively extract gold from ore without the use of cyanide.

• Applying organic wastes from the pulp and paper industry and municipal collections on tailings to grow willows, canola and other potential bio-energy crops. The main tests are at the Vale and Xstrata Nickel mines in Sudbury, as well as a Goldcorp Canada property in nearby Timmins.

• Replacing Portland cement, which requires huge quantities of energy to produce, with mine site materials to stabilize rock that’s backfilled into mines.

• Ventilation on demand, which cuts energy consumption by delivering fresh air only as needed to underground work sites.

• Using alternatives to explosives to break rock.

• Reducing energy consumption in milling.

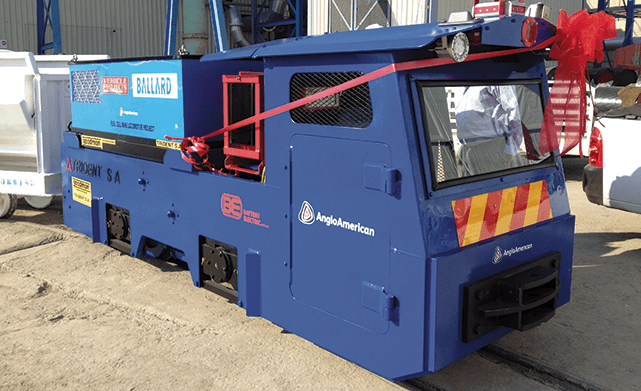

Outside the GMI, Anglo American Platinum last spring launched a prototype underground locomotive powered by fuel cells at its mines in South Africa.

The Clean Mining Alliance is on a similar track, Kachan says, aiming to promote “radical” solutions generated by its members to an industry “waiting to be revolutionized by clean technology.”

Solutions by alliance members include:

• American Manganese, a venture company based in British Columbia, says its refining process uses only 6 per cent of the energy of conventional high-temperature roasting. That will let it produce electrolytic manganese – essential for lithium-ion batteries and specialty steel – from low-grade ore at an Arizona property more cheaply than the high-grade resources in the dominant producer, China. The company also plans to generate power with heat energy from production of sulphur dioxide.

• Nevada Clean Magnesium, another B.C. junior, plans a Nevada mine that, to keep greenhouse gas emissions low, will recover energy from waste heat sources; use a technology that purifies carbon dioxide so it can be sequestered in abandoned oil wells; and provide slag to a cement producer to halve its energy consumption.

• Kemetco Research, a services company, is working on using bacteria to capture gold from ore without cyanide, and to stop acid rock drainage.

Outside the alliance, Toronto-based BacTech has a bacteria-based technique to clean up wastes at old mine sites. Its first commercial-scale project is near Snow Lake, Man., where a former gold mine left tailings that contain cyanide – and gold.

The company aims to detoxify the wastes and harvest gold in about a year, says president and chief executive Ross Orr. BacTech will pay for the cleanup and keep the gold – a profitable trade-off at current prices, he says.

Mines use billions of litres of water annually to extract ore from rock, cool machinery and suppress dust. Spills and tailings frequently pollute lakes and streams.

Barrick is among the companies aiming to reduce water intake through greater recycling, including treated wastewater, and the use of saline sources. At a mine in Chile, it’s using earthworms and bacteria to purify wastewater to a quality that’s safe for irrigation of food crops.

The American Manganese project is to include closed-loop techniques that cut water consumption, including filters made of advanced nano-materials that purify water and help to create tailings that, because they’re solid and inert, can be put back underground, eliminating the need for settling ponds and fear of contamination.

In fact, Kachan says, advanced materials “could one day lead to mining projects that produce no greenhouse gas emissions, emit benign tailings and return produced water to the natural habitat as clean, if not cleaner, than it was originally.”

New forms of mining promise to reduce the industry’s impacts. Last year, California-based Simbol Materials began extracting lithium carbonate, used for electric-vehicle batteries, from the hot, mineral-laden brine that bubbles from deep underground to fuel geothermal power plants along the San Andreas Fault. The company aims to supply 20 per cent of the world’s lithium market from this source by the end of the decade, without what it calls “ecologically dubious” mines.

Though mining can never be free of environmental impacts, it has plenty of room for improvement. Still, notes Zinck, the industry is making strides. “Its reputation is not what it should be. It’s not an industry that promotes its success stories … but significant improvements are being realized.”