As our societies respond to the climate emergency, calls to “electrify everything” are mounting. Electrifying buildings and transportation and shifts to renewable energy are expected to play a central role in lowering our collective emissions. Yet this expectation comes at a time when the electric power sector has been rocked by several decades of disruption and renewal.

As far back as the 1880s, traditional utility businesses created value by building and operating electric power plants and transmission lines to satisfy the instantaneous demand for power on a 24/7 basis. Technological advances in the 1950s and 1960s led to bigger generators and cheaper power, with single generator units reaching one gigawatt – enough electricity to power 100 million LED light bulbs. And transmission lines operating at 500,000 volts and higher became commonplace. Power utilities achieved high levels of reliability through engineering design and redundancy. They also built business and financing models around the sale of largely undifferentiated kilowatt-hours in a regulated market to captive customers.

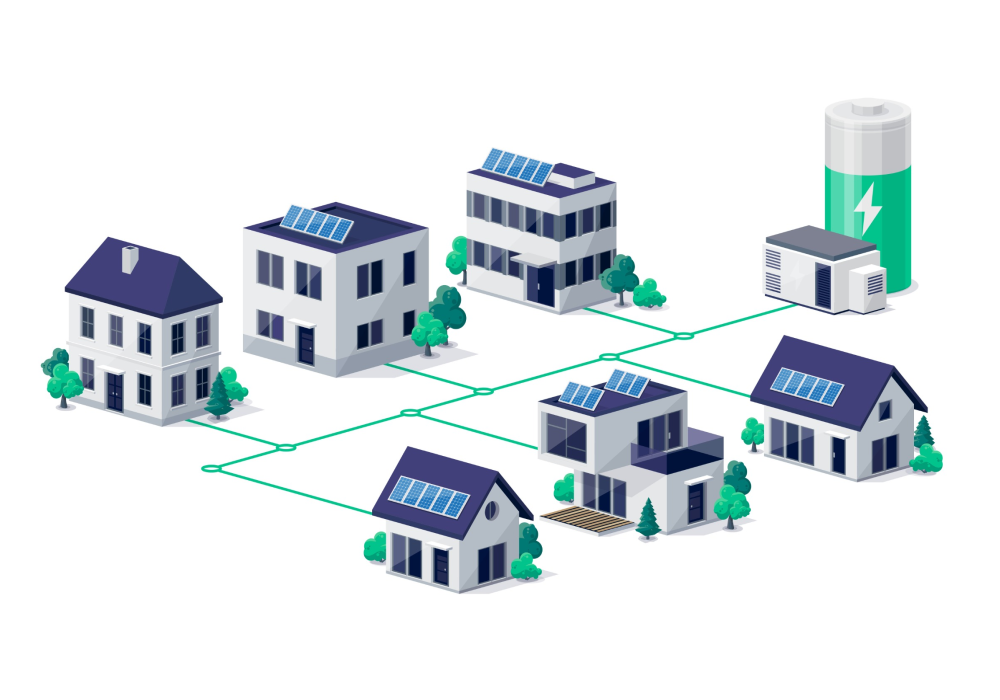

The grid in most neighbourhoods is currently energized with electricity that is brought in on high-voltage transmission lines from large-scale generation assets located either by necessity or by choice in rural or semi-rural areas. In a new call to action, Corporate Knights, members of the Council for Clean Capitalism, and others are urging the federal government to fund neighbourhood-scale “microgrid” pilot projects. These would integrate the technologies, business models and regulatory frameworks needed to decarbonize buildings and transportation, which together account for most greenhouse gas emissions in our cities.

The individual technologies required to achieve this have already been developed and deployed to varying degrees. They include advanced retrofits, heat pumps, battery storage and bidirectional electric vehicle charging, among others. What we urgently need now are demonstrations of how these new technologies can be deployed strategically and cost effectively at a neighbourhood scale. We also need to understand the regulatory barriers they face and how they can be integrated with the established, central grid.

Show me the microgrid

In the emerging system, technological and business model innovations are transforming the way electricity is produced, stored, used and marketed. There is a shift in value creation toward the consumer’s end of the business, and the grid itself is evolving to support the two-way flow of energy and information between producers, consumers and prosumers (those who consume and produce).

It is fertile ground for the new technologies of distributed generation, energy management and energy storage. Relatively short product-development cycles, the commodification of services, the “internet-of-energy,” sophisticated data analytics and mass production of distributed energy resources all challenge status quo business models and regulatory frameworks. Activities and technologies “beyond the meter” and out of reach of the traditional utility modus operandi are proliferating.

Fortunately, all this disruptive change can be aligned with the imperative to decarbonize building heating and transportation. But to fully capture that opportunity will require strategic coordination of business and government at all levels, which is why the Corporate Knights Council for Clean Capitalism is advocating for microgrid demonstration projects on an urgent basis.

The opportunity of microgrids

In 2019, Siemens announced a pilot project in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia in partnership with power utilities. In that project, smart energy consumers (and prosumers) are engaging with utilities to optimize the integration of renewable sources of energy, ensure the stability of the grid and manage decentralized distribution.

It is essential that what we learn from such projects is quickly deployed in other regions across Canada. And we need urgent clarification from governments on the enabling conditions (such as regulations) to ensure the ability to create living labs and test results within 12 to 18 months. If we can get this right, it will help to determine the financial requirements of the energy transition without compromising the reliability and resilience of the grid.

The action needed now

What is needed urgently now are 10 to 15 demonstration projects that will test and prove these effective business models. The required investment is approximately $25 million per project, for a total of around $375 million for 15 demonstration projects. Inclusion of this investment in the forthcoming federal budget will signal the government’s serious intention, and the signatories of this call to action will be there, willing and ready to help.