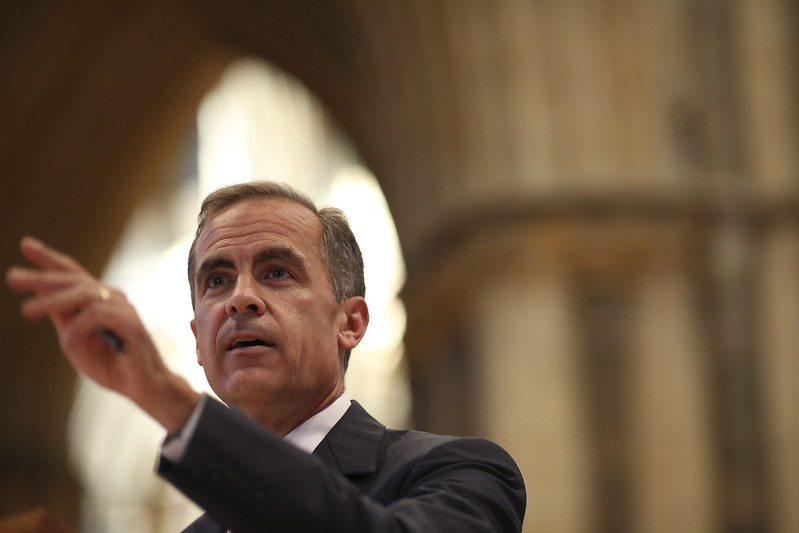

Just a year ago, Mark Carney inspired optimism among climate finance campaigners by founding a new alliance of banks and other financial institutions that pledged to decarbonize their portfolios.

More than 450 firms came together to commit to bringing their loan and investments down to net-zero by 2050 in what’s called the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). All together, these financial institutions managed more than US$130 trillion, and according to a recent progress report, they have grown to 550 firms, managing more than US$150 trillion.

But as the clock ticks down to COP27, next week’s UN climate summit in Egypt, much of that optimism has dissipated, as GFANZ announced last week, in a stunning disavowal of its original mandate, that it will not require its signatories to set rigorous science-based emissions-reduction targets in line with the United Nations Race to Zero campaign.

“It is disappointing that GFANZ is quiet quitting the Race to Zero,” said Paddy McCully, a senior analyst at Paris-based climate finance think tank Reclaim Finance, in a statement. “Banks and investors cannot wish away the terrifying math of the global 1.5°C carbon budget which has zero room for any new coal mines or oil and gas fields.”

In a statement released last week, GFANZ said that its “member alliances are encouraged, but not required, to partner with Race to Zero.” This reverses the position GFANZ adopted at its launch only a year ago by Carney, a former governor of the Bank of England (and Canada), and means the alliance’s members – made up of banking, pension, asset management and insurance networks – no longer must follow stringent requirements that include a recent mandate to end all new financing of oil, gas and coal projects.

Tracey McDermott, chair of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance (the banking member alliance within GFANZ), went a step further, assuring banking signatories they are free to set their own targets, regardless of guidance from GFANZ, Race to Zero or the banking alliance itself. “You, as members, must continue to set your own individual targets and make independent decisions as to how to meet those targets,” she said.

GFANZ’s credibility rested largely on the obligation by signatories to commit to Race to Zero, the UN’s key net-zero campaign. Race to Zero is made up of climate experts and non-governmental organizations around the world. With the goal of limiting global temperature rise to no more than 1.5°C, Race to Zero has called on its signatories to cut their share of carbon emissions by 50% by 2030 and to end new financing of fossil fuel projects.

Such commitments would have been a big pill to swallow for many GFANZ signatories, including US mega-banks JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Morgan Stanley and Canadian banks with large oil and gas loan books such as RBC, Scotiabank and TD. All are among the top 12 fossil fuel banks in the world.

It is disappointing that GFANZ is quiet quitting the Race to Zero.

-Paddy McCully, a senior analyst at Reclaim Finance

After these institutions and others threatened to leave GFANZ, the alliance backtracked on its Race to Zero requirement.

“Clearly, they [GFANZ] are giving in to their Wall Street members who have been reported as threatening to quit the alliance if they are expected to actually pull back on their finance for fossil fuels,” said McCully.

In its progress report, GFANZ maintained that its standards will remain vigorous, pointing to its voluntary guidance on net-zero transition plans, phasing out fossil fuel financing and measuring alignment with climate goals. “These voluntary commitments and actions collectively represent huge scale and high ambition,” it states.

However, without the threat of embarrassment from being thrown out of the alliance, GFANZ signatories can now adopt a wide range of CO2 metrics and targets even if their emissions rise. Six large U.S. banks fail to include both lending and underwriting in their emission targets, and most also rely on intensity-based targets, rather than absolute emission targets, according to a recent report from the Sierra Club. Canadian bank RBC also issued soft intensity-based climate targets a day before the GFANZ announcement. These intensity-based targets put the onus on borrowers to reduce the carbon intensity of their production but would still permit absolute bank emissions to rise if they finance higher production from those borrowers.

Calls for net-zero banking regulations mount

The GFANZ decision has strengthened a growing resolve by critics, academics and government advisors to push for financial emission regulations, in addition to voluntary initiatives.

“Going it alone, or just saying “trust us” is very risky,” tweeted Thomas Hale, professor of public policy at Oxford University. “For the same reason we see a growing push for putting net-zero alignment into regulation. Done well, regulation can help the private sector do this by establishing a clear and level playing field.”

“Financial institutions need to firm up emission reduction targets with internal implementation plans, then regulators need to enforce bottom lines for ambition and hold institutions accountable for delivery,” said Julie Segal, climate finance program manager at Canada-based Environmental Defence, in an email.

One of the emerging ideas to hold financial institutions accountable is to make it more expensive for them to issue loans or make investments in high-emission companies.

Gregg Gelzinis, associate director at the Center for American Progress, has proposed that regulators impose higher capital requirements on banks making loans or investments in high-emitting sectors and companies. This would require banks to set aside higher capital on these loans, providing a reserve against potential losses from fossil fuel assets, which are expected to be phased out over time. It would also reduce funds available for other lending, thereby cutting profit and giving an advantage to low-emission competitors.

The Climate-Aligned Finance Act, a bill proposed by independent Canadian senator Rosa Galvez, also proposes higher capital requirements for high-emission financing. Such a proposal is also being considered by the Bank of England.

It’s not clear whether this concept could be applied to pension funds, insurers and asset managers since they aren’t under the same capital requirements as banks. But for the bank sector, it could be a powerful incentive to clean up their balance sheets.

“If one thing is clear, it’s that banks understand and will respond to economic incentives,” says Amir Barnea, finance professor at HEC Montréal. “When financing the climate crisis will cost them money, they will budge.”

Eugene Ellmen is a former executive director of the Canadian Social Investment Organization (now Responsible Investment Association). He writes on sustainable business and finance.