The Canadian Cancer Society issued a news release earlier this month that, to my surprise, got zero mainstream media coverage. Queen’s University in Kingston had been selected to lead an international clinical trial of a new class of cancer drug. The trial was specifically aimed at non-small cell lung cancer, the most common form of what is the leading cancer killer in both men and women.

“This is one of the most significant research funding announcements in the history of Queen’s,” said the university’s principal Daniel Woolf. I learned later from a cancer society spokesperson that media are only interested in the results of clinical trials, not the launching of them – even if Canada is taking the lead internationally.

I’m biased. My father, Paul Hamilton, died of non-small cell lung cancer this past April, seven months after diagnosis. Like many people shortly after learning they have cancer – in his case, it was Stage 4 from the start – my dad got religion about the importance of healthy eating and other measures to boost the immune system. He was drinking dandelion tea. Taking melatonin to improve his sleep. Sprinkling turmeric on his food. Popping astragalus pills. Eating organic fruits and veggies.

But it didn’t take long for reality to set in. Healthy eating, even if it did boost his immune system a bit, wasn’t going to deal with the core problem – the cancer. It can’t hurt, of course, but in the end it was medication that bought him a few extra quality months, and that was considered a good outcome.

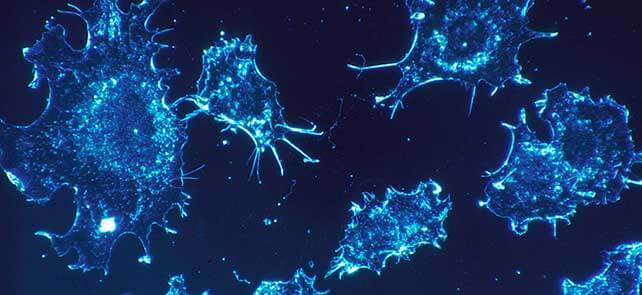

The reason why the immune system – healthy or not – is ineffective against malignant tumours is because cancer cells use a specific type of protein to cloak themselves. This makes them invisible to “killer” T-cells, the front line soldiers of our immune system. To use a Star Trek reference, it’s like the U.S.S. Enterprise trying to fight a cloaked Klingon Bird of Prey. There are miracles, of course, but the odds are never good – and life isn’t a TV show.

As Cancer Research U.K. tells people on its website, “Your immune system is very unlikely to be able to fight off an established cancer completely without help from conventional cancer treatment, although there are very rare documented cases of cancers just disappearing.”

Still, you never give up hope. It’s like Lloyd in the film comedy Dumb and Dumber when he asks his love interest Mary if there’s at least a 1-in-a-100 chance she could ever fall for him. “I’d say more like one out of a million,” she tells him, to which Lloyd replies enthusiastically: “So you’re telling me there’s a chance? Yeah!”

The odds of defeating cancer can be 1-in-a-billion and you’d still cling to that 1. So I spent a significant amount of time learning about and navigating through the clinical trial system, hoping maybe – just maybe – there was some experimental wonder drug that might come to the rescue. A helpful woman coordinating clinical trials at Toronto’s Princess Margaret Hospital proved an invaluable resource, and it was she who told me about some promising new “immunotherapy” drugs in the clinical trial pipeline.

Immunotherapy is all about better harnessing the body’s immune system to kill cancer cells. I’d learned a little bit about this approach through my own research, but didn’t really understand its potential until I read the December 2013 issue of Science magazine, which declared cancer immunotherapy the scientific “breakthrough” of the year. “It’s an attractive idea, and researchers have struggled for decades to make it work,” the magazine’s editors wrote. “Now, many oncologists say those efforts are paying off.”

It’s also an empowering idea, one that gave my father comfort when we spoke about it. Instead of poisoning our bodies with chemotherapy, which weakens the immune system, immunotherapy levels the playing field so our T-cells have a fighting chance. I showed my dad YouTube videos showing T-cells under a microscope seeking out and destroying cancer cells. It’s really remarkable this goes on inside our bodies.

And this brings me back to the international clinical trial being led by Queen’s University. The drug being trialed is called MEDI4736, a monoclonal antibody developed by U.K.-headquartered pharmaceutical giant AstraZeneca. Up to 1,100 lung-cancer patients from Canada and around the world – people who have already gone through surgery and chemotherapy – will get a chance to sign up.

MEDI4736, to simplify it, doesn’t try to kill the cancer cells. What it does is de-activate the cloak that the cancer cells use to evade immune system detection. To continue with the Star Trek analogy, it’s like disabling the Bird of Prey’s cloaking system so the U.S.S. Enterprise can take it down with a battering of targeted photon torpedoes. That’s a heck of a lot better than randomly firing in hopes of hitting an invisible nemesis, but at the same time knocking out ships in your own fleet – which is pretty much what chemotherapy does, and not very well.

AstraZeneca boasts that MEDI4736 “holds potential to shape the future of cancer treatment,” and is optimistic the drug will be effective against a wide range of cancers, including pancreatic, gastroesophageal, head, neck and skin cancers. It’s not the only immunotherapy drug being tested. In fact, some drugs in this class have already been approved, and are proving quite effective, for use in patients with malignant melanoma. A few years from now, who knows what immunotherapy drugs will be treating – and possibly curing?

So what’s the sustainability angle? This is, after all, Corporate Knights, the magazine for clean capitalism.

Well, there isn’t really one – or at least not a strong one. AstraZeneca, as a company, has ranked well in past years on Corporate Knights’ Global 100, but it dropped off the list in 2014 and a re-appearance isn’t expected in 2015. Not that the company is a poor performer overall. Out of 171 publicly traded companies in its sector globally, AstraZeneca ranks Top 15 when measured across 12 key sustainability-performance indicators.

But more relevant to this discussion, the emergence of cancer immunotherapy gives us all even more reason to embrace lifelong healthy eating and a sustainable lifestyle, as well as avoid (reduce) the toxins and pollution in our environment that can be crippling to our immune system.

Under today’s cancer-fighting regime, our T-cells are battle-worn and struggling, but under tomorrow’s they promise to be the Navy Seals of cancer combat.

When it comes down to it, though, this is just an interesting story about an important Canadian-led clinical trial that needed to be written.