There is very little to love about Toronto’s Gardiner Expressway. The six-lane highway that runs 18 kilometres along the shore of Lake Ontario, feeding some 300,000 vehicles into the downtown core every day, is a relic of car-centric postwar urban planning and a symbol of the kind of infrastructural rot that plagues municipalities across Canada.

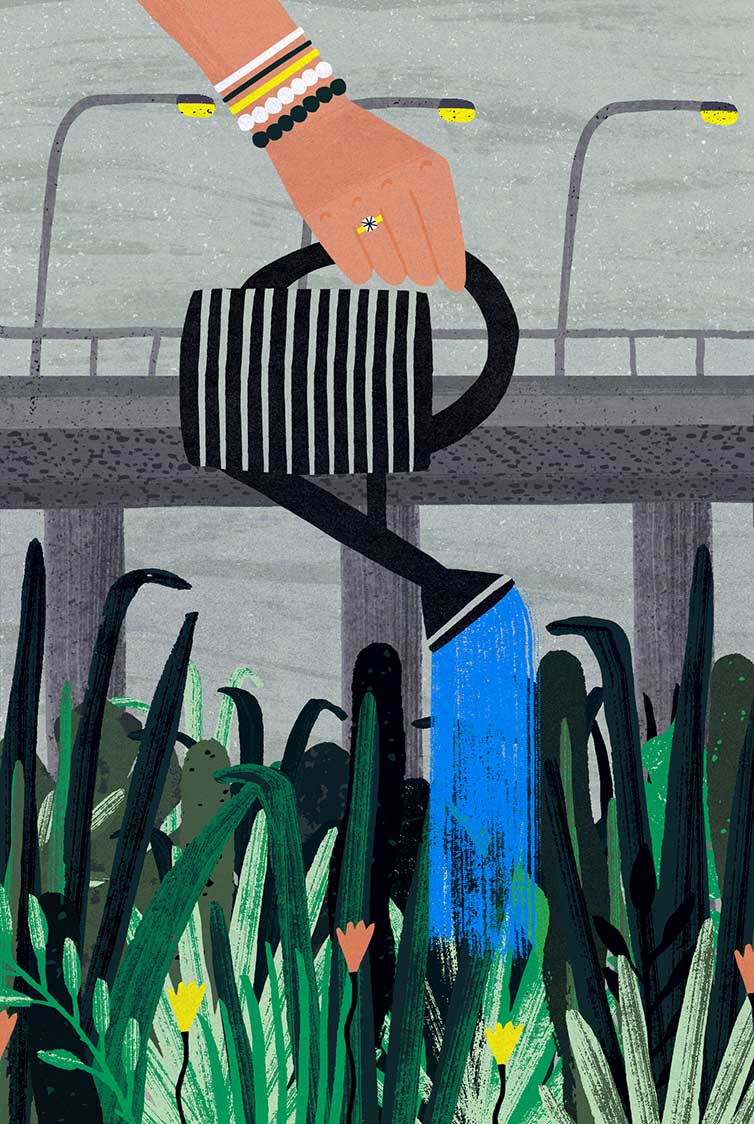

But a couple of well-endowed Torontonians have decided to change that. Last fall, Judy and Wilmot Matthews announced they were donating $25 million to convert the space under the elevated portion of the Gardiner – currently littered with syringes and abandoned shopping carts – into a cutting-edge urban park. In so doing, the couple has shifted the conversation: for years, city council had bickered over whether to rebuild, bury or demolish the concrete beast; now it’s going to be tamed and turned into an attraction.

It’s the kind of counter-intuitive idea that a city struggling to maintain its basic infrastructure would not have hatched on its own. It’s also something of a novelty in Canada, where philanthropy has traditionally extended to cultural institutions, universities and hospitals but not to urban public spaces (the Matthews have previously contributed to several of Toronto’s cultural institutions, a university and downtown park). But with over 80 per cent of Canadians living in urban areas and the country’s municipal infrastructure deficit soaring beyond $123 billion, according to the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, it’s a model whose time may have come.

“This isn’t a frill,” says Ken Greenberg, the Toronto-based architect and urban designer who is design lead of the temporarily named Project: Under Gardiner. “In heterogeneous societies like ours, it’s essential that people meet in public spaces, do stuff together.”

Greenberg had worked with Judy Matthews, a retired city planner, in the city’s planning and development department and they both sit on the board of Park People, a charity that supports community involvement in Toronto’s parks. When she asked him which swath of Toronto could have a “catalytic” impact if converted into interesting public space, he pointed to the 1.75 km stretch under the elevated Gardiner. Crossing two high-density wards whose residents live largely in condos and apartment buildings, Greenberg felt the location would help knit the burgeoning communities together.

Having engaged the local design firm Public Work, they came up with a plan that foresees an urban trail that will incorporate farmer’s markets, dog parks, bike paths, performance and exhibition spaces, playgrounds, and community gardens. Matthews and Greenberg took the plan to Mayor John Tory and the project quickly met council approval.

One condition of the gift was that the city develop a funding model for Under Gardiner’s maintenance and operation in perpetuity. A further criterion was that the project be executed without delay. Its opening is scheduled for the sesquicentennial Canada Day: July 1, 2017.

Everything about the project, from its private sponsorship to the speed of its approval, innovative design, unlikely location and ambitious programming mandate is ground-breaking. Local media were quick to celebrate the generosity and vision of “urban angel” Judy Matthews.

But some onlookers are less enthusiastic. Ray Tomalty, a Montreal-based consultant in urban sustainability and adjunct professor at McGill University’s School of Urban Planning, is having trouble reconciling the design renderings with the extant reality. He says the location, which he calls “a hellish sacrifice zone,” is fundamentally unsuited to leisure and recreation and he bristles at comparisons to New York’s High Line, a linear park that runs the course of an abandoned elevated freight rail: “open to the sky, surrounded by historic districts and on infrastructure that is no longer in use.”

“A family playspace under a busy elevated highway?” he asks of the Under Gardiner project. “I’ll eat my hat if it works.”

More broadly, Tomalty is concerned about donors imposing their “quixotic” visions on cities left to maintain unwieldy, costly spaces. While not programmatically opposed to private funding of public space and acknowledging that public-private partnerships can be a helpful part of the political landscape, he worries when the city has “no leverage.” He’s convinced that Under Gardiner would have been turned down had it undergone the public sector approval process. He also feels that the forces behind the Gardiner gift have been “talking out of both sides of their mouths,” inviting public involvement in the project, while at the same time presenting the plans as a fait accompli.

Urban planners make a distinction between “place-making” and “place-keeping” and Tomalty feels that private engagement is most effective at the latter: programming and operating public space but not creating it in the first place. He cites the Central Park Conservancy in New York City and the Bow to Bluff Initiative in Calgary as two prime examples of citizen groups greatly enhancing existing green spaces.

Another issue lurking in the urban philanthropy model is that of equity. Philanthropists typically invest in projects that benefit themselves or their kind; deep-pocketed Manhattanites formed the Central Park Conservancy, which raises 75 per cent of the park’s annual budget, because it’s their back yard. And while the Gardiner gift does not follow in this tradition – Matthews seems to be genuinely interested in supporting the commons – there is a concern that as funding of public space shifts more into private hands, certain kinds of neighbourhoods may be left behind.

Jeff Biggar, PhD candidate in urban planning at the University of Toronto, sees a large and growing divide between public spaces in the downtown core and the city’s outskirts. With private developers compelled to invest in local community spaces and projects, the less booming parts of the city are falling behind.

“The suburbs may be green,” says Biggar, “but you won’t find much attention to urban design. It’s not just about space, but quality of space.”

Sabina Ali lives in a neighbourhood that might fall prey to this kind of neglect, were it not for engaged citizens like herself. In 2008, she moved from Saudi Arabia into immigrant-rich Thorncliffe Park, a tower neighbourhood designed in the 1970s to accommodate 12,000 residents and now home to over 30,000. A mother of four, Ali soon realized that the local park was stretched thin: “Kids lining up for swings, garbage everywhere.” Together with some like-minded women, she formed a committee that has turned the park into a lively focal point for the community. They started a weekly South Asian-style market, fundraised for a tandoori oven, successfully lobbied the city for a new playground, splash pad and community garden, and secured a sizable private grant to bring environmental education programs into a local ravine.

She was honoured to be invited to sit on the jury to choose a name for the Under Gardiner project (a winner will be announced in July) and very impressed by the nearly 900 proposals submitted by Torontonians of all ages and stripes. Not worried that the project will only serve a downtown crowd, she’s quite certain that members of her community will make use of it, even if it’s just en route to other destinations, like the lakeshore and islands.

“Toronto is a huge city, you can’t get everyone involved in everything,” she says, “but public space is always a good thing. It makes life in the city livable.”

The overarching question hovering over private investment in public infrastructure is whether it lets governments off the hook. Mike Layton, city councillor for one of the two wards that Under Gardiner will traverse, says, “We’re very grateful for this significant gift but are under no illusions that we’re going to build a better city through philanthropy alone.”

Layton is adamant that Toronto is currently “running too lean” and needs to invest more in its public spaces and infrastructure. The most obvious lever is property taxes, which in Toronto’s case are well below the average of the Greater Toronto Area. Layton is discouraged that even as council widely acknowledges “we need better parks,” it continues to resist the necessary tax hike to make it happen. The success of private sector involvement, he says, depends on strong complementary public funding.

It’s a classic Canadian position, notes urban designer Greenberg, a New Yorker by birth who has worked extensively in the U.S. as well as Canada.

“The U.S. has given up on government,” he says, opposing this to Canada’s unshakable faith in “peace, order and good government.” Greenberg would not want urban philanthropy in Canada to become an excuse for governments to exit stage left. But his experience south of the border suggests that the kinds of projects that philanthropists get behind are ones that otherwise would not happen – often avant-garde, outside-the-box ideas that are beyond the scope of the public purse.

Greenberg is optimistic that the Gardiner gift will focus an ongoing discussion about blended funding models and provide a blueprint for projects that combine municipal with private funding – of which he is convinced there will be ever more.

There’s a certain amount of hubris associated with city-building. “When this is built, it’s going to be built forever,” Fred Gardiner told his five-man Metropolitan Executive committee in July 1953 as it cringed at the $35 million price tag for the expressway that would bear his name.

Under Gardiner is making no such claims. Matthews doesn’t want her name plastered on it and the project’s website describes it as an open-ended “stretch of possibility”. Time will tell what Toronto makes of it.