In much of North America, if you want to buy an electric vehicle, you’re going to shell out far more than if you lived elsewhere.

In China, you can purchase the compact BYD Seagull for ¥90,000, or about $17,000 Canadian. In Switzerland, the similarly sized Dongfeng Nammi Box runs about $27,000. But in the U.S. and Canada, the cheapest EV is the three-door hatchback Fiat 500e, which comes in at $40,000. That’s a 48% surcharge for living in the wrong country. Or, more precisely, for keeping cheap, Chinese-built EVs out.

There was some hope that cheaper EVs were on their way, but that was extinguished this summer when Washington and Ottawa announced 100% tariffs on Chinese EVs, essentially guaranteeing they will not be available anytime soon.

Support for this decision has been nearly universal – from industry, unions and partisans across the political spectrum, who say it will protect a nascent domestic EV supply chain, which has been promised more than $50 billion in public subsidies in Canada (and nearly 10 times that in the United States) and all the jobs and economic ripple effects the auto industry provides. North America’s auto industry, it appears, is simply too big to fail.

Just as the integrated auto industry benefited from massive Canadian and American bailouts during the financial crisis 15 years ago, these tariffs can be thought of as a preemptive bailout, a tacit admission that local producers cannot compete with Chinese automakers, which both governments say have the unfair advantage of cheap labour and government subsidies.

Only this time, the bailout is being paid for by the consumer – who will shell out tens of thousands of dollars more for an EV – and the climate, which will be forced to absorb additional carbon due to the slower uptake of more expensive EVs.

We can’t lose sight of the fact that getting affordable electric cars into people’s hands isn’t something that is optional. It is essential to achieving our climate goals.

— Nate Wallace, clean-transportation program manager at Environmental Defence

The opportunity cost of keeping out Chinese EVs

If inexpensive Chinese EVs were available in Canada, they would supercharge EV adoption, adding an estimated 1.8 million zero-emission EVs to our roads over the next decade and lowering our carbon emissions by almost 28 million tonnes. These ultra-low-cost EVs would also free up more than $5.3 billion in family budgets – money that will now be spent on more expensive EVs, gas cars and gasoline instead.

These numbers, crunched by Corporate Knights’ director of research Ralph Torrie and shared with the Toronto Star, show the opportunity cost of keeping Chinese EVs out of Canada, all in the name of protecting the local auto manufacturing industry. The figures demonstrate how tariffs will imperil our climate targets, drive inflation and dampen economic growth by eating up billions in disposable income, Torrie says.

Former U.S. president Donald Trump has said that the tariffs are a “tax on a foreign country” and will, in effect, make China pay for “ripping us off and stealing our jobs.”

Economists across the political spectrum, however, say that tariffs will actually drive prices up – in other words, stoke inflation. “We didn’t go to Trump University, thinking that China will pay these tariffs,” says Nate Wallace, clean-transportation program manager at Environmental Defence. “They’re a tax on Canadian consumers with the explicit intent of raising prices.”

Meanwhile, trade with China in other goods is booming, reaching more than $100 billion last year. Tariffs on EVs only single out a particularly essential climate-change-fighting technology for punishment.

“There will be fewer EVs and more emissions,” Wallace says.

What’s worse, the tariffs could end up failing to achieve their goal of fostering a local EV industry. Some who have seen Chinese EVs up close – including the CEO of Ford Motor – say they are so advanced and so cheap, legacy automakers might never catch up. In other words, Chinese EVs are on track to dominate globally, and these tariffs could end up doing nothing but forestalling the inevitable.

The number one barrier to EV adoption: sticker price

In the United States, EVs have become the focal point of culture wars around climate change. But in Canada they had the magic power to bring erstwhile opponents together, with environmentalists and business leaders, Liberals and Conservatives, unions and management working to encourage the development of a domestic EV supply chain to reduce carbon emissions and provide a new generation of blue-collar jobs.

The tariffs, however, shattered this alliance, definitively putting economic development ahead of emission reductions.

“We can’t lose sight of the fact that getting affordable electric cars into people’s hands isn’t something that is optional. It is essential to achieving our climate goals,” Wallace wrote in a submission to the Canadian government calling for lower tariffs.

Road transportation is responsible for 17% of carbon emissions in Canada and 22% in the U.S. Globally, thanks to EVs, the transportation sector is one of the few that’s on track to reach net-zero by 2050. But North America lags behind.

If Americans or Canadians are ever given the opportunity to buy these vehicles, I think they would sell a lot stronger than a lot of Western automakers would think – and I think that’s really terrifying for them.

— Kevin Williams, reporter for InsideEVs

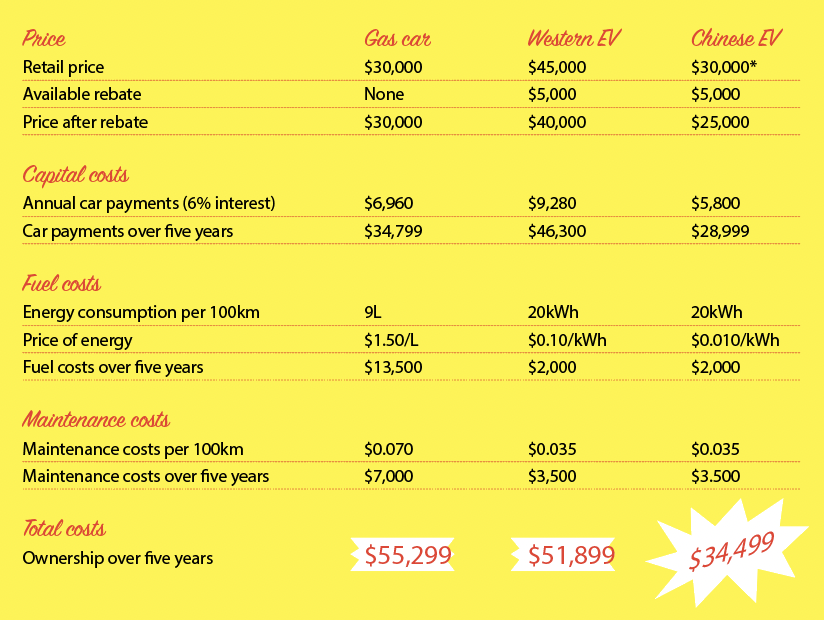

The number one barrier to EV adoption is sticker price. Despite many studies showing that the overall cost of owning an EV is cheaper in the long run than a gasoline-powered car, they remain significantly more expensive upfront in the North American market.

In China, however, EVs have achieved price parity with cars powered by internal combustion engines across price points – from the cheapest models to the most luxurious – and the results speak for themselves: China leads the world in EV sales, with more than one-third of all new cars powered by batteries. In fact, more than 60% of all EVs bought globally are purchased in China.

For mass adoption to take off in Canada, EV prices would have to drop by one-third to one-half, according to a Scotiabank analysis released last year. This is also how much cheaper Chinese EVs are today. Yet EVs in North America are only getting more expensive. The two cheapest models on the market – the Chevy Bolt and Nissan Leaf – were recently discontinued.

“The only reason why low-priced electric vehicles from China pose any kind of threat to this industry is because the legacy automakers in North America have so far refused to bring affordable electric vehicle models to market,” Wallace wrote.

Tim Burrows, president of the EV Society, a Canadian non-profit that promotes EVs as a climate solution, says the tariffs on Chinese EVs appear at first glance to be jumping the gun. “There are no vehicles that it’s going on in Canada,” he says. “We don’t have Chinese EVs, and we have no EV industry to protect yet.”

Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of Canada and now the UN’s special envoy for climate action and finance, has questioned the lavish U.S. and Canadian subsidies to the auto industry to spur EV manufacturing, saying the money would be much better spent subsidizing heat pumps for households that can’t afford them.

But Burrows sees how tariffs are necessary to prevent cheap Chinese EVs from flooding the market. Our auto industry, he says, needs time to catch up: “The Chinese didn’t just show up with cheap, well-made EVs. They started 15 years ago. We’re just starting out.”

Burrows and other EV advocates take issue with the lack of a sunset clause in the tariffs. If they were in place for a limited time – say, two to five years – with a clear end date, the tariffs would allow enough time to develop a North American supply chain and bring more inexpensive models to market. But as things stand now, they say that the tariffs coddle the domestic auto industry, which hasn’t shown any urgency in offering more EVs for sale.

Or, as Wallace puts it: “No accountability mechanisms exist to apply downward pressure on EV prices, whether it be regulatory requirements or market-based competition.”

Chinese vehicles kick their bad reputation

Because Chinese car brands aren’t available in Canada and the United States, few people can say with authority whether they’re any good, or if they’d sell. Kevin Williams is one of those people. An Ohio-based reporter with InsideEVs, he travelled to Beijing to test-drive Chinese EVs and says they’re so good, Western automakers are “cooked.”

“Chinese EVs are competitive in ways that go beyond just price,” he says. “They’re stylish, they’re well-made, and they work really well.” Williams, who has not minced his words after test-drives of lacklustre American EVs, says Chinese vehicles have bucked their reputation for inferior quality. “For a long time, Chinese cars really weren’t great,” he says. “That isn’t true anymore.”

In the early 2000s, a lot of Chinese cars were simply cloned versions of Western cars that had been reverse engineered. Then in the late 2000s, automakers in China pivoted to EVs – or “new energy vehicles,” as they’re called there – and invested far more in their development. Now, 15 years later, Chinese manufacturers sell more EVs than all other car companies combined.

RELATED:

Can Quebec turn its green battery dreams into a reality?

Low-cost EVs on ‘verge of extinction’ as Canada slaps 100% tariff on Chinese cars

U.S. voters are all in on climate policy – even if they don’t know it

“They’ve been doing a lot of research and development and refining their product to the point where now they’re one of the biggest automakers in the world,” Williams says. “It didn’t happen in a vacuum. They didn’t just all of a sudden start making solid vehicles. It took a minute.”

Detroit-area company Caresoft, which takes apart cars to analyze how they’re built, tore down a BYD Seagull and was impressed with the quality of its construction, especially for the price point. The company was similarly impressed with other Chinese EVs and wrote that “the automotive landscape is set for a significant shift, driven by the rapid evolution of China’s electric vehicle industry [which] should serve as a wake-up call to legacy automakers.”

Williams says that if they were available in Canada and the U.S., there’s no doubt Chinese EVs would find eager buyers. “Most consumers don’t care where the product comes from,” he says. “If Americans or Canadians are ever given the opportunity to buy these vehicles, I think they would sell a lot stronger than a lot of Western automakers would think – and I think that’s really terrifying for them.”

In the 1980s, Japanese cars were cheaper and better than North American options and were being snapped up at a rapid clip. Then-U.S. president Ronald Reagan imposed Japanese import quotas to allow the domestic auto industry time to catch up, and four years later, after Japanese companies agreed to open factories in North America, the quotas were dropped.

Now, Japanese cars are ubiquitous. And North American cars still exist – and they’re vastly more reliable than they were before competition arrived.

Throughout history, the greatest automotive innovations have been a result, oftentimes, of the government challenging automakers to improve.

— David Tracy, editor-in-chief of The Autopian

All EV supply chains lead back to China

One of the only places on earth where Chinese EVs can compete head-to-head with Western vehicles is Australia, which has a free trade agreement with China. In Australia, Chinese-built EVs now control 80% of the EV market, and Chinese brands are the most popular, behind only Tesla.

John Cadogan, a veteran Australian automotive journalist and qualified mechanical engineer, is far less enthusiastic about Chinese EVs, calling them “a functional appliance.” He says they’re good for people who can’t afford more expensive models but can’t compete on quality. “When you make anything cheaply, inevitably quality issues such as endurability and performance suffer,” he says. “Consumers are finding that out.”

But the line between Chinese EVs and others isn’t as clear as you might think. Regardless of where they’re assembled, all EVs rely on numerous parts from China. From semiconductors to battery cathodes, even the raw minerals in batteries and the rare earths in electric motors, all cars – and especially EVs – are reliant on a supply chain controlled by China. “It’s becoming very hard to differentiate what’s Chinese-made and what’s not,” Cadogan says.

As a result, as soon as EVs start rolling off the line in the U.S. and Canada, they’ll still be drawing from the Chinese supply chain, and that won’t change until new mines and refineries are up and running, a process that typically takes more than a decade.

A missed opportunity to expand the power grid

With tariffs in place, and few used EV options on the market, budget-conscious Canadians will be pushed back into the internal combustion engine market. This means another eight years on average of paying private-sector oil companies to fuel up rather than (mostly) publicly owned utilities.

According to Corporate Knights analysis, utilities would receive $3.5 billion in additional revenue over the next decade from the charging of Chinese EVs alone – badly needed funds that could be used to expand the grid to support electrification of the economy.

Without Chinese EVs providing inexpensive options, EV sales aren’t growing fast enough to meet the federal government’s legislated 60% target by 2030 and 100% by 2035. Estimates put out by the Parliamentary Budget Office show that EV prices would need to drop by one-third to meet the first target.

Coincidentally, the cheapest Chinese EVs retail in Europe for about one-third less than the cheapest EVs available in Canada. And while the 100% tariff in the U.S. and Canada leaves no room for negotiation or improvement, the EU’s 38% tariff has already been dialled back on several models, following an investigation into state subsidies.

Being more open to addressing specific grievances with Chinese EVs could create an incentive for China to improve its labour and environmental practices while increasing access to cheaper EVs in Canada. In France, for example, EV rebates are dependent on the car’s carbon footprint – only vehicles made with clean energy qualify.

Are the government and industry up to the challenge?

On the other hand, dropping the tariffs entirely and allowing Chinese EVs to flood the market isn’t a great option either. It would not only cede a critical industry to a geopolitical rival; it would mean looking the other way on the objectionable labour practices and underregulated pollution the Chinese EV supply chain relies on.

Instead, government regulations – that is, limiting rebates on expensive EVs – could be necessary to drive down prices, says David Tracy, an automotive engineer and editor-in-chief of The Autopian, a car-focused online publication.

In the past, when the market has failed to protect consumers and the environment, the government has stepped up to make a difference, he says. “I’m all about competition. But as someone who is well versed in automotive history, I’ve seen how really challenging automakers has led to great things. Throughout history, the greatest automotive innovations have been a result, oftentimes, of the government challenging automakers to improve,” he says.

Fuel economy regulations in the U.S, for example, yielded cars that are more powerful, more reliable and more efficient than ever. “And that doesn’t happen naturally,” Tracy says. “I think if we just went by the market, it’s possible we’d still have carbureted automobiles without airbags.”

Marco Chown Oved writes about climate change for the Toronto Star. With files from Ralph Torrie, director of research at Corporate Knights.

This story is jointly published with the Toronto Star.