When it comes to investing for most people, the goal is to make money, not save the world.

Nevertheless, sustainable or responsible investing (whichever term you prefer) has hit the big-time, particularly around the theme of climate change.

Michael Baldinger, head of impact investing at UBS wealth management, which manages more than US$4 trillion in assets, claims that sustainable investing is now the fastest-growing asset class at scale in the world.

It’s hard to argue with the numbers. The Global Sustainable Investment Alliance says there is a US$30 trillion pot of sustainable investments across various themes as of 2018, growing at about 12% per year. A lot of that growth is coming from pension funds and other institutional investors signed up to the UN-backed Principles for Responsible Investment, whose members control US$86 trillion.

Financial markets are driven by two powerful emotions: greed and fear.

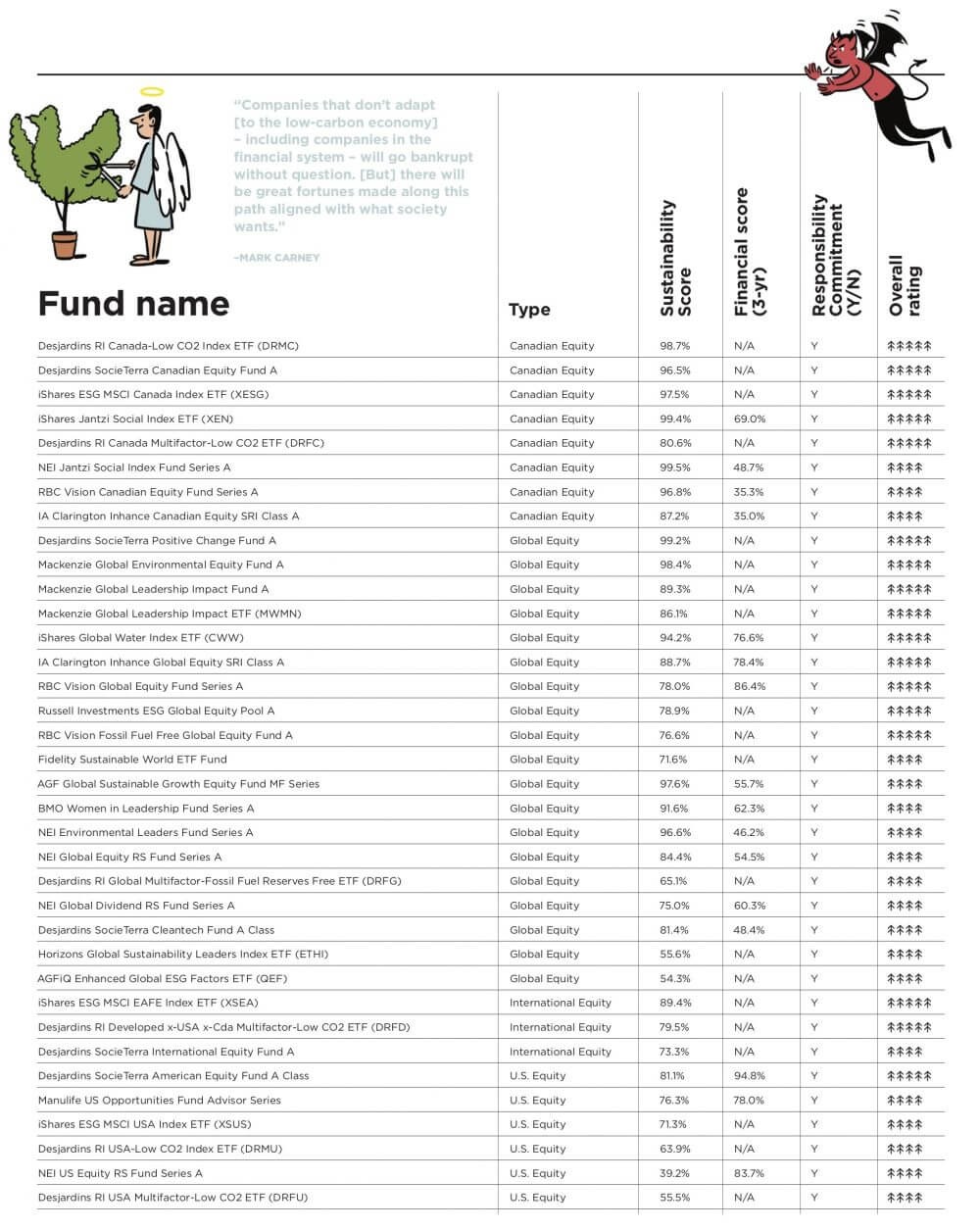

As the outgoing governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, puts it, “Companies that don’t adapt [to the low-carbon economy] – including companies in the financial system – will go bankrupt without question. [But] there will be great fortunes made along this path aligned with what society wants.”

To wit: the top five coal companies in the U.S. have all declared bankruptcy since 2016, and Apple is now bigger than all the oil and gas companies on the S&P 500 combined, in large part because they have earned negative returns over the last decade, even after accounting for dividends.

Carbon-intensive companies are suffering because the alternatives are not just cleaner but cheaper. Renewables are now cheaper than coal in two-thirds of the world’s countries, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance. BNP Paribas estimates that oil needs to come down to US$10 a barrel to be competitive with electricity-driven transport. This does not mean fossil fuels are going away tomorrow, but it does kill the growth story. For oil investors, the market’s realization of this inevitable decline could make the coal horror show look like Bambi.

This increasing speed of the energy transition is part of the reason why investors representing US$11 trillion in assets have made public their plans to divest from fossil fuels.

Perhaps more telling is that beyond these public declarations, many of the biggest investors in the world are selling off their fossil fuel holdings and loading up on green assets. For example, without any fanfare the $200 billion Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan has dialed down its fossil-fuel equity holdings to just 1%. On the upside, the $306 billion Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec (CDPQ) has grown its green investment book to $30 billion, earning commercial returns along the way, according to outgoing chief executive Michael Sabia.

Just in case anyone was in doubt whether sustainable investing is really about making money, the vampire squid of investment banking, Goldman Sachs, showed up this December pledging US$750 billion in financing over the next decade to profit from the climate transition and inclusive growth.

While economics are shifting in favour of sustainable investing, so is public sentiment. Call it the Greta effect if you like, but most people are no longer comfortable with the idea that their retirement investments may be helping to set the world on fire.

Andreas Utermann, chief executive of Allianz Global Investors, which manages US$600 billion, says, “Clients have changed their tune. They have said we need to take this more seriously, and that has sharpened the minds of asset managers.”

Despite all this action among big investors, it appears small investors are getting left behind. If you add up the assets of the 130 funds on offer in Canada that declare sustainability intentions in their official documents, it is less than 1% ($12 billion) of total fund investments ($1.6 trillion). That’s an even smaller fraction than they were at in 2003, when Corporate Knights published its first guide for responsible investors. What gives?

It boils down to a belief many people still hold that sustainable investing is about sacrificing returns. The theory is that investing to make a return is hard enough, and if you add social and environmental considerations into the mix you are at a disadvantage. The trouble with this theory is that investing is like hitting a curveball, which is a pretty good metaphor for the world we live in. Putting on a sustainability lens gives the batter a better sense of the ball’s trajectory and increases the chance of making solid contact.

To make things easier, Corporate Knights scores all the equity mutual funds and ETFs available in Canada according to how well their holdings line up with established sustainability criteria and, where available, their three-year financial performance record. While we’re not promising any home runs, the 36 funds listed below were deemed the worthiest for taking a swing at.

Eco-Fund Methodology

Funds are scored according to (1) three-year net return percentile rank (50%), (2) weighted sustainability rating percentile rank based on analysis of their holdings* (40%), and (3) fund manager intention to manage the fund according to responsible guidelines (10%). If the fund is less than three years old, its final score is based on #2 and #3, which are grossed up proportionately to 100%. Funds that score in the highest or second-highest quintile among category peers receive a five-tree or four-tree rating respectively.

* Holdings that are red-flagged automatically receive a 0% CK Sustainability Rating Score. Red-flag holdings include companies that are classified in the Corporate Knights database for one or more of the following criteria: companies blocking climate policy, farm animal welfare laggards, companies causing severe environmental damage, companies causing deforestation, forced and/or child labour, severe human rights violations, illegal activity, controversial and conventional weapons, civilian firearms, tobacco, thermal coal, for-profit prisons, access to nutrition laggards, access to medicine laggards, digital rights laggards, investor climate laggards and gross corruption violations.

Sources: Corporate Knights Research, Fundata, Responsible Investment Association, Refinitiv, InfluenceMap, Business Benchmark on Farm Animal Welfare (BBFAW), Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), Chain Reaction, Know the Chain, NZ Super Fund, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, American Friends Service Committee, Access to Nutrition Initiative, Access to Medicine Initiative and Ranking Digital Rights.