I’ve been fortunate enough to enjoy two high-adrenaline careers as an ER physician and a medical journalist and author. Both careers have come together on my CBC Radio show, White Coat, Black Art, in which I pull back the curtain to explore the culture of health care.

What never ceases to amaze me on the show is the utter devotion of all the health care providers who make up our Canadian health care system. It makes it clear that a sustainable society’s need for competent and passionate health practitioners is as perpetual as the seasons – new generations of high-quality doctors must be encouraged to come out in droves.

And thankfully, they are out there. In my role as radio host, I am often awarded the privilege of hearing from such committed and motivated students embarking on the early years of their medical journey. Recently, Nicole Perkes of Port Coquitlam, B.C., sent me a note announcing her acceptance into medical school, and thanking me for the show’s contribution to her success in making her vision for a future in health care a reality.

In my congratulatory note to Nicole, I reminded her that she did all the work getting past the interview and into medical school—and that she will need a lot of dedication and perseverance to survive her undergraduate years and beyond.

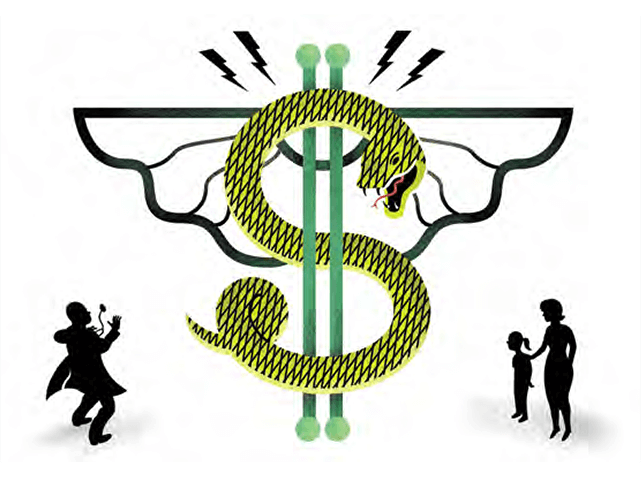

But there is another obstacle in Nicole’s way, lurking in front of all medical students, and whittling away at the numbers of Canada’s future family care providers: debt.

As it turns out, students like Nicole will also need quite a lot of money to graduate. Medical school tuition is rising as though the schools themselves were filled with helium. According to a survey published in Maclean’s magazine last fall, first-year tuition for the previous academic year ranged from a low of $7,499 at the University of Manitoba’s faculty of medicine to a whopping $20,831 at McMaster University. Québec medical schools offer lower tuition costs to Québec residents. University of British Columbia, the school Nicole Perkes enters this September, charged $15,457 tuition to first-year students.

And tuition is only the beginning. Add in books and equipment, plus the cost of living, and the total price becomes daunting.

When I left residency back in the 1980s, I owed the bank $9,700 in student loans. That’s small beer compared to the debt racked up by today’s medical students. According to the 2007 National Physician Survey, more than one-third of respondent students said they expected their medical school-related debts to top out at more than $83,000. Among third- and fourth-year med students, a little more than five per cent said they expected to have total debts of over $160,000.

Yet believe it or not, it could be worse. Three years ago, I travelled to Ireland to visit Geoffrey Stevens, one of several thousand Canadians studying medicine abroad at the time. Stevens, a native of Ontario, attended medical school at Dublin’s Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland. Stevens admitted he didn’t get into a Canadian medical school because he favoured partying over studying during his undergraduate years and his grade-point average suffered as a result. Medical schools in Ireland aggressively recruit students from North America, but at a cost.

At the time, Stevens’ first-year tuition alone cost €34,000. Annual tuition increases, living expenses and the then-weak Canadian dollar drove his total costs to close to half a million Canadian dollars. The debt was always on his mind.

“It influences how my future will unfold,” he said during an interview on White Coat, Black Art. “No matter where I go, I will always be thinking about how to pay this back.”

And why should the dwindling bank account of a medical student matter to you?

Because rising debt doesn’t only affect those budding physicians. It has a huge impact on the health care system itself. According to Statistics Canada, in 2010, 4.4 million Canadians or 15 per cent of the population age 12 and older did not have access to a family doctor. The same survey found that 53 per cent of those without a regular medical doctor had tried unsuccessfully to find one. Among these, 40 per cent said that doctors in their area were not taking new patients, 31 per cent said their own physician had retired, and 27 per cent said there were no physicians available where they lived.

There’s growing evidence that rising medical student debt is playing a role in Canada’s lack of family doctors. Back in 1997, 45 per cent of Canadian medical school graduates chose residencies in family medicine. Since then, there’s been a steady decline. Alain Vanasse, a family physician and a professor of family medicine at the University of Sherbrooke in Québec, and his colleagues analyzed data from the 2007 National Physician Survey and uncovered a disturbing result: Fewer than 31 per cent of medical students choose family medicine. That figure is far below the goal of 45 per cent set nationally and a target of 50 per cent of med school graduates in Québec.

Vanasse and colleagues found that the most important factor driving career course decisions for young doctors is medical school debt. And the heavy financial burdens are swaying more students towards specialty medicine over family care, because there is a better chance they will be able to pay it back. According to the survey, between 54 and 64 per cent of medical students agreed with the statement that if a student has a lot of financial debt, “it is better to choose a specialty as you will make more money and be able to pay off your debt faster.” In fairness, the remainder of students surveyed agreed with the contrary statement: “Choose family medicine as the residency is shorter and you can start paying off your debt faster.”

Either way, like a virus, student debt enters the hearts and minds and the career choices of Canada’s future doctors.

A sustainable society needs family practitioners. Study after study in recent years has concluded that primary care is at the very foundation of good medicine. For one thing, family doctors are more likely to confront a problem at its source, before it even really exists. That’s because they practice the art of prevention before the art of the cure. Your family doctor is aware of your family history, your environment, your personal and financial stresses and your relationships. Their approach to your care is all encompassing.

The orthopedic surgeon who fixes your hip may have excellent technical and diagnostic skills. She may even recommend that you lose a few kilograms before your operation. But it takes a primary care provider like your family doctor to encourage you to eliminate or modify risk factors for diseases like heart attack and stroke in the long run. Family physicians are most likely to encourage a philosophy of prevention, concerned with the entire biological, psychological and social impacts of day-to-day life that might result in illness. Not only that, but you can’t expect a specialist to know your entire medical background the way your family physician does. Historical perspective, especially when it comes to thorough and effective treatment, is not to be underestimated.

Family doctors aren’t just good for the sustainability of patients and society; they’re also good for the system itself. Family physicians deliver timely and detailed care that saves precious health care dollars.

Personally, I think we don’t celebrate primary care enough. As it is, the rate of dissatisfaction among Canadian physicians is high. A 2008 survey by Dr. Joseph Lee, a family physician in Kitchener, Ont., found 42.5 per cent of family physicians have high stress levels, and nearly half of those surveyed said they have high levels of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—the hallmarks of burnout.

The impact of distress among physicians goes deeper, extending into the quality of care we might receive. A survey of nearly 8,000 American surgeons published in the Annals of Surgery in 2010 found that nine per cent of them admitted to making a medical mistake in the operating room. After crunching the data, the authors concluded that the two strongest factors associated with errors were burnout and depression.

And so, the apparent decline in those entering family medicine as a result of rising tuition is troubling. Another point to consider is how many desirable medical school wannabes glance at the cost of tuition and simply take a pass?

I know that medical school is costly. I understand why debt-ridden provincial governments say they can’t shoulder the financial burden of subsidized medical tuition alone. Yet they are being shortsighted if they don’t consider the broader implications of tuition that’s beyond the reach of many of our best and brightest students.

Some provinces are bucking the trend. Last year, Manitoba Premier Greg Selinger announced that medical students in that province would have their tuition fully paid for if they agreed to set up practice in parts of the province that are designated as under-serviced – including Winnipeg’s inner city and parts of rural Manitoba.

Earlier this year, Scott Dobson-Mitchell penned a blog at Maclean’s On Campus with the intriguing title “Should med school be free in Canada?” He asked if taking the financial pain of med school could solve Canada’s health care crisis.

I think it’s an idea worth considering, provided students sign a contract guaranteeing they’ll work in an area that needs physicians. But why stop there? The provinces could consider paying tuition for nurse practitioners (NPs) too. In 2007, the Ontario government announced the creation of 25 NP-led clinics, a new way of delivering primary care in which the NP takes the lead, consulting with family doctors only when their patients require care that falls outside the NP’s scope of practice.

Canada made publicly funded, universally accessible health care a core value of our nation. In doing so, we decided that people of all economic demographics should have access to decent health care. It’s time we made a medical degree accessible to eager students regardless of their ability to pay. All of us have a stake in making sure that bright, passionate students like Nicole Perkes can find their place in the halls of medicine, unfettered by insurmountable student debt.