COPENHAGEN — Denmark seemed the perfect host for the crucial 2009 United Nations climate change summit. The tiny Scandinavian country had a reputation for green living. The Danes were cycling and recycling fanatics. Their streets were spotless, their cars new, their public transportation systems efficient. Electricity prices were outrageously high by North American standards, all the better to encourage conservation.

But Denmark had a dirty little secret that was soon uncovered by the army of foreign journalists at the UN event (I was one of them): It had one of the most carbon-intensive electricity-generation systems in Europe, and the world. And the company largely responsible for the literal black cloud over Denmark – Dong Energy – was controlled by the state. How ironic: The host of the conference whose goal was to lay out a plan to wean the world off fossil fuels was itself utterly shackled to the grubby old world of oil, natural gas and coal.

Dong, which stood for Danish Oil and Natural Gas, emitted fully one-third of the country’s carbon dioxide emissions. Something was indeed rotten in the state of Denmark.

What we journalists couldn’t be bothered to find out at the time was that, by then, Dong and its owners were as repulsed by the company’s black image as the environmentalists were. By 2009, Dong, rather quietly so, was launching a campaign to completely reinvent itself as a top-to-bottom renewable energy company.

“Dong formulated the 85/15 vision,” says Jakob Askou Bøss, the senior vice president of corporate strategy for Ørsted, as Dong has been known since its name change in 2017. “At the time, 85% of our power and heat production was black and 15% was green. Our CEO, Anders Eldrup, said that within a generation, Dong would flip that ratio around, so that 85% would be green and 15% black.”

Eldrup’s definition of “generation” was about 30 years, according to Bøss. In other words, Dong’s reinvention was going to be a slow burn – fossil fuels would darken the company for some time. Instead, the transformation was accomplished more than 20 years faster. By 2018, Ørsted’s green energy output was 75% of total output and the company had reduced its CO2 emissions intensity per kilowatt hour by 72%. By 2025, two years after the last of Ørsted’s coal plants are to be shut, green energy is set to account for 99% of the company’s output while CO2 emissions intensity is to fall by 98% of 2009’s level.

The transformation didn’t end there. In 2009, Ørsted was largely a domestic Danish company. Today, it is the leader in offshore wind power, with control of 30% of the global market. Ørsted has more than two dozen offshore farms in Denmark, Britain, Germany, Netherlands and Taiwan, and has several in development off the U.S. east coast. By 2025, the company says it will generate enough green energy to supply 30 million people, up from 12 million today. The profitable transformation has propelled the company’s stock market value of about US$30 billion, making it one of Europe’s most valuable energy companies.

In January, Corporate Knights named Ørsted as the world’s “most sustainable” energy company and the company’s overhaul has won admirers far and wide. Politicians and energy executives from the United States, Japan, China, France, Poland, India and Taiwan have visited Ørsted’s headquarters, just north of central Copenhagen, to learn how an infamous polluter turned into a global green-energy leader.

“The transformation of Ørsted was really impressive,” says Torben Möger Pedersen, CEO of PensionDanmark, the big labour-market pension fund that has emerged as one of the world’s most aggressive investors in offshore wind projects. “They made the right decision to become a wind-power company.”

The corporate overhaul was not as easy as it appeared. In 2012, just as Dong was spending fortunes on renewable power, it was battered by financial crisis. Even before then, the company was essentially at war with itself as the old guard fought to keep fossil fuels, especially coal, in the energy mix. Among engineers, Dong had a fine reputation as the builder of the world’s most efficient coal plants, and renewable energy alone could not possibly supply Denmark’s energy demands, or so the argument went. But Eldrup, his successor, Henrik Poulsen, and Bøss, who joined the company in 2004 and has been instrumental in Dong’s radical change in direction, were convinced the company could, and would, be painted a pleasing shade of green.

THE TRANSFORMATION of Dong into Ørsted is visible to anyone who lives in Copenhagen. Not only is the sky over the capital city cleaner, but the very symbols of the Dong era are getting a remake.

As you travel north from downtown Copenhagen to the suburb of Gentofte, where Ørsted’s offices are located, you pass the Svanemølle Power Station, facing the Strait of Øresund, which separates Denmark from Sweden. The enormous and oddly handsome, boxy red-brick building, with its distinctive triple white chimneys, was finished in 1953 and burned vast quantities of coal until the mid-1980s, when it cleaned itself up a bit by converting to natural gas.

Today it supplies both electricity and district heating – the system to distribute heat generated as a by-product to homes and businesses – to Copenhagen. But as Ørsted gets out of the fossil fuels game, the idea is to turn the plant into the new home of the Danish Museum of Science and Technology. In some countries, fossil fuel plants are becoming relics of the past, like steam locomotives. But unless thousands more of these plants give up the ghost, the effort agreed at the 2015 Paris climate summit to prevent global warming from exceeding 2 C above pre-industrial levels is doomed.

It was Dong’s desire to bring down Denmark’s embarrassingly high CO2 emissions that triggered the company’s revolution. What Dong didn’t know at the onset of its adventure was that transforming itself into Ørsted – named after Danish physicist Hans Christian Ørsted, who discovered electromagnetism in 1820 – would come with impressive shareholder returns.

Dong was founded in 1972 as a state-owned energy company called Dansk Naturgas. Its mission was to find oil and gas in the Danish sector of the North Sea, whose riches would soon put Britain and Norway on the global energy map (the company was renamed Dong a few years later). At the time, the Danish energy supply was almost entirely based on oil – there was no such thing as offshore wind generation back then – the vast majority of which was imported from Saudi Arabia. Dong’s owners hoped the company’s North Sea production would reduce Denmark’s reliance on Saudi oil. Later, the company would develop a domestic energy transmission network.

Denmark’s reliance on cheap oil was rudely interrupted by the 1974 OPEC oil embargo, which sent prices up 400% virtually overnight. Suddenly, Denmark’s energy bill was crippling and the country moved fast to convert its oil-burning generating plants (none of which was owned by Dong at the time) to coal, which was less expensive and less prone to geopolitical disruption. Coal, the dirtiest fuel, became Denmark’s mainstay.

Over the decades, Dong built up its North Sea oil and gas portfolio. In the middle part of the last decade, it moved into electricity. In 2006, Dong merged with five other domestic electricity companies, two of them producers and the other three distributors, exposing it to coal for the first time. By then, the dangers of global warming had been drilled into the public consciousness. Yet Dong’s strategy, incredibly, was to keep expanding in coal. It was developing the enormous Greifswald coal-fired power station in northeast Germany. “Coal was our core competence,” says Bøss. “We were one of the most coal-intensive energy companies in Europe.”

Not long after the merger, Greifswald became the object of sustained anti-coal protests and by 2008, the year before the Copenhagen climate summit, Dong was having second thoughts not just about Greifswald but about its entire fossil fuel strategy.

“The whole topic of climate change was coming on the agenda,” Bøss says. “Al Gore had published his Inconvenient Truth, which had a big impact, and the EU launched the 2020 [CO2-reduction] goals. At the same time, we were running into resistance at local debates. I can remember talking to our CEO at the time. He said we can invest in offshore wind farms, which will have a bright future and it’s the way society is going, or we can invest in this coal-fired power plant that is fundamentally not the right thing to do. We would be burning coal for 40 to 50 years when we should be converting to green.”

Bøss says “the moment of truth” came in early 2008 when he and Eldrup, the CEO, pretty much committed to the black-to-green transformation. Morally, it was the right strategy and they thought that, financially, they could pull it off, even if the company faced a hefty bill to construct offshore wind farms and dismantle coal plants. The threat of hefty carbon taxes made the transformation all the more alluring. They pushed ahead with their plan without getting a second opinion from outside consultants.

In September of that year, Eldrup used a lengthy op-ed piece in Denmark’s Politiken newspaper to reveal the new strategy to the public. “We must create a completely different energy system, where the majority of the world’s energy comes from the infinite amounts of naturally occurring energy sources, such as wind and sun,” he wrote.

At the same time, he stressed that transformation would not be quick – coal would be around for some time as demands for reliable, cheap energy rose. The message: Dong would clean up its act, but don’t expect an overnight miracle.

What Eldrup didn’t mention is that he and Bøss were facing massive internal pressure to keep Dong as black as possible. To them, the resistance was expected because Dong had spent three decades building itself up as a traditional fossil fuel company. “When you are an oil and gas and coal company and someone comes along and says those are no longer the future, there would be resistance,” Bøss says. “Fossil fuels were seen as our core competence, where we had our growth strategy. Our employees said we are the best in the world in coal-fired power plants – we are the benchmark. There was quite broad and profound skepticism about the plan.”

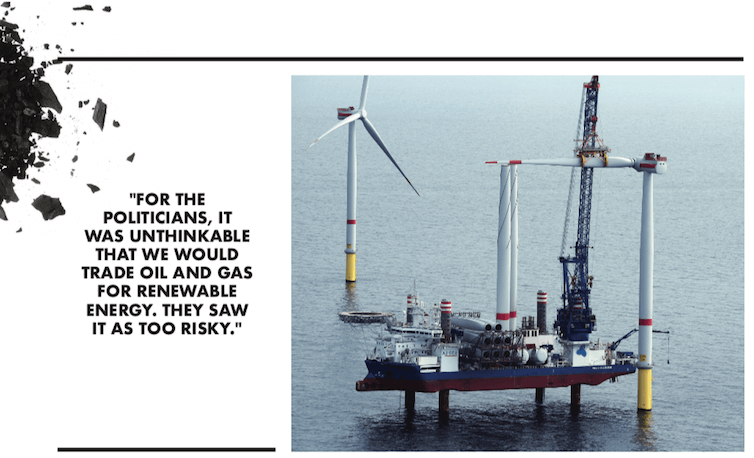

The Danish government was skeptical too, remembers Fritz Schur, the former SAS airline chairman who was chairman of Dong from 2005 to 2014. “Some politicians were afraid that we were investing too little in the secure parts of the company – oil and gas,” he says, noting that even the prime minister requested his presence to explain Dong’s black-to-green strategy. “For the politicians, it was unthinkable that we would trade oil and gas for renewable energy. They saw it as too risky.”

Pedersen, the PensionDanmark boss who watched Dong’s remake and recruited some of its top wind-power executives to start the pension fund’s own renewable energy partnership, says the internal battle came to a head in 2012, when Schur fired Eldrup, the CEO. Pedersen said Schur “disagreed with Eldrup’s plan to turn Dong into a wind-based renewable energy company.”

Bøss disagrees that a clash over strategic visions cost Eldrup his job in 2012. He insists that the dispute instead was over pay, specifically about “unusual compensation terms unknown to him [Schur]” of four senior wind executives who reported to Eldrup. “The board lost confidence in Eldrup,” Bøss says. Schur agrees, saying that whistle blowing over excessive executive pay among the wind executives was behind their ouster (Eldrup could not be reached for comment).

Dong had other things to worry about that year besides rogue executives. The company’s gas business – which included power production, trading, storage and liquefied natural gas – and those of its European gas rivals got slaughtered that year because of plummeting gas prices in the United States. American coal suddenly became less competitive and vast amounts of surplus coal landed in Europe, where it became the preferred fuel for power generation at the expense of gas.

Dong’s enormous gas business lost money in 2012 just as the company’s debt was soaring to pay for the wind rollout.

When Standard & Poor’s downgraded Dong’s debt, the company went into crisis mode which, oddly, accelerated the move into the ever more profitable wind business. To save precious capital, it ditched eight businesses, including all the gas businesses, hydro and the waste-fired power plants. “They were forced to focus,” says Jens Houe Thomsen, senior bond analyst at Denmark’s Jyske Bank. “They had been betting on everything you could bet on. When the crisis came, they put almost everything up for sale and set ambitious targets to take down the cost of producing energy.”

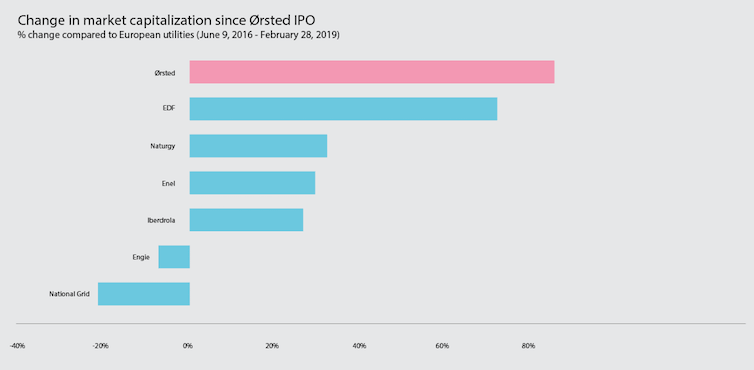

The main survivors were offshore wind and oil and gas. To shore up the balance sheet, Goldman Sachs injected US$1.2 billion into the company, giving it a 17.9% stake (Goldman sold the last of its stake in 2017 for a hefty profit). By 2014, Dong was saved. In 2016, as wind-power earnings were climbing, partly because the technology and installation costs were plummeting, Dong joined the stock market through Denmark’s biggest initial public offering, and the second-biggest IPO worldwide of the year. In 2017, Dong sold its North Sea oil and gas business and changed its name to Ørsted to reflect its near complete transformation from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Ørsted now bills itself as “the greenest energy company in Europe.”

The final proof of Dong’s seemingly miraculous transformation into Ørsted can be measured by its stock market performance. The IPO price was 235 Danish kroner per share. In mid-February, the price was 480 kroner. In the last year alone, the shares have climbed more than 30%. Ørsted has handily outperformed its peer group and the major European stock market indices. Not bad for a company that has evolved into a wind-power utility that was supposed to produce predictable and pedestrian utility returns.

“Denmark can be very proud of what was done at Dong,” says Schur. “It went from having no renewable energy to being one of the biggest renewable energy companies in the world.”

Eric Reguly is the European bureau chief for The Globe and Mail.