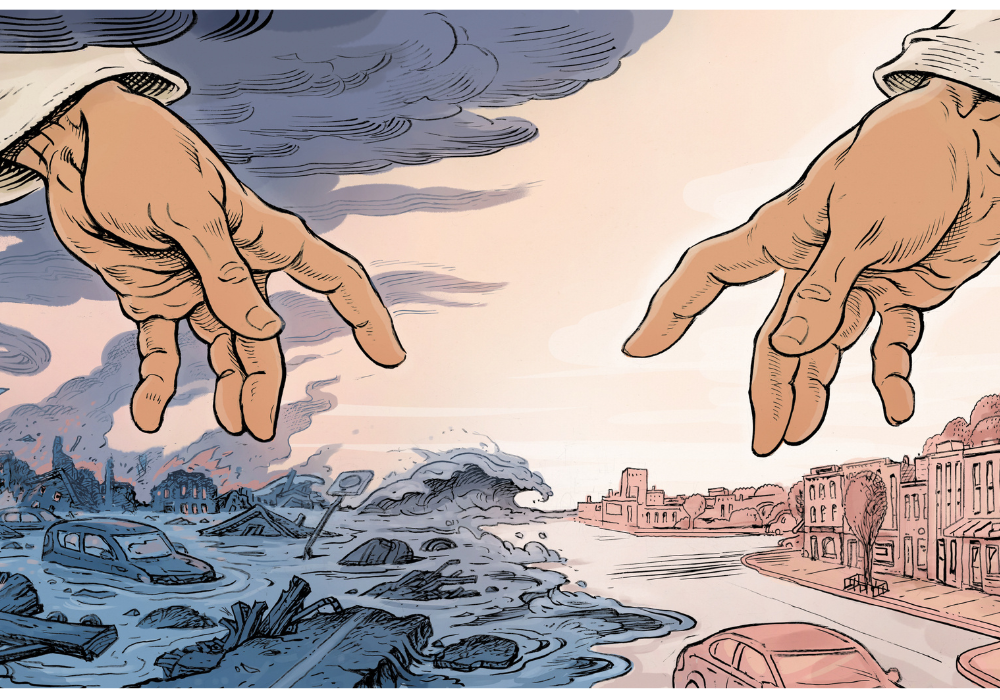

God’s ways are famously mysterious. They are also, in legal terms, highly destructive and annoying.

For nearly 500 years, whenever things have gone very badly – a storm sank your ship, say, or a drought killed your crops – and the normal course of business has been unforeseeably and uncontrollably disrupted, you could always blame your problems on an “act of God.” Dig into nearly any boilerplate contract for goods or services today and you’ll still find an all-purpose divine scapegoat, there to take the heat for catastrophes that no one could have reasonably anticipated or prevented.

It’s a good system: when shit happens, blame God. Now that we’ve pumped a few trillion tonnes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, however, God has grown less reliable as a fall guy. Courts rely on historical weather data to determine foreseeability when assessing act-of-God claims, but in the era of climate change, much of that data is no longer accurate. “You can’t keep calling things hundred-year floods when you have them three years in a row,” points out Richard Reizen, a partner at Gould & Ratner and chair of the firm’s construction practice.

In recent years, many lawyers like Reizen have called attention to the intrinsic tension in force majeure provisions – “force majeure” is a broader category of calamities that encompasses acts of God and includes things like war and strife – as the direct impacts of climate change add new layers of uncertainty across many sectors, while also opening doors to new opportunities for investment.

Construction isn’t the only industry where natural disasters and weather disruptions have increased the frequency of force majeure claims. “The climate is changing, and the law has to change with it,” says Hannetjie Marais, a legal advisor at Inlexso in South Africa who represents clients in the energy sector, where climate change affects renewables in particular.

Reizen and Marais are part of a cohort of legal professionals helping businesses transition to the new epoch of climate risk, alongside digital innovators in insurance and weather forecasting. Altogether, they are laying the groundwork to unleash the necessary capital for a new economy where climate adaptation and mitigation take centre stage.

The new force majeure

One way of tracking the increase in force majeure claims is by looking at the number of weather events with more than a billion dollars in damages, as the two tend to correlate closely, says William Droze, a partner at Troutman Pepper, a U.S.-based law firm. Data from the National Centers for Environmental Information shows that billion-plus events occurred on average 5.6 times per year in the 1990s, compared to 20.4 times per year over the last half-decade. In 2023, there were 28.

But the changes to the weather wrought by global warming aren’t all showstoppers like hurricanes and tropical storms. Climate change also alters global weather patterns in ways that aren’t as damaging as headline-making extreme events. Sometimes the wind blows less, not more.

A 2022 study of the resilience of renewable energy under a changing climate found that, under high-emission scenarios, “wind energy and hydropower production could decrease by as much as 40% in some regions due to climate change.” While other forecasts are less stark – the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has projected that average annual wind speeds could drop by 10% globally by 2100 – there’s no doubt that climate change alters wind patterns in ways that are unevenly distributed. For example, wind energy potential in India fell by 13% from 1980 to 2016 because of rising temperatures in the Indian Ocean.

The climate is changing and the law has to change with it.

— Hannetjie Marais, legal advisor to Inlexso

Marais says that shifts in weather patterns have also led to disappointing results for wind energy in South Africa. “What we’ve seen happening on the ground is that wind farms are not performing as expected,” she says. That sets the stage for legal disputes and potential appeals to force majeure over missed production targets. “You use 20-year historical wind data to decide what the power curve for a facility is going to be, and suddenly the wind simply stops blowing.”

Short-term wind droughts also pose an occasional threat. For example, in 2021, plummeting wind contribution forced the United Kingdom to temporarily reignite two mothballed coal plants. But the very next year, Britain’s wind farms produced record power, and its coal plants were ultimately shuttered for good in 2024.

Long term, hydropower production will fall steeply in some regions where climate change disrupts precipitation patterns, snowmelt dynamics and river flows, says Ahmed Osman, a senior research fellow at Queen’s University Belfast and the lead author of the 2022 study. China and South America will experience declines, and Portugal could see a 41% reduction in hydropower generation by 2050 due to reduced rainfall and reservoir capacity.

Diversified renewable-power sources across large geographic areas are capable of compensating for temporary wind or rain droughts or missed targets, but investors and operators of renewable projects need to be realistic about the risks. Marais says that for renewables to continue developing, they’re going to need force majeure protections that reflect the reality of a changing climate. “Because of climate change, businesses can no longer rely on historical weather information such as wind data to help develop an accurate financial model,” she explains.

Increasing granularity, greater flexibility

One way that lawyers writing contracts for renewable production and other industries can improve their defences against weather risk is to dig down into the details. “Engineers plan for sea walls and barriers to protect cities from future floods,” write Kristina Kopf Thomas and Briana James of the law firm Eversheds Sutherland. The same must be done for contracts, they argue. “We must look at how contractual provisions intended to address the extraordinary will function in a world where what was once unusual is now less so.”

The key, Thomas and James say, is to get specific. “Parties relying on boilerplate force majeure clauses may unintentionally find themselves responsible for unwanted risks,” they write. For example, if a builder is contracted to construct a development in a region where hurricanes are occurring more frequently, Thomas and James suggest describing the wind speeds and duration that would excuse delays or nonperformance, rather than hurricanes in general.

When he’s negotiating a construction deal, Reizen has learned to include “weather days” in the contract. “What I find most effective is to sit down, look at where you’re building, and put down a specific number of weather days that you actually put in the contract so that people can adequately plan,” he says.

It’s not always the direct impacts of extreme events that cause the greatest problems; sometimes the secondary effects create the most setbacks. “In California, when there’s a forest fire, you’re not just looking at the fact that it could come on your property,” Reizen says. “The bigger risk is air-quality days where, because of fires, people can’t work outside.”

Still, you have to strike a balance, says Mary Mbugua, founder and CEO of Risk Response Africa, a risk-management company in Kenya. Force majeure provisions should be “specific enough to address the risks at hand while also allowing for flexibility due to the uncertainties inherent in climate science.” Mbugua suggests that contracts should allow for adjustments as new scientific data or risk-modelling techniques emerge, as well as include provisions for periodic reviews and updates.

Hedging climate risk for the renewables market

Carefully written contracts can’t do all the work of protecting investments, and where legal recourse remains uncertain, such as in the wind-power sector, financial instruments can do a lot of the heavy lifting. “You can actually structure financial contracts where you can protect yourself against a downturn of the wind,” says Pascal Storck, head of technology at Vaisala, a global climate-intelligence firm.

In simple terms, it’s about skimming off the boom times to pay for the bust times. “You want to have a financial hedge where if you have less energy, you’ll have some compensation,” Storck explains. “In order to achieve that, you’re willing to give up some of your revenue in periods of abundance.”

We must look at how contractual provisions intended to address the extraordinary will function in a world where what was once unusual is now less so.

— Kristina Kopf Thomas and Briana James, Eversheds Sutherland law firm

Energy traders have been making weather-based bets since long before renewables achieved the level of market penetration they have today. Investors in coal, oil and natural gas markets have relied on predictive weather technologies for decades to forecast demand based on temperature. In simple terms, demand goes up in a hot summer or a cold winter, and vice versa. Savvy traders with a good almanac – that is, a service like Speedwell Climate in the United Kingdom, which has provided predictive models to players in these markets since the 1990s – make their bets accordingly.

Now, energy traders are diversifying their portfolios to include renewables and making bets based not only on demand but on supply. For example, if you know there’s a warm, windy winter on the way, then the value of gas will go down, because people will be burning less for heat and the energy supply from wind power will be greater.

The weather derivatives market, as it’s called, helps answer a fundamental question, according to Storck: “The weather is getting crazy because of the climate, so what do we do about it?” By converting climate risks into investment opportunities, these instruments can help de-risk renewable-power projects and create the stability for more capital to flow into the sector.

Halting the retreat of insurance

Obviously, insurance providers have a critical role to play in creating protections for climate change, but as the impacts of shifting weather patterns cost more and more, insurance companies are retreating from the markets where they are needed most.

“The market learns,” says Alex Balcombe, a partner at Harris Balcombe, a U.K.-based insurance claims consultancy. He points to the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted supply chains and cost the insurance industry enormously. Afterwards, they stopped covering pandemics. “Insurance companies got their fingers burned massively there, so they’ve learned,” Balcombe says. “You can’t buy insurance for that kind of event anymore.”

Likewise with climate change, insurers are fleeing areas that are prone to floods, hurricanes and wildfires or charging huge sums for coverage. “These extreme weather events are only occurring on an increasing basis, so there’s certainly a market for cover to be provided, but the question is at what premium and at what level?” Balcombe asks.

A big part of the answer, Balcombe says, is parametric insurance, a mechanism that converges with the trend toward increasing specificity for weather events in force majeure provisions, and actually serves to simplify coverage. In essence, parametric insurance ties the payout to the event that causes the loss, not the loss itself, and sets a predefined threshold for payment, so there’s no ambiguity or need to negotiate. For example, a factory or warehouse in a flood-prone area might struggle to obtain traditional coverage, but by setting a specific water level to trigger the payment and installing a sensor to verify, they can proceed with adaptations for minor floods and still get coverage for bigger damages.

“I think parametric insurance is going to become a massive feature, because it’s a much more economic way of doing things, and it gives people certainty,” Balcombe says.

While climate change is dismantling the traditional protections that businesses need, the new solutions are catching up and creating opportunities for companies that are building the post-fossil-fuel economy.

Mark Mann is a Montreal-based journalist and the associate editor at Corporate Knights.