After last month’s inaugural car face-off, May’s head-to-head contest pits the Chevrolet Bolt against the Honda Fit. Which is cheaper to own and operate over 10 years?

These comparisons are complicated by the widely varying prices of electricity and gasoline across Canada, as well as differences in how utilities charge for electricity. When forecasting over 10 years, it’s best not to take anything for granted so we didn’t factor in the current Federal government’s carbon tax scheduled increases, which reach $50/tonne by 2022. If we had included this, it would have added $917 to the cost of the internal combustion engine option over a decade. (See Face-off rules at bottom to see the rest of assumptions we made).

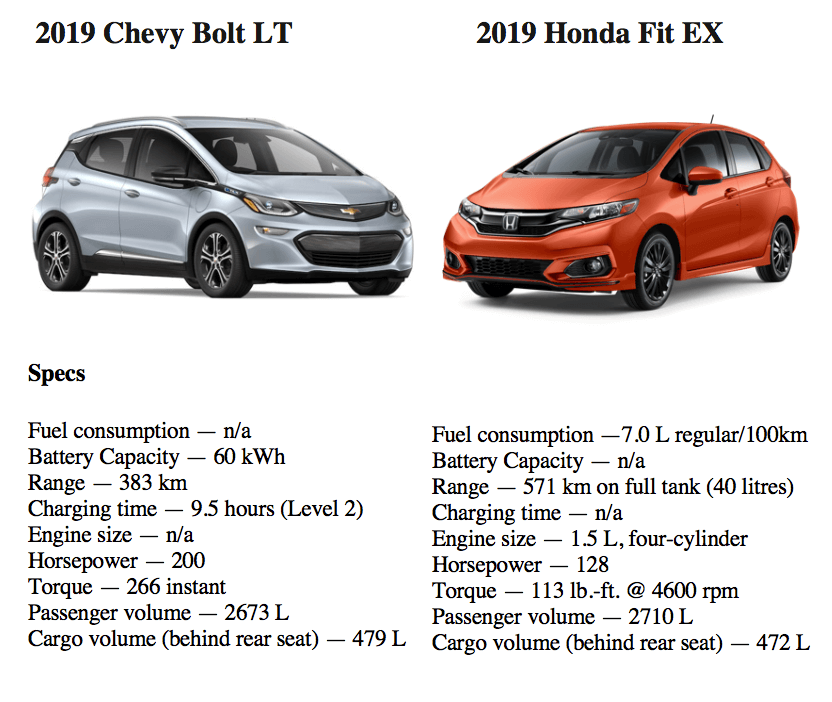

We picked the Honda Fit with the second-highest trim, the EX, to compete with the Bolt LT. The two vehicles offer similar features, but no navigation. That’s because the Bolt offers navigation only as an extra-cost option on its $49,800 Premier trim, while you can get it on a Fit for $24,390. With that price difference the Bolt wouldn’t stand a chance in the race.

The electric contender

CHEVY BOLT

Natural Resources Canada classification: Small wagon

The story: When Chevrolet launched the Bolt late in 2016, the company proclaimed it the first affordable EV with a range of 383 kilometres. That number meant drivers could do more than commute in the car without worrying about running out of juice. The only car that could run farther between charges was the Tesla Model S, which, for most drivers, was anything but affordable.

The Bolt is still pricey for a small car: Its rock-bottom Canadian list price is $44,880, although the new federal incentive, as well as those in Quebec and B.C., bring that cost down.

Other carmakers are catching up to the Bolt in range, value and price. For now, though, it sits at No. 3 in EV sales behind the Model S and the revamped Nissan Leaf in Canada (which we reviewed last month) and No. 2 in the United States.

The gas-powered competitor

HONDA FIT

Photo: Honda

Natural Resources Canada classification: Small wagon

The story: The Fit, introduced here in 2006 and now in its third generation, has been popular. Although, like most small vehicles, sales have been dropping.

Honda introduced a Fit EV back in 2010 that had a 20 kWh battery and a range of 130 kilometres. But the company committed to producing only 1,000 vehicles, offered only on lease in a handful of U.S. states and stopped production when it reached the quota.

A new Fit EV, with a 300-kilometre range, is promised for next year. The U.S. price is supposed to be under the equivalent of $26,000 (Cdn), which, if true, would change the price equation.

The face-off

Number crunching: So what are the real-world costs of ownership over 10 years? Here’s a bill for both cars.

Bottom line: The Bolt will be a slight jolt to the budget costing an extra $4,391 compared to the Fit, but you can take some solace in knowing that your personal carbon footprint would be 37.4 tonnes tonnes lighter than if you had burned ten years of gasoline in the Fit.

Face-off rules

- EV and ICE vehicles are compared according to Natural Resources Canada’s classifications.

- Initial cost is the vehicle’s suggested retail price, for the base model EV and the ICE’s trim that most compares in features. Canada’s national average sales tax is used (11.075%). Delivery charges and dealer fees are not included. Each vehicle is kept for 10 years, so depreciation is 100%.

- Fuel/power calculations are based on Natural Resources Canada (kWh/100km, L/100km combined HW/city).

- Each vehicle is driven 20,000 kilometres per year — the “rule of thumb” cited by Statistics Canada.

- The gasoline price is $1.28 per litre (latest CAA national average gas prices. The electricity cost is 10 cents per kilowatt/hour (population-weighted average electricity bill per province per 1000 kWh including taxes assuming majority of charging occurs during off-peak hours in NFLD, AB and ON).

- The lifetime maintenance and repair cost for an EV is about 50% that of an internal-combustion vehicle: $100 per month as an average for the ICE, based on data from Canada Drives Ltd.

- The $5,000 federal subsidy is deducted from the EV price. Provincial incentives — up to $8,000 in Quebec and $5,000 in B.C. — are not included, but EVs clearly fare much better in those provinces.

- The ICE buyer pays cash. The EV buyer pays the same amount in cash and borrows the cost difference at 5% interest, with a 72-month term.

- The cost of a Level 2 charging station, estimated at $1,745 ($995 plus $750 to install) is included as an additional cost (based on FLO Home™ system which retails for $995 with an average installation cost of $750). It is technically not needed, but since EVs take up to 60 hours to charge at Level I, it’s virtually a necessity.

- Tailpipe CO2 emissions based on NRCAN stats of grams/kilometre converted to tonnes (with assumption of 200,000 kilometres driven). We also counted the upstream emissions of producing, transporting, and refining crude oil into gasoline. EV emissions based on Canada’s electricity generation intensity with a national average of 140 g CO2/kWh (NRCAN). Note this is not a full lifecycle emissions calculation due to lack of readily available data by vehicle for emissions related to raw material production, manufacturing, transportation and decommissioning. Analyses that include these factors find that EVs have higher emissions footprints associated with sourcing some of the raw materials required for the battery, but on an overall lifecycle basis in low GHG intensity grid regions, an EV’s carbon footprint is about one-quarter that of its internal combustion engine counterparts.