As more people become concerned by the heat waves, forest fires and flooding exacerbated by climate change, they’re switching their carbon-emitting home appliances for electric, emissions-free alternatives. The impact of millions of electric vehicles, heat pumps, induction stoves and heat pump water heaters can be measured not only in carbon emission reductions, but in significant savings too.

Corporate Knights partnered with the Toronto Star to analyze the co-benefits of these clean technologies, quantifying just how much households can save by adopting them, and what their impact will be on emissions.

If someone had told you in 2008 – the year after the first iPhone was released – that in the next 15 years, virtually everyone in Canada would have a smartphone, you might have rolled your eyes all the way to the internet café (as you slowly tapped out a text on your numbered keypad).

Nowadays, it’s hard to believe we ever lived without the internet in our pockets. But that’s how adoption curves work: new technology is adopted slowly at first, then all at once.

The digital technology that swept our lives into this millennium changed the way we communicate and shop, plan trips and watch shows. But it also came with a heavy cost to the planet. The greenhouse gases produced by online video streaming exceed 1% of global emissions. Bitcoin miners produce more carbon emissions than all of Serbia.

The next wave of technological upgrades to our lives, however, will emit zero carbon. It’s going to change how we get around, the way we heat and cool our homes, and what we use to cook and take showers. The electric vehicle, heat pump, induction stove and heat-pump water heater may not alter our behaviour so much as texting and email. But they will revolutionize society, allowing us to continue to do many daily activities – only faster, more efficiently and without producing any emissions.

And they are poised to go from curiosity to ubiquity more quickly than you think.

Their carbon-saving potential is enormous. According to an analysis by Corporate Knights’ research division and shared with the Toronto Star, these four technologies alone would cut the average Canadian household’s carbon footprint by 80%. If everyone made the switch, it would eliminate 92 megatonnes from Canada’s national emissions annually – more than the entire oil sands produces.

The financial benefit is even greater. If everyone in Canada swapped out their existing gas-powered car, furnace, stove and water heater for these green technologies, the collective yearly savings would be more than $65 billion, the analysis found. That’s $4,300 per household.

If everyone in Canada swapped out their existing gas-powered car, furnace, stove and water heater for these green technologies, the collective yearly savings would be more than $65 billion and 92 megatonnes of CO2 – more than the entire oil sands.

These ecological and economic incentives have created the conditions for rapid adoption, motivating governments that have emission-reduction targets to meet and individuals feeling the squeeze of fossil-fuel-driven inflation.

Critics say fear of climate change will not prompt people to adopt new technology. They argue that we just love our gas stoves and gas-guzzling SUVs too much. But dozens of car dealers and HVAC professionals who spoke with the Star said EVs and heat pumps are popular not because they’re green – people are buying them for other reasons: convenience, comfort and cost savings. The end result is a win-win. People’s lives get better. They save money. And the faster these technologies are adopted, the fewer emissions Canada will produce.

Corporate Knights partnered with the Toronto Star to analyze the co-benefits of these clean technologies, quantifying just how much Canadians in each province can save by adopting them, and what their impact will be on emissions. The results vary widely across the country.

In Quebec, Manitoba and British Columbia, where hydro dams provide cheap, carbon-free electricity, the benefit of ditching fossil fuels is the greatest. An average British Columbian household switching to these four technologies would save more than $4,800 per year and virtually eliminate their carbon footprint (83% average).

In provinces with carbon-intensive electricity, such as Alberta and Nova Scotia, switching off fossil fuels has a smaller impact – and can even make your emissions rise in some cases – but the financial benefits are not insignificant. An average Nova Scotian household adopting the four green technologies would save $5,200 per year and shrink their emissions by five tonnes (or 64%).

Switching now is also future-proofed. As the carbon tax rises, the cost savings grow – reaching an additional $790 per year on average* for every Canadian household in 2030. And as the electrical grids in these provinces decarbonize, the already low emissions will piggyback them right down to zero.

In the U.S., those figures will shift state-to-state as well. But in New York, households switching to these four technologies would save an average of US$2,133 per year while reducing their carbon footprints by 7.3 tonnes.

We’ve reached out to early adopters in Canada to find out about the benefits and challenges of these technologies and have created online calculators so you can figure out the estimated cost and emissions savings associated with each technology depending on where you live. While no one would say these four pieces of green technology are a panacea for solving climate change, they’re a big start. And they’re something individuals can do without waiting for the government to act (though the incentives and rebates help).

Each EV, water heater, heat pump and induction stove on its own may not make a big difference for the warming planet, but they will save a family hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars a year. And as North Americans switch away from burning fossil fuels and electrify their lives, the cumulative power of individual action is undeniable.

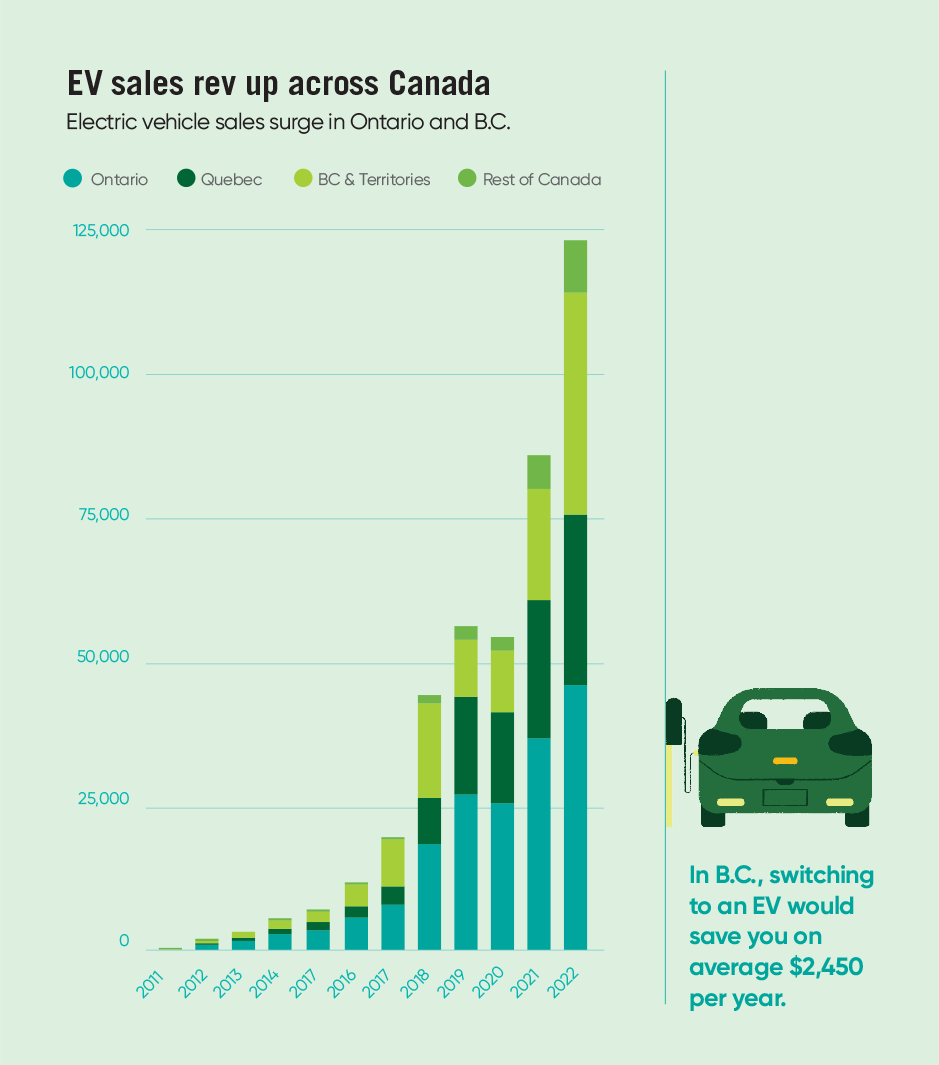

Savings from switching to an electric vehicles

David Hollingworth is an active skier, someone who heads up to Whistler from his home in North Vancouver for a day on the slopes whenever the powder is fresh. But unlike many of his neighbours, he straps his skis to the top of his EV – a Nissan Leaf – for the trip into the mountains and leaves his family’s gas-powered car – a Honda CRV – at home. “It’s just a no-brainer, the cost savings,” he says. While it costs more than $100 to gas up the CRV, Hollingaworth estimates that an overnight charge for the Leaf runs him only about $2.

In the eight years since he bought his EV, Hollingworth says, he’s grown more enamoured with it. The electric car serves his family’s day-to-day needs so well they’ve cancelled the insurance on their gas-powered car except for a few months in the winter when they go on longer ski trips.

“I don’t keep a log of the expenses for both vehicles, but it’s just obvious. I’m sure that we’ve saved thousands of dollars in fuel and maintenance [with the EV],” he says. “Even driving the CRV a lot less, it seems to cost us at least $1,000 in repairs every year. And the Nissan Leaf, it’s basically maintenance-free.” Fuel and maintenance savings are often cited as the top benefits by EV owners. In B.C. – which has the highest gasoline prices in the country and some of the lowest electricity prices – those savings are $2,450 per year on average, according to the Corporate Knights analysis.

The savings assume charging at home using average electricity prices. Of course, many EV owners minimize their costs by charging overnight when electricity is cheaper and searching out free charging, still widely available.

While EVs have a reputation for being expensive, this is changing quickly. Many of the early high-end models are now making way for entry-level EVs priced far lower than the average cost of a new car in Canada, which hit $58,478 at the end of last year.

A survey of Toronto car dealerships last year turned up four EV models with a listing price below $40,000 and nine more between $40,000 and $45,000. These prices don’t include the $5,000 federal EV purchase subsidy, which is topped up by certain provinces, ranging from $2,500 in Newfoundland and Labrador to $7,000 in Quebec. (Ontario cancelled its EV purchase rebate in 2018 when Doug Ford’s Progressive Conservatives came into power.)

In B.C. and Quebec, the purchase subsidies are coupled with a sales mandate, requiring dealerships to have EVs available for purchase. (The federal government announced a nationwide sales mandate last December.) This combination has fuelled the fastest uptake of EVs in the country. Last year, EVs made up 16% of all new car sales in B.C. and 12% in Quebec.

Ontario lags behind. Only 6.5% of new car sales in the province were EVs last year. Since automakers send their EVs to the provinces that have sales mandates, Ontarians have to wait for months or even years on Canada’s longest EV wait lists.

In addition to savings, EVs also boast souped-up climate impacts. Even in provinces with electricity generated from fossil fuels, EVs dramatically reduce emissions because they’re so efficient. In an EV, up to 91% of the energy in the battery goes directly to turning the wheels, while in a gas-powered car, 84% of the energy in the gas tank is lost to heat and friction.

So in Alberta and Saskatchewan, where most electricity is generated by burning coal and natural gas, an average family would reduce their carbon emissions by 1.2 tonnes by switching to an EV, the Corporate Knights analysis found.

In Quebec, Manitoba and B.C., where most electricity comes from hydro dams, an EV would reduce a family’s carbon emissions by far more: 3.1 tonnes per year.

Nationwide, if everyone switched to an EV, it would reduce Canada’s carbon emissions by 57.8 megatonnes, or about 8.6% of all emissions. This assumes we maintain our current electrical generation sources. But if the federal government succeeds in getting our electrical grids to net-zero by 2035, EV adoption would reduce emissions by 67 megatonnes, or 10%.

On each trip up to Whistler in his Leaf, Hollingworth has to make a 20-minute stop in Squamish for a quick charge. He uses the opportunity to stretch and admire the mountains, taking pleasure, he says, in knowing he’s doing his part to protect them from climate change. “There is some type of endorphin or dopamine that happens when you know you just saved a bunch of carbon emissions.”

He says he thinks everyone will soon be driving EVs, not only to reduce emissions, but because they’re so much cheaper and more convenient to operate. “We’re in a transition period now. People will roll their eyes in the future when they look at how we lived today.”

Savings from switching to an electric heat pump

Shortly after Brian Gifford retired and moved back to Halifax, he knew he had to do something about the oil furnace in his basement, which was costing him $2,500 to run each winter. Not knowing that he had any choice but to continue to use oil, he added insulation to his basement, walls and attic – and saw his heating bills go down to $1,700.

Five years later, he was told his firebox had a crack and the furnace would have to be replaced, so he looked at switching to natural gas – newly available in the Maritimes – or buying an electric heat pump. “Both environmentally and financially, heat pumps made a whole lot more sense,” he says. Installed in 2015, the heat pump has reduced his annual heating bill to $700 – about a quarter of what it used to be. “The heat pump is a huge, huge benefit, especially in places like the Maritimes, where heating costs are relatively high because we use oil,” he says. “We’re saving a lot of money. We’re really happy with that.”

For decades, heat pumps weren’t powerful enough to heat through Canadian winters. But a new generation of cold-climate heat pumps now available have been shown to work in the deep cold of Whitehorse. They also do double duty, running in reverse to provide air conditioning in the summer.

Much like the EV, the heat pump electrifies something that’s traditionally powered with fossil fuels. And like an EV, switching to a heat pump to heat your home saves money and reduces emissions – even on a dirty grid, like Nova Scotia’s – because the technology is so much more efficient.

*Because the electrical grid is so carbon-intensive in Alberta, there are no emissions savings from electrifying heat/ water heating/ cooking at the current time. But the grid is decarbonizing quickly, and this will soon no longer be the case.

While the newest natural gas furnaces operate at 98% efficiency, heat pumps are 220 to 320% efficient in Canadian conditions. This means that in a furnace, one unit of energy in natural gas produces 0.98 units of heat in your home. But with a heat pump, one unit of energy in electricity produces 2.2 to 3.2 units of heat. This works because heat pumps use ambient heat in the air and concentrate it, gaining a multiplier effect on the energy used to power the process.

As a result, heat pumps promise cost savings not only for people who switch from natural gas and oil furnaces, but for those switching from electric baseboards, because they will use far less electricity to produce the same amount of heat.

The Corporate Knights research division calculated that for a typical single-family detached house in Nova Scotia, switching from an oil furnace to a heat pump would save $1,750 in annual heating costs. They would save even more switching from baseboard heating: $2,773 per year.

The price to install a heat pump can vary from around $4,500 for a hybrid (one that works with your existing furnace) to upwards of $20,000 for a top-of-the-line centrally ducted model. Federal government rebates of up to $5,000 and zero-interest loans of $40,000, both offered through Ottawa’s Greener Homes Initiative, can significantly reduce how much you pay out of pocket at the outset. It can even eliminate the cost: if you’re switching from oil to a heat pump, there’s a special federal program that will cover up to $10,000.

Provincial rebates stack on top of the federal ones, offering an additional $5,000 in Ontario and Nova Scotia and up to $20,000 in Quebec, reducing upfront costs even further.

Since the federal subsidies were introduced in 2021, heat pump adoption has shot up, surpassing sales of natural gas furnaces in Canada for the first time, according to wholesale shipment information tracked by the Heating, Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Institute of Canada.

Because of their efficiency, heat pumps use far less energy to heat than furnaces, but just how big their impact is on carbon emissions is mostly determined by how the electricity is generated. In Nova Scotia, where the majority of electricity comes from coal and oil, switching from an oil furnace to a heat pump will reduce a typical household’s emissions by 1.2 tonnes. In provinces with lots of carbon-free renewable electricity, the greenhouse gas reductions are even greater. In Ontario, for example, a household making the switch to a heat pump would reduce their emissions by 4.2 tonnes and save $489 a year at today’s gas prices – savings that will nearly double by 2030 as the carbon price increases.

Canada-wide, if everyone switched to heat pumps, it would produce annual savings of $13.5 billion and emission reductions of 26.3 megatonnes, equal to 4% of Canada’s total GHG emissions, according to the Corporate Knights analysis.

For a peek at the future, look no further than Sweden, where heat pumps have almost entirely replaced oil for residential heat. Since 1990, heat pumps have been responsible for reducing carbon emissions from heating by 95%, according to Martin Forsén, the president of the European Heat Pump Association, who gave a recent presentation in Toronto. The adoption of heat pumps has gone so well in his Scandinavian country that he sees their global dominance as an inevitability. “I don’t think it’s a question of if. It’s just a question of when,” he says.

That’s a sentiment Gifford shares. Heating by burning fossil fuels in your basement will soon be a thing of the past. “It’s a necessary change and I’m looking forward to it,” he says. “It can’t happen soon enough.”

Savings from switching to an electric water heater and induction stove

Anya Barkan’s water heater was 15 years old and “a piece of garbage” when she called her rental company and asked for it to be replaced. After some back and forth that left her frustrated, she decided to break free from the rental contract she had inherited when she bought her home and get a heat-pump water heater. “It just made sense. We wanted to stop that monthly fee and get something that is much more energy-efficient and also not reliant on natural gas,” she says.

Breaking the contract proved much harder than getting the heat-pump water heater. But ever since, Barkan says, she has been happy – and not only because she no longer pays the monthly rental fee. “It’s like shooting two birds with one stone. It’s not just one thing or the other. You can make your house more efficient and lower your bills. But also, it’s better for the environment in terms of fighting climate change.”

Water heaters don’t have a huge impact on gas bills on their own. But like gas stoves, they are often one of the few links to the natural gas system in a home. If swapping these two gas appliances for electric means being able to cut your gas line, it supercharges the savings because it eliminates the fixed monthly charge for natural gas, which comes to $325 a year in Ontario.

The Corporate Knights research found that swapping out the gas water heater for one that operates with a heat pump would save an Ontario family $124 per year. Similarly for an induction stove: the annual savings in Ontario for switching from a gas stove are only $5, but if switching allows you to cut your gas line, those combined savings jump to $454 a year.

But it’s not just economics. There are other reasons people are looking to get rid of their gas stoves. Worries about air quality in the home surfaced earlier this year after an official with the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission said the agency was considering banning new gas stoves amid research that links them to childhood asthma.

While the ensuing uproar prompted the head of the agency to walk back talk of a ban, the health hazards are real. Health Canada’s residential indoor air-quality guidelines estimate that 25% of houses with gas stoves exceed the exposure limit for nitrogen dioxide, one of the toxic compounds released when a gas stove is turned on and “for brief periods of time after cooking,” even with “moderate ventilation.”

Meanwhile, some professional chefs recommend switching to induction stoves for performance reasons alone, saying they’re faster to heat up, more responsive, not as hot to work over and easier to clean.

Soon, people moving into new houses and apartments could have no choice but to go without gas appliances. Dozens of cities across the United States, recently joined by Vancouver, have banned natural gas hookups in new developments. New York State just passed a similar ban statewide, and Toronto and Montreal city councils are considering similar measures.

Even though they burn little gas, the climate impact of eliminating these gas-burning appliances isn’t negligible. Switching from a gas stove to induction will reduce an average Ontario household’s indoor emissions of greenhouse gas by 370 kilograms. Swapping a gas water heater for a heat pump version saves 640 kilos.

If everyone in Canada made these changes, the collective impact would reduce emissions by 7.6 megatonnes, more than 1% of all emissions in the country. It’s what analysts refer to as the light-bulb effect. When incandescent light bulbs were replaced by LEDs, the difference in electricity consumption was tiny for a lamp or light fixture. But multiplied across households, apartment buildings, university campuses and sport stadiums, the cumulative impact was enormous.

That’s where we’re at right now with climate change. The solutions are all readily available. The wind turbines and solar panels that will provide clean electricity are being adopted much faster than anyone predicted. Now it’s time to electrify and use that clean electricity to eliminate carbon emissions.

“It’s not just your individual action that will change the world,” says Barkan. “We need to go at it together.”

Full calculator

Calculate the cumulative impact of swapping out all four technologies below.

*To learn more about how averages were calculated, see our notes on assumptions and emission factors.

Marco Chown Oved, climate reporter, Toronto Star

Ralph Torrie, research director, Corporate Knights

Cameron Tulk, lead digital designer, Toronto Star

McKenna Deighton, digital designer, Toronto Star

Jack Dylan, creative director, Corporate Knights magazine