Duncan Kenyon is the director of corporate engagement with Investors for Paris Compliance (I4PC), with over 20 years of environmental, business and climate-change leadership experience.

The good news is that most of Canada’s big oil companies have pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The bad news is that those pledges fall apart as soon as you look past their initial rhetoric.

On May 4, investors will have an opportunity to ask at least one of the major actors – Enbridge – to adopt a credible net-zero plan in place of the weak one now in place by voting in favour of a shareholder proposal that Investors for Paris Compliance filed.

What constitutes a credible net-zero plan in the energy sector, and how are Canada’s companies falling short? There are several global initiatives, some led by major investors, that dig into the details of such plans to provide guidance, including the Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi), the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC) and the Climate Action 100+ (CA 100+).

There’s some variation across these initiatives, but they have in common some fundamental elements that Canadian oil and gas companies are resisting.

This starts with 2030 emission reduction targets. Climate science tells us that these need to be in the ballpark of halving emissions, and on an absolute basis. But Canadian oil and gas companies have set weak “intensity” targets – reductions per unit of production – that let absolute emissions grow if production grows.

Related to this is another element: what gets measured and included in these targets. Emissions can be categorized into three scopes. Scope 1 are direct emissions from operations, Scope 2 are indirect emissions from suppliers, and Scope 3 are the downstream emissions resulting from your products. Credible plans measure all three and include them in reduction targets, but again Canadian oil and gas companies generally refuse to take responsibility for their Scope 3 emissions, which is the lion’s share.

As always, the most important element is probably “follow the money.” A company can measure its Scope 3 emissions and have robust targets, but if it isn’t aligning its capital expenditures to reach those targets, then they aren’t worth the paper they are written on. Again, look at the planned expenditures of Canada’s major oil and gas companies and you’ll instead find most of the capital headed for new spending on fossil fuel projects, putting the lie to their climate promises.

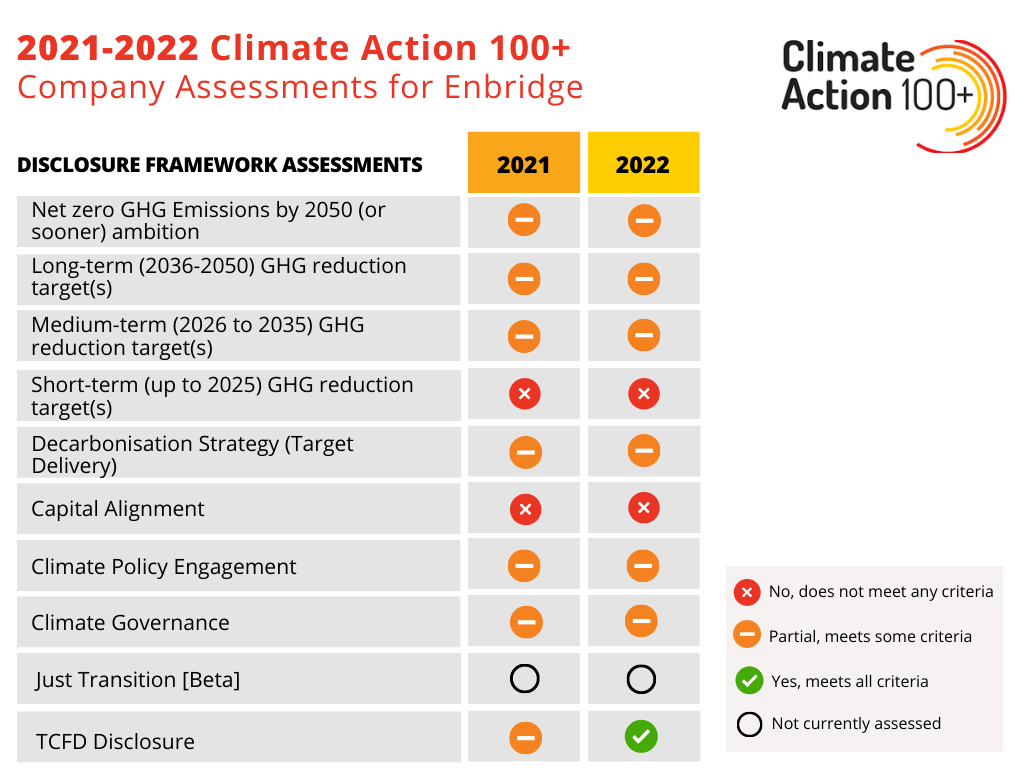

Enbridge is considered one of the more progressive Canadian energy companies but suffers from all of these deficiencies (see chart with CA 100+ assessment from the past two years). It has intensity-based emission reduction targets because it continues to expand its fossil fuel business, meaning that it cannot meet absolute reduction targets so long as it keeps investing in new fossil fuel infrastructure.

Furthermore, Enbridge targets reductions only for its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, leaving out Scope 3 emissions. It does some work to reduce Scope 3 emissions (utility demand-side management or renewable electricity to power its pipelines) but fails to include the other side of the ledger for these emissions. For example, the recent completion of the controversial Line 3 oil sands pipeline expansion resulted in an equivalent Scope 3 emissions impact of 50 new coal-fired power plants.

Finally, looking at Enbridge’s planned capital expenditures, over 80% of its spending is going toward new fossil fuel infrastructure that will lock the company – and the rest of us – into ever greater emissions over several decades.

In some ways, Enbridge is a victim of being a midstream company in an industry where the producers are calling the shots, so we need to deal with the silver bullet that the industry is putting forward to validate its claims to net-zero: carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Again, the claims being made about CCS stretch credibility. It’s an incredibly expensive endeavour that has never been successfully scaled in the way the Canadian oil industry is assuming is possible. The engineering challenges alone are enough to make this a high-risk play, even if the industry is successful in getting the rest of us to fork out tens of billions in subsidies and gets a long-term oil price that makes it economical – again, both doubtful.

But even if all these challenges are solved and CCS is wildly successful, the problem is that it doesn’t deal with Scope 3 emissions – about three-quarters of fossil fuel’s climate impact – that result when the product is burned. Perhaps there are end uses that preclude burning, but that demand for their products isn’t enough to meet the sector’s growth plans.

Add this up and we see why the science behind a true transition to net-zero means starting to take the steps to reduce fossil fuel production. Canadian oil and gas companies must become Canadian energy companies with low- or zero-carbon business lines if they are to successfully adapt to a net-zero world. On May 4, Enbridge shareholders will have an opportunity to send that message to one of the companies we hope makes that transition.